To watch Deep Azure is to feel a double loss. The death of Prince Jones, the black student who was shot dead by a police officer in a case of mistaken identity, and the death of his friend, Chadwick Boseman, who wrote the play to commemorate him. Boseman, of course, would become world-famous as Marvel’s first black superhero, Black Panther’s King T’Challa, before dying of colon cancer aged 43. Yet the exuberance, inventiveness and giddy lyricism on display in this piece of hip-hop theatre – written by Boseman in his late twenties – is so bracingly original, it makes you grieve to wonder what kind of writer he might have become had he lived for longer.

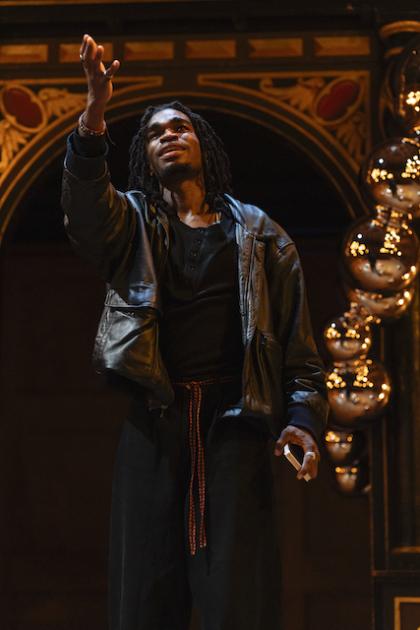

Sure, it’s messy, unruly and a bit all over the place. But even when you’re not certain what’s happening in Tristan Fynn-Aiduenu’s production, you’re enjoying both the visual and sonic invention. It begins with a beatboxing chorus dressed in silver retro space-age suits, singing about Joshua – known here as Deep (Jayden Elijah, also pictured below) – the prince who “left us too soon and returned to God”. There are strong echoes of Hamlet, as, watched by Deep’s ghost, the cast goes over the circumstances surrounding his death, asking questions about who really was to blame.

Interestingly, the emotional core of the production derives from Selina Jones’ extraordinary performance as Azure, Deep’s girlfriend, simultaneously crippled by grief and by paranoia about her weight. One of the striking aspects of the script is that, despite its tragic details, so much is suffused with a redemptive joy. Yet Jones dives deep into the abyss of pain, utterly unable to come to terms with the loss of the man she loved. “Is it a sin to lust after a ghost?” she asks at one point, her voice dark with emotion.

Prince Jones died in 2000. Since then, fatalities resulting from police action in the US have risen year on year, with the situation compounded by the shocking number of deaths connected to ICE under Trump. It would be all too easy to create a production awash with anger. Yet Boseman’s humane vision allows us to see all the characters’ faults and virtues, whether it’s Deep himself, “complicated to the point of confusion”, the revenge-driven Roshad (Justice Ritchie), or Elijah Cooke’s deceptively reassuring Tone, a friend whose support for Azure is fraught with more questionable agendas.

Though the music provides as much distraction as it does enlightenment, co-composers and rehearsal musical directors John Pfumojena and Conrad Murray deserve plaudits for a score that references everything from gospel to Samuel Barber’s Adagio. Tanaka Bingwa’s movement direction injects as much humour as it does tension. Full use is made of the Sam Wanamaker space, which characters popping up from the trap door below the stage, swinging from the pillars, running round the outside of the auditorium or serenading us from the musicians’ gallery.

You do wonder what this extremely unusual piece could have been like with a strong edit. All those big ideas, all those big emotions, that fantastically lyrical grasp of language – could this have been shaped into a truly effective drama? Or did it simply contain the seeds of a better work, that would have finally seen the light of day once Boseman had lived a bit more? You emerge from the theatre feeling overwhelmed by all the what-might-have-beens.

This is a tragedy, no mistake, on several levels. Ultimately the play is destined to be more curiosity than classic, yet it’s worth a visit if you’re intrigued by Boseman and was manifestly a unique, life-affirming talent.

Add comment