From seat 17 of Row 8, Block M35, Stair 14, Level 4, in a gathering of 75,000 spectators, almost all of them Welsh, it’s difficult to argue with the idea that Wales already has a national theatre. It’s called the Millennium Stadium (picture below). Just before kick-off yesterday afternoon, from my high-altitude perch, I looked across to the distant tunnel opposite. Its jaws belched fire and smoke and, in due course, a pumped-up team in red shirts. Their entry was greeted by a dozen gas-powered jet flames dotted around the touchline, spurting up towards the stadium roof. And then all those larynxes opened up for “Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau”. Oh yes, they know all about theatre in Wales.

Yesterday afternoon the country’s rugby team attempted, yet again, to end the drought of droughts. They have not beaten the All Blacks since the year of the Queen’s coronation, the year Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary (another triumphant Kiwi) “knocked the bastard off”. The Welsh travel to these encounters in hope, never expectation. In a country where every other soft rolling hill is charmingly promoted to the status of mountain, beating the Blacks is a Welsh kind of Everest. One day the peak will be scaled. One day. In the mean time, the only option is patience.

Yesterday afternoon the country’s rugby team attempted, yet again, to end the drought of droughts. They have not beaten the All Blacks since the year of the Queen’s coronation, the year Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary (another triumphant Kiwi) “knocked the bastard off”. The Welsh travel to these encounters in hope, never expectation. In a country where every other soft rolling hill is charmingly promoted to the status of mountain, beating the Blacks is a Welsh kind of Everest. One day the peak will be scaled. One day. In the mean time, the only option is patience.

However long the wait has been, the wait for a National Theatre of Wales has been longer. As far back as the autumn of 1944, Nigel Heseltine wrote in Wales, a periodical for Welsh intellectuals, that “the Welsh national theatre has been in cold storage too long... Those of us who want this theatre must define our terms... If enough of us want a theatre in Wales, we can have it.”

Not enough Welshmen wanted it enough. So for years the call has gone up, and for years it has not been answered. It never helped that London preferred to stay out of it. In 1969, the year of the Prince of Wales’s investiture, a question about government assistance was asked in the House, and batted away by Alice Bacon, the (Labour) minister for Education and Science. “I should think that Wales would want to initiate this,” she said, “rather than leave it to the Government.”

The issue festered for further decades. Various proposals were tabled and ignored. Then came devolution in 1997, and the project of building a new national confidence through institutions gained traction. Welsh politicians moved into the Welsh Assembly, the Welsh rugby team into the Millennium Stadium, and the Welsh National Opera into the Wales Millennium Centre. And finally last week National Theatre Wales (NTW) opened for business in an office above a small shop.

The premises are in one of those lovely old-fashioned covered arcades that decorate the capital, and keep its shoppers dry. The premises are hardly commensurate with anyone’s image of a National Theatre – those grandiloquent buildings in London and Dublin, in Prague and Beijing. But they are in keeping with the idea behind an organisation which aims to remain as light on its feet as a dinking, dancing Welsh wing three-quarter. But more of that later.

Heseltine’s call to arms, by no means the first mention of a Welsh national theatre, was made 65 years ago. Why has it all taken so very long? It depends on who you ask. Phil George, a former head of arts, music and features at BBC Wales, is the NTW’s inaugural chairman. “Wales is a complicated country,” he tells me, “and it doesn’t have the urban structure of Scotland or the impresario traditions of Manchester. The Abbey in Dublin was central to defining the Irish nation. Wales is a country of communities. That’s its great glory.” Dispersed communities don’t always have the means or the will to cohere, especially when there’s a highly politicised linguistic issue to pull focus. (The curtain went up on Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru, the Welsh-language NT, in 2005.)

And then there is the north-south divide. In 2004 the Boyden Report made its recommendations for a national drama strategy. In the ripe paraphrase of Professor Dai Smith (picture left), chair of the Arts Council of Wales, it concluded that “you guys are like ferrets in a sack quarrelling: you’ll never get your act together.” The ferrets in this instance were the competing theatres. There was never any consensus about where a national theatre might make its home. Seen from the other end of the telescope by London-based critics, it is Clwyd Theatr Cymru in Mold - run by former RSC artistic director Terry Hands – that has always been the most visible producing house in Wales. But Mold is tiny. And two thirds of the Welsh population lives down south. “We’ve been waiting for a new concept,” explains the director Mike Pearson, “because the squabble was always about one building or one company against another, and which one should have this badge of ‘national’.”

And then there is the north-south divide. In 2004 the Boyden Report made its recommendations for a national drama strategy. In the ripe paraphrase of Professor Dai Smith (picture left), chair of the Arts Council of Wales, it concluded that “you guys are like ferrets in a sack quarrelling: you’ll never get your act together.” The ferrets in this instance were the competing theatres. There was never any consensus about where a national theatre might make its home. Seen from the other end of the telescope by London-based critics, it is Clwyd Theatr Cymru in Mold - run by former RSC artistic director Terry Hands – that has always been the most visible producing house in Wales. But Mold is tiny. And two thirds of the Welsh population lives down south. “We’ve been waiting for a new concept,” explains the director Mike Pearson, “because the squabble was always about one building or one company against another, and which one should have this badge of ‘national’.”

Boyden recommended a preparatory phase in which a producer worked on developing a unified theatre ecology. Smith, who is as Welsh as can be, author of histories of the Welsh Rugby Union and the South Wales miners (and the learned source of the Heseltine article quoted above), could see that further talking was not the requirement. “I thought, ‘Brilliantly written report, and yet again we’re not going to get anywhere.” So he went to the Ministry for Culture - now Heritage - and lobbied for enough funding to pacify those regional theatres who feared a national theatre would absorb all the Arts Council’s largesse. And the Arts Council managed to secure a separate pot for NTW.

The result is that Wales is the only British nation to have increased its arts funding during the era of the credit crunch. For the first three years of its life, National Theatre Wales has been given £3 million. Having already spent some of that time and money on development, on Thursday above the shop in Castle Arcade it laid its plans before the media - as well as anyone tuning in to its webcast. And what delightful plans they are, full of ambition and surprise, awareness and wit.

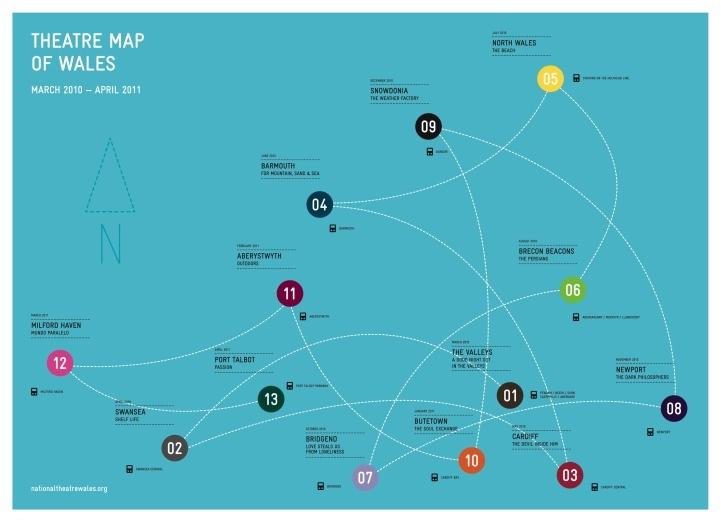

The concept is simple. All of Wales is a stage. Like its Scottish counterpart, which was launched in 2006, NTW will have no home. (For the record, Pearson assures me that the notion of theatrical homelessness, mooted in the late 1980s, was originally Welsh rather than Scottish.) The programme intends to draw what they are calling a “Theatre Map of Wales”. From Caernarfon to Newport, from Milford Haven to Sennybridge, the first year and a bit will yield 13 productions distributed across the country.

Wales is a much more sophisticated and complex society than the bloody English have ever understood

This is partly a matter of pragmatism. There’s no money to build a theatre. But there’s no reason either. The disparate nature of Welsh topography will be reflected in the stages the National Theatre visits. Yes, they’ll go to some regular theatres. A Good Night Out in the Valleys, the inaugural production next March, opens at the traditional proscenium of the Blackwood Miners' Institute, and tours through similar halls across the old mining towns of the Valleys. In May, Cardiff’s New Theatre will play host to a lost play written by John Osborne at 18. Osborne spent formative years in Wales, and set The Devil Inside Him, enigmatically, in a village 40 miles outside Swansea (which means it could be anywhere from Abergavenny to Aberaeron to Haverfordwest). It has never been performed uncensored. Indeed the play was so deeply buried in the Lord Chancellor’s bottom drawer that John Heilpern was apprised of its existence only after the publication of his 2006 Osborne biography.

For the rest of the year, the NTW will be like modern strolling players, putting on the show here or there. Among their found spaces are the disused reading room of the beautiful Old Library in Swansea and the charismatic Coal Exchange in Butetown, Cardiff's old docks. The artist Marc Rees will mount an installation piece about local history in a pound shop in Barmouth which was once a Nonconformist chapel. “It’s nothing new,” he explains of working in an unusual venue. “The tradition is we’ve always done things in vestries and chapels.”

Sometimes NTW won’t even be indoors. The Beach will be produced on the windy strands of the North Wales coast (such as Rhyl, picture right). A new version of Aeschylus’s The Persians, the first war play, will be performed on an MoD-owned ghost village used for miltary training in the Brecon Beacons. Audiences will be brought in on troop trucks.

Sometimes NTW won’t even be indoors. The Beach will be produced on the windy strands of the North Wales coast (such as Rhyl, picture right). A new version of Aeschylus’s The Persians, the first war play, will be performed on an MoD-owned ghost village used for miltary training in the Brecon Beacons. Audiences will be brought in on troop trucks.

But of all the open-air shows, the eye-catcher is a revival in 2011 of an Easter tradition in Port Talbot: a promenade version of The Passion. The town is famous for producing steel and actors. Richard Burton and Anthony Hopkins grew up there, and so did Michael Sheen. Nowadays resident in Los Angeles, Sheen will return to direct and act in a new Passion Play written by the poet Owen Sheers. “I first saw the Passion Play in Margam Park when I was about 12,” Sheen says. “I saw it a few times over the years up until it stopped being done. It was a story I knew come to life in front of me. I saw the people of my town walking out of the forest and out of another time... I am both excited and terrified about this project. Which I suppose is the perfect state of mind to approach it in.”

On Friday morning I went for a walk in the pine-smothered hills/mountains between Maesteg and Port Talbot. In one direction the Black Mountain loomed. Out there somewhere in the mists hid Pen-y-Fan. And from the heights I could also look down to the coast where the chimney stacks of Port Talbot’s unlovely steel works thrust into the clouds. NTW really does plan to be a very broad church indeed. And they've managed to programme all these outdoor productions without booking a visit to a single castle or abbey ruin. One hopes there's some of that in the pipeline.

On Friday morning I went for a walk in the pine-smothered hills/mountains between Maesteg and Port Talbot. In one direction the Black Mountain loomed. Out there somewhere in the mists hid Pen-y-Fan. And from the heights I could also look down to the coast where the chimney stacks of Port Talbot’s unlovely steel works thrust into the clouds. NTW really does plan to be a very broad church indeed. And they've managed to programme all these outdoor productions without booking a visit to a single castle or abbey ruin. One hopes there's some of that in the pipeline.

While wandering across the country, productions will explore a breadth of theatrical styles. As well as Greek tragedy and medieval street theatre, there are new plays, devised plays, oral-history plays, exhumed plays, plays which will stretch the definition of play to the limit. Among the NTW’s collaborators are the WNO and, in their field, the equally esteemed NoFit State Circus, who are coming in from the big top to put on a show called Mundo Paralelo at the Torch Theatre in Milford Haven. There are plays about eternal Welsh verities – December brings to Galeri Caernarfon a Snowdon-inspired work called The Weather Factory – and about new Welsh anxieties: the Bridgend playwright Gary Owen is working on a play called Love Steals Us from Loneliness, suggested by the recent endemic of teenage suicides in his hometown. (It will be a partnership with Cardiff's new-writing theatre, Sherman Cymru.) This traumatic subject gave rise to the brightest moment at the launch. A Skype link to four members of the Bridgend Youth Theatre (picture below), all crammed onto a screen, reassured the assembled media that “Bridgend is a great place to live” and “We’re really happy!” It's safe to assume that Owen's play will not hold such a cheery mirror up to nature.

The presentation was fronted by the two people charged with bringing all this to fruition. The artistic director is John McGrath, whose ten years in charge of the nimble, site-hopping, out-reaching Contact Theatre in Manchester was deemed the perfect qualification. His surname didn’t seem to trouble the board. “I am genetically Irish,” he concedes, “but I was born in North Wales and spent the first five years of my life here. Like many a Scouser I spent all my holidays in North Wales. There’s definitely not been a case of people wanting me to prove a Welsh heritage, and when the board appointed me they didn't even know I’d been born in Wales. But when they found out they were quite delighted.”

The presentation was fronted by the two people charged with bringing all this to fruition. The artistic director is John McGrath, whose ten years in charge of the nimble, site-hopping, out-reaching Contact Theatre in Manchester was deemed the perfect qualification. His surname didn’t seem to trouble the board. “I am genetically Irish,” he concedes, “but I was born in North Wales and spent the first five years of my life here. Like many a Scouser I spent all my holidays in North Wales. There’s definitely not been a case of people wanting me to prove a Welsh heritage, and when the board appointed me they didn't even know I’d been born in Wales. But when they found out they were quite delighted.”

His producer is Lucy Davies (with McGrath in front of the Theatre Map of Wales, picture left), who spent two stints at the Donmar Warehouse, first as literary manager under Sam Mendes, then executive producer to Michael Grandage. For three years she also ran the National Theatre’s Studio. So she knows equally about the key tasks: developing new work and raising cash. And not that it should matter, but her name is known on the South Bank in London. “It would be fantastic if we did something together with the National Theatre,” she says when I ask if there are plans for collaboration. “All those conversations are there to be had. Inevitably we will become a punk little sister.”

One of the many reasons why NTW needs to exist is that the National Theatre of Great Britain, to give it its full name, has generally ignored the Welsh corner of the realm. There’s been the odd Peter Gill play, but the NT didn’t get round to staging the pre-eminent Welsh masterpiece, Under Milk Wood, until 1994. Which begs the question: when will the NTW be visiting Llareggub, the west Wales town of Dylan Thomas’s imagination? “We wanted to focus in this first year on giving new commissions to writers,” says McGrath. “Ideally we would like Peter Gill to write something for us. And I really want to do Under Milk Wood, but everyone else is telling me not to. I think it would have to be a truly extraordinary version of it.” Instead, at the Riverfront in Newport they are staging The Dark Philosophers, four stories written by his contemporary and namesake, the Valleys novelist Gwyn Thomas.

The Theatre Map of Wales will of course aim to look beyond the borders. There are already collaborations coming with McGrath’s old company Contact, and the Berlin experimentalists Rimini Protokoll in a show for Aberystwyth provisionally titled Outdoors. But the idea is to have the outsiders looking in and taking the measure of a new confident burgeoning Wales. Dai Smith is hopeful that the NTW's work will help to stamp out old ideas about the Principality. “We can get rid of the clichés that there’ll be dancing and singing in the Valleys tonight. NTW is going to have to examine the sentimentality and the nostalgia. But Wales is a much more sophisticated and complex society than the bloody English have ever understood.” Worrying what the bloody English think is of course a Welsh cliché in itself. National Theatre Wales can and must kick all that into touch.

If only it could do something about the Kiwis (performing the haka, picture left) On Thursday evening I left Castle Arcade and wandered along the street past Cardiff Castle. Above me fireworks peppered the skies. I guess they weren’t there to serenade the birth of a new national institution, but that’s how it felt. After all, in Wales there was nothing else to celebrate last week. On a corner I walked into a Welsh nemesis: a group of fit young hulks in black Adidas shirts. Strolling players of a different stripe, on Saturday afternoon the All Blacks rugby team duly acted out their latest victory in Wales’s other national theatre. Patience, patience. Good things come to those who wait.

If only it could do something about the Kiwis (performing the haka, picture left) On Thursday evening I left Castle Arcade and wandered along the street past Cardiff Castle. Above me fireworks peppered the skies. I guess they weren’t there to serenade the birth of a new national institution, but that’s how it felt. After all, in Wales there was nothing else to celebrate last week. On a corner I walked into a Welsh nemesis: a group of fit young hulks in black Adidas shirts. Strolling players of a different stripe, on Saturday afternoon the All Blacks rugby team duly acted out their latest victory in Wales’s other national theatre. Patience, patience. Good things come to those who wait.

- More information at the NTW website

Add comment