War Horse at the National Theatre on Sunday’s Armistice Day centenary: there were medalled veterans and at least one priest in the rows in front, dark suits and poppies all around, and scarcely a youngster in sight. When the bells rang out in a closing scene, the tolling was extended, and the veterans in the audience stood. Eleven years after the play-turned-phenomenon began its first run at the National, many of the original creative team were there for this return of the touring production. Sir Michael Morpurgo took the stage for an introduction. “It’s not the show that matters, it’s the people that the story’s about,” he told us. “That’s why I’m going to be sitting here watching tonight… It’s for you, but it’s also for them.”

For anyone not among the some seven million people in 11 countries who have seen the playwright Nick Stafford’s stage version, or the millions more who know the 2011 Steven Spielberg film, War Horse is based on Murpurgo’s children’s novel about the Devonshire boy Albert Narracott and his beloved horse, Joey. They grow up together, and after Joey is sold off as a cavalry horse at the start of World War I, Albert goes to France, with the dreamer’s goal of getting him back. The second major equine character is Topthorn, a magnificent black charger. The action, led by the horses, reaches the German lines and occupied France.  It is safe to say that from the beginning of a theatrical run that included five Tony Awards on Broadway in 2011, it has been the puppets, from South Africa’s Handspring company, and their choreography, that have stolen the show. In the cast list, the horses come first. One early thrill comes when the foal Joey gives way to the magnificent adult rearing up behind him, manned by three puppeteers. Equally, when these masterful puppeteers step away from the frame of a dying horse, it as if they are leaving like spirits. There’s an intimidating hand-carried WWI tank, and of course The Goose, played deliciously here by Billy Irving (pictured above). In my book this wheeled comical honker deserves a spin-off show all of his own (War Goose?).

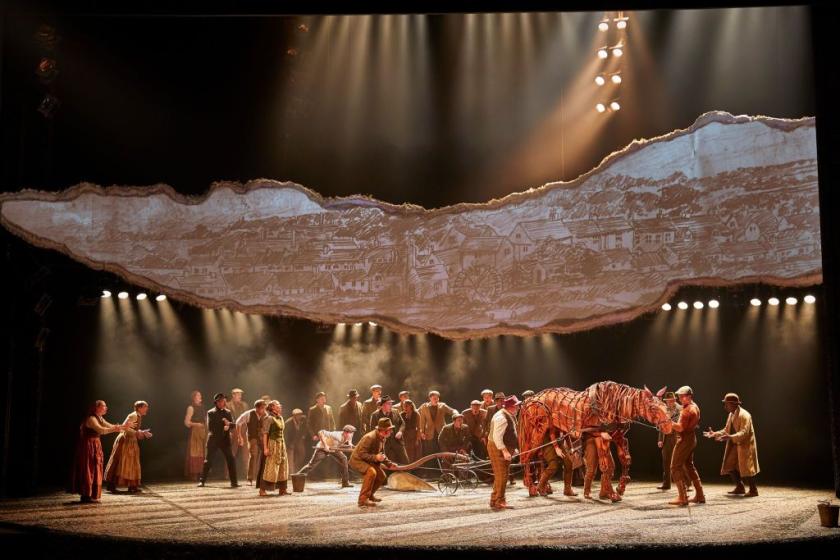

It is safe to say that from the beginning of a theatrical run that included five Tony Awards on Broadway in 2011, it has been the puppets, from South Africa’s Handspring company, and their choreography, that have stolen the show. In the cast list, the horses come first. One early thrill comes when the foal Joey gives way to the magnificent adult rearing up behind him, manned by three puppeteers. Equally, when these masterful puppeteers step away from the frame of a dying horse, it as if they are leaving like spirits. There’s an intimidating hand-carried WWI tank, and of course The Goose, played deliciously here by Billy Irving (pictured above). In my book this wheeled comical honker deserves a spin-off show all of his own (War Goose?).

War Horse is a bit of a franchise now, with its own range of merchandise. It started out in the Olivier, co-directed by Marianne Elliott and Tom Morris to utilise that auditorium’s drum revolve that rises out of the stage, and the play has returned this time to the Lyttelton with an adaptable set. The first version used original languages, with the Germans speaking German, now dropped in favour of an all-English script.

The characters and dialogue stitched around the impressive beasts are at times frustratingly mediocre. The early scenes, nominally set in the Devon countryside, have a pantomimic quality, as if we’re in the land of Jack and the Beanstalk. One looks for greater depth from young Albert (Thomas Dennis, pictured right), so as to deliver on his relationship with Joey, though the tear-jerking climax remains intact. It’s a different story with Peter Becker, as Friedrich Muller, the German officer and horseman; his bonding with the horses is mature and sure, and they acquire character in his company. Gwilym Lloyd shows wonderful physicality as Albert’s father Ted, both dissolute and ineffectual. Jason Furnival’s Sergeant Thunder is solid as a rock, while Jasper William Cartwright is touching as Billy Narracott, the callous casualty. Rae Smith’s poignant drawings, based on the idea of a wartime’s officer’s sketches, are projected overhead on a ragged stretch of white; they can also be seen in a display case outside.

I came to War Horse from my own simple highlight of the Armistice Day centenary: a talk at a local church from a veteran of Afghanistan - a Lieutenant Colonel and military doctor. In uniform, with full medals, he read his observational poem about a medical team receiving a triple amputee helicoptered in from the front, pumping his body full of blood as they fought to find a heartbeat. From there he talked of his current work with dementia patients, who tragically lose the assembly of memories – the remembrance – that makes us human.

To come to War Horse directly following felt like the very reverse of quiet reflection on the war to end all wars. The battlefront scenes are interrupted by frequent, brutal blasts of cacophonous sound and light, and one begins to dread them. On Remembrance Day, the scenes of the men in uniform, singing as they cross the Channel, had particular resonance. But when the horse Joey is snared in the barbed wire, in the midst of No Man’s Land, the animal’s cry becomes a cry for all.

Add comment