Grenfell: Value Engineering isn’t actually a play. It’s an edited version of the testimony heard by the Grenfell Tower Inquiry, particularly Phase 2, from January 2020 to July 2021. Along with director/producer Nicolas Kent, Richard Norton-Taylor has distilled the Inquiry’s proceedings into two-and-three-quarter hours of devastation. They show that tens, maybe even hundreds of people are responsible for the fire that killed 72 and injured almost as many. It’s verbatim theatre, but it leaves you speechless.

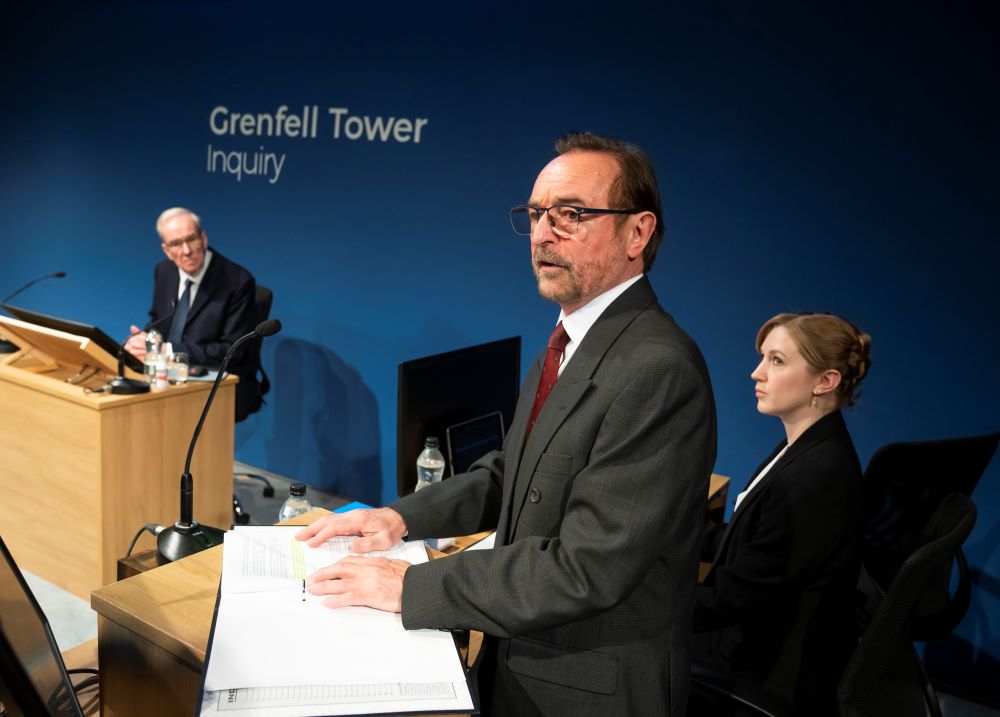

The set-up is simple. Designers Miki Jabikowska and Matt Eagland have recreated the room the hearings took place in pretty much perfectly to the untrained eye: three nondescript desks of light wood, microphones, a blue background reading "Grenfell Tower Inquiry". Documents flash up on screens, including a damning flowchart that shows how the different parties involved in the Tower’s construction all failed to meet fire regulations. It feels like we’re witnessing the Inquiry as it happened. At times, it’s painful to watch, and rightly so.  Some of the participants, like the contractor appointed to refurbish the Tower (Phill Langhorne), seem nonplussed to be told that their actions killed people. One of the first firefighters at the scene (Daniel Betts) breaks down during his testimony. Richard Millett QC (Ron Cook, pictured above) asks him if he alerted anybody inside the other flats on his way up to try and save a 13-year-old boy trapped on the 18th floor. He says that he did not; later, we find out that one of the residents banged on all the doors he could reach as soon as he knew that the building was on fire.

Some of the participants, like the contractor appointed to refurbish the Tower (Phill Langhorne), seem nonplussed to be told that their actions killed people. One of the first firefighters at the scene (Daniel Betts) breaks down during his testimony. Richard Millett QC (Ron Cook, pictured above) asks him if he alerted anybody inside the other flats on his way up to try and save a 13-year-old boy trapped on the 18th floor. He says that he did not; later, we find out that one of the residents banged on all the doors he could reach as soon as he knew that the building was on fire.

That kind of showing-not-telling is difficult to achieve with verbatim theatre, even for old hands like Kent and Norton-Taylor, who have been doing this since 1999, specialising in inquiries from the murder of Stephen Lawrence to the events of Bloody Sunday. “I invited the core participants not to indulge in a merry-go-round of buck-passing,” says Millett at the beginning of Act Two. “Regrettably, that invitation has not been accepted.” It’s a great line, and Cook delivers it with just the right amount of suppressed rage. But Norton-Taylor should have left it until after we’d had a chance to see the buck-passing for ourselves.  My other misgiving is how Norton-Taylor has approached race, which was and is a much bigger part of the tragedy than the editing makes it out to be. Derek Elroy (pictured right) is the only person of colour in the cast, playing Leslie Thomas QC; a stark contrast with both the victims of the fire, 85% BAME, and the Inquiry itself, whose members were 46% BAME. Elroy’s Thomas is masterfully composed as he describes how race is the “elephant in the room”, “inextricably linked” with the fire. Listening to him, you feel that the whole sequence of events simply wouldn’t have happened if the tower block were 85% white.

My other misgiving is how Norton-Taylor has approached race, which was and is a much bigger part of the tragedy than the editing makes it out to be. Derek Elroy (pictured right) is the only person of colour in the cast, playing Leslie Thomas QC; a stark contrast with both the victims of the fire, 85% BAME, and the Inquiry itself, whose members were 46% BAME. Elroy’s Thomas is masterfully composed as he describes how race is the “elephant in the room”, “inextricably linked” with the fire. Listening to him, you feel that the whole sequence of events simply wouldn’t have happened if the tower block were 85% white.

The crowd at the Tabernacle – about as diverse as the Inquiry – are absorbed from the get-go, reacting with scorn to the interviewees’ ever-more elaborate attempts to shift the blame. They claim they didn’t know that the material they all helped to wrap the Tower in was highly flammable; that the building regulations are confusing and difficult to read; that somebody else should have noticed. You half-expect them to say that somebody should have hit them over the head with a hammer labelled THIS BUILDING IS UNSAFE. “I’m not the fire consultant,” says the architect who designed the Tower’s refurbishment. “We’re not fire experts,” says the director of the specialist cladding firm. The word "hindsight" keeps cropping up, as if nobody could be expected to have any foresight.

"Value engineering" is a euphemism for cutting corners to save money. But Norton-Taylor shows us another meaning: how the values of management, local government and society itself have been engineered over the past 20 years to create the ideal conditions for the Grenfell fire. As in An Inspector Calls, nearly everyone is guilty.

“Please be sensitive,” one of the interviewees asks of Millett as he’s about to question her. Cook leaves a telling pause for us all to consider the implications of her request in the face of the tragedy she helped to make.

Add comment