Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories review - 'in pictures you can let all your rage out' | reviews, news & interviews

Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories review - 'in pictures you can let all your rage out'

Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories review - 'in pictures you can let all your rage out'

The artist who talks freely about her marriage, but not the following 30 years

“My mother has always been a bit of a mystery to me not only as an artist but also as a mum,” declares Nick Willing by way of introduction to his film for BBC Two on the painter Paula Rego, who turned 82 in January. What follows is as far removed from a traditional biopic as you could hope to find.

There are no experts wittering on about Rego’s importance to contemporary British art or analysing the meaning of her strange, narrative pictures and the powerful women who inhabit them. There’s no bigging up of her career; you have to wait until the end to learn that in Portugal, where she was born, a museum dedicated to her vast output was built in Lisbon in 2009, that in 2010 she was made a Dame of the British Empire and at a Sotheby’s auction in 2015 her picture Looking Out, 1997 sold for £800,000.

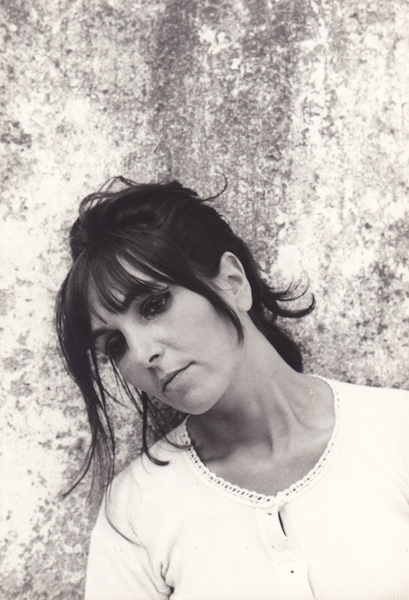

In place of pundits and plaudits, the film offers an intimate portrait. We are welcomed into the artist’s house and studio to watch her at work and answer her son’s questions about her life. He is especially interested in her marriage to the painter, Victor Willing, whom she met at the Slade, where she was a student from 1952. The family history is copiously illustrated with snapshots and home movies which show what a beauty Rego was; her film star good looks remind me of Juliette Greco (pictured right: Paula Rego in 1967 by Manuela Morais). Her work is well represented by shots of her most important pictures, while clips from previous interviews show her at her most animated.

In place of pundits and plaudits, the film offers an intimate portrait. We are welcomed into the artist’s house and studio to watch her at work and answer her son’s questions about her life. He is especially interested in her marriage to the painter, Victor Willing, whom she met at the Slade, where she was a student from 1952. The family history is copiously illustrated with snapshots and home movies which show what a beauty Rego was; her film star good looks remind me of Juliette Greco (pictured right: Paula Rego in 1967 by Manuela Morais). Her work is well represented by shots of her most important pictures, while clips from previous interviews show her at her most animated.

To be given such privileged access is especially rewarding since Rego is notoriously shy. Whenever I’ve interviewed her I’ve had to coax the words out; it was always worth the effort though, because when she did open up, she would offer colourful descriptions of the people in her pictures and their bizarre antics. Here she gives a more personal account of the way her paintings reflect aspects of her life.

A dramatic series showing young women enduring the pain and anguish of illicit abortions was made in response to the failure of the 1998 referendum in Portugal to legalise abortion. When shown in Lisbon, these harrowing images helped turn the tide of public opinion so that a subsequent referendum saw the vote go the other way and abortion was legalised. This is public knowledge, but in the film Rego reveals the extent to which the series also reflects her personal story. Like many Slade students, she got pregnant numerous times and had multiple abortions. When she finally refused to have another, Willing went back to his wife and she returned to Portugal to have the baby. Not long afterwards, though, he decided to join them and the couple married as soon as his divorce came through. They lived in a beautiful house in Ericeira that had belonged to Rego's grandparents, had two more children and only returned to London in 1974 after her father died and the family business collapsed.

She describes Portugal as a repressive society, especially for women. For instance, her grandmother had told her always to obey her husband no matter what he demanded, and she claims never to have stood up to Willing even when he was unfaithful. I have always been struck by the contrast between the demonic women and girls whom Rego paints and draws with such gusto and her apparently demure persona. Her son makes a similar observation. “It's interesting”, he says, “that there’s so much emotion and power and intensity in your pictures, yet in your personal life you’re quite quiet and private and closed.”

She describes Portugal as a repressive society, especially for women. For instance, her grandmother had told her always to obey her husband no matter what he demanded, and she claims never to have stood up to Willing even when he was unfaithful. I have always been struck by the contrast between the demonic women and girls whom Rego paints and draws with such gusto and her apparently demure persona. Her son makes a similar observation. “It's interesting”, he says, “that there’s so much emotion and power and intensity in your pictures, yet in your personal life you’re quite quiet and private and closed.”

“I’m shy,” Rego replies. “In my pictures I can do anything ... you are much more yourself... you can let all your rage out.” So her work is an outlet for the feelings she was brought up to repress; in pictures the underdog can wreak revenge. The women in her potent series of Dog Women, for instance, are clearly leading a dog’s life; they appear cowed, yet they snarl and snap and look set to attack their persecutors when the time is ripe.

Willing died in 1988 from the multiple sclerosis that had afflicted him for over twenty years. The Departure shows a young woman combing a man’s hair. He is wearing a smart suit and his trunk stands waiting in the foreground; he is being prepared for leave-taking as if he were already a corpse. It was Rego’s way of coping with her husband’s impending death. Later that year, the picture was exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery in a solo show which launched Rego’s career in this country. Since then, her work has gone from strength to strength and her international reputation has blossomed.

Willing died in 1988 from the multiple sclerosis that had afflicted him for over twenty years. The Departure shows a young woman combing a man’s hair. He is wearing a smart suit and his trunk stands waiting in the foreground; he is being prepared for leave-taking as if he were already a corpse. It was Rego’s way of coping with her husband’s impending death. Later that year, the picture was exhibited at the Serpentine Gallery in a solo show which launched Rego’s career in this country. Since then, her work has gone from strength to strength and her international reputation has blossomed.

My main quibble with Nick’s film is that by focusing on his parents' marriage, he gives the impression that Rego’s emotional life came to a standstill when her husband died and that she mainly finds solace in her work. “I’m married to my pictures”, she says, “drawing is an erotic activity”, but I don’t believe that she has had no significant relationships in the last 30 years, especially as she talks about the lover who supported her during the final period of Willing’s illness.

Consequently, the most successful decades of her artistic life are glossed over as if they mattered far less than her marriage. This portrayal of her as a lonely widow encourages one to see the array of props cluttering her studio as surrogates for actual friends and lovers when, in fact, they are crucial aspects of her work. Rego likes to draw either from real people – Lilia Nunes poses for most of her female characters (pictured above: Nunes helping Rego dress a model of a pregnant man) – or life-sized models; she is therefore surrounded by a huge collection of dolls and papier maché birds, animals, reptiles and a cast of the archetypal characters who inhabit the fairy stories that feed her vivid imagination and often appear in her work (pictured below).

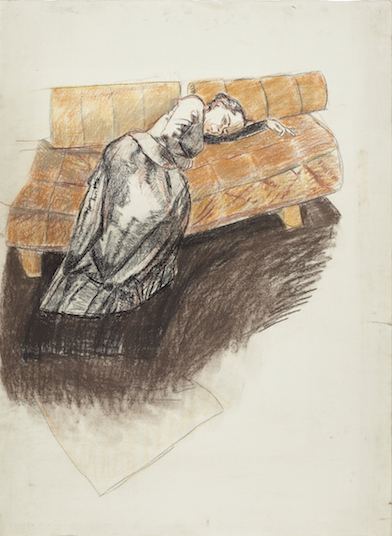

Rego has suffered from depression since childhood; in 2007 she recorded a particularly bad spell in a set of drawings of a lonely woman curled up in despair (pictured above left: Depression 2007). Because she was ashamed of being so low, she shut the drawings away in a plan chest, but the spirit of openness that prompted her to agree to this fascinating film also encouraged her to exhibit the drawings at the Marlborough Gallery.

Rego has suffered from depression since childhood; in 2007 she recorded a particularly bad spell in a set of drawings of a lonely woman curled up in despair (pictured above left: Depression 2007). Because she was ashamed of being so low, she shut the drawings away in a plan chest, but the spirit of openness that prompted her to agree to this fascinating film also encouraged her to exhibit the drawings at the Marlborough Gallery.

As a sequel to Nick Willing’s vivid portrait of Paula as wife, mother and artist, I would like a more traditional biopic that focuses on Paula Rego, the internationally famous artist whose career took off the year that her husband died.

- Paula Rego’s Depression Series is at Marlborough Fine Art until 1 April

- More TV reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment