Studio 17: The Lost Reggae Tapes, BBC Four review - a perfectly paced tale of world-shaking basslines and human frailty | reviews, news & interviews

Studio 17: The Lost Reggae Tapes, BBC Four review - a perfectly paced tale of world-shaking basslines and human frailty

Studio 17: The Lost Reggae Tapes, BBC Four review - a perfectly paced tale of world-shaking basslines and human frailty

The inside story of the evolution of reggae and the family that helped facilitate it

If there was ever a documentary that needed you to have good speakers on your TV setup – or good headphones if you're watching on computer or tablet – this is it.

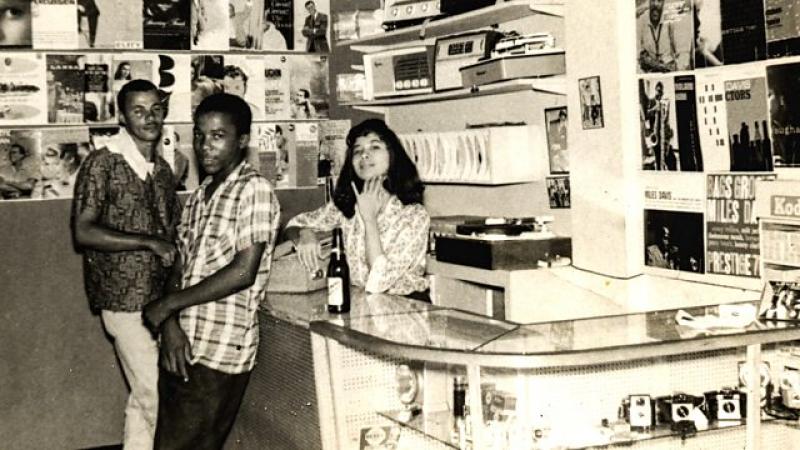

The story is, in some ways, simple. In the late 1950s Chinese-Jamaicans Vincent “Randy” Chin and his new wife Patricia started selling records for jukeboxes across the islands. They started a sideline in selling the old used records from a cart, then a store in downtown Kingston, which became successful enough to build a studio upstairs. The synergy between the two – the store in which Vincent and “Miss Pat” could gauge what was popular and even test out new releases, and the studio which had all the hottest musicians in mento, then ska, then reggae and dub hanging around the pavement outside in the hope of being picked for a session – was perfect, and Randy's Records aka Studio 17 became a hub for the explosion through the Sixties and Seventies of Jamaican music worldwide, with the Chins' oldest son Clive as a studio engineer under the tutelage of the great Errol Thompson.

The Chins moved to New York in the Eighties, driven away by the factional street violence of Kingston – but continued their involvement in reggae, forming the giant VP (Vincent & Pat) label and championing the new digital sounds of dancehall. Vincent died in 2007, but Miss Pat has continued at the helm of VP into her 80s. This film told this story, but halfway through it became the story of the archive of studio tapes that were left behind in the move to NYC. These were thought lost after the shuttered studio was flooded and looted following Hurricane Gilbert in 1988 – but incredibly in 2001, Clive found them and rescued them. For unexplained reasons, he never did anything with them, despite Joel's urging – but when Joel was murdered in Jamaica in 2011, he was driven to restore and digitise them. The second half of the film, then, became less history lesson and more family drama as the fate and ownership of the recordings was discussed.

The mastery here was that from the Fifties to the present day, the narrative just flowed along on those endless basslines, borne by that natural Jamaican way with a story. Along the way, major incidents of political turmoil and street violence cropped up as the backdrop to the story, and personal and artistic victories and tragedies came thick and fast, but none of this was presented as high drama. There were practically no grand revelations, no shock twists, just life being lived as some of the greatest music of the modern age was being made.

And it really is the greatest, as the calibre of talking heads in the film should suggest: Jimmy Cliff, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Sly Dunbar, Ernest Ranglin, Bunny Lee, King Jammy, the late Rico Rodriguez all provide vital memories, while the philosophical sorrow of Clive and the spark and steel of the remarkable Miss Pat provide the centre of the narrative. There was really nothing to fault here: it was the story of one of the most important musical connecting points of the modern world, the archive footage (including from fictionalised versions of Randy's in The Harder They Come and Rockers) outstanding, the sense of the small human stories that make up history constantly palpable, and for 85 minutes the pace was near perfect. Even if you're not a reggae lover, there was a lot to love here, but if you are, it's a treasure trove.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

theartsdesk Q&A: writer and actor Mark Gatiss on 'Bookish'

The multi-talented performer ponders storytelling, crime and retiring to run a bookshop

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Ballard, Prime Video review - there's something rotten in the LAPD

Persuasive dramatisation of Michael Connelly's female detective

Bookish, U&Alibi review - sleuthing and skulduggery in a bomb-battered London

Mark Gatiss's crime drama mixes period atmosphere with crafty clues

Bookish, U&Alibi review - sleuthing and skulduggery in a bomb-battered London

Mark Gatiss's crime drama mixes period atmosphere with crafty clues

Too Much, Netflix - a romcom that's oversexed, and over here

Lena Dunham's new series presents an England it's often hard to recognise

Too Much, Netflix - a romcom that's oversexed, and over here

Lena Dunham's new series presents an England it's often hard to recognise

Insomnia, Channel 5 review - a chronicle of deaths foretold

Sarah Pinborough's psychological thriller is cluttered but compelling

Insomnia, Channel 5 review - a chronicle of deaths foretold

Sarah Pinborough's psychological thriller is cluttered but compelling

Live Aid at 40: When Rock'n'Roll Took on the World, BBC Two review - how Bob Geldof led pop's battle against Ethiopian famine

When wackily-dressed pop stars banded together to give a little help to the helpless

Live Aid at 40: When Rock'n'Roll Took on the World, BBC Two review - how Bob Geldof led pop's battle against Ethiopian famine

When wackily-dressed pop stars banded together to give a little help to the helpless

Hill, Sky Documentaries review - how Damon Hill battled his demons

Alex Holmes's film is both documentary and psychological portrait

Hill, Sky Documentaries review - how Damon Hill battled his demons

Alex Holmes's film is both documentary and psychological portrait

Outrageous, U&Drama review - skilfully-executed depiction of the notorious Mitford sisters

A crack cast, clever script and smart direction serve this story well

Outrageous, U&Drama review - skilfully-executed depiction of the notorious Mitford sisters

A crack cast, clever script and smart direction serve this story well

Prost, BBC 4 review - life and times of the driver they called 'The Professor'

Alain Prost liked being world champion so much he did it four times

Prost, BBC 4 review - life and times of the driver they called 'The Professor'

Alain Prost liked being world champion so much he did it four times

The Buccaneers, Apple TV+, Season 2 review - American adventuresses run riot in Cornwall

Second helping of frothy Edith Wharton adaptation

The Buccaneers, Apple TV+, Season 2 review - American adventuresses run riot in Cornwall

Second helping of frothy Edith Wharton adaptation

The Gold, Series 2, BBC One review - back on the trail of the Brink's-Mat bandits

Following the money to the Isle of Man, Spain and the Caribbean

The Gold, Series 2, BBC One review - back on the trail of the Brink's-Mat bandits

Following the money to the Isle of Man, Spain and the Caribbean

Dept. Q, Netflix review - Danish crime thriller finds a new home in Edinburgh

Matthew Goode stars as antisocial detective Carl Morck

Dept. Q, Netflix review - Danish crime thriller finds a new home in Edinburgh

Matthew Goode stars as antisocial detective Carl Morck

Comments

The only downside was that

I wondered about this too but

Brilliant and emotional.