It's impossible to overstate the reverence accorded the painter Agnes Martin by her fellow artists; in the panoply of American cultural goddesses, she is right up there with Emily Dickinson. Yet she is scarcely known in the wider world, partly because her work is relentlessly abstract, but also because she was deliberately evasive.

She left New York in 1967 just as her reputation was gaining momentum and moved to New Mexico, where she lived as a recluse until her death in 2004. She rarely agreed to interviews and when she did speak would give conflicting accounts of her past, so there was no reliable back story to attract media attention.

Tate Modern’s superb survey may not turn Martin into a household name, but it provides an invaluable opportunity to discover what makes her ravishingly beautiful work so satisfying; the balance – perfectly poised – between conceptual clarity and sensuousness.

Tate Modern’s superb survey may not turn Martin into a household name, but it provides an invaluable opportunity to discover what makes her ravishingly beautiful work so satisfying; the balance – perfectly poised – between conceptual clarity and sensuousness.

Mentors rarely live up to their promise, so seeing a full retrospective of an artist you once tried, in vain, to emulate is a risky business. I feared disappointment at every turn, but I needn’t have worried; Martin never falters. She was after perfection and ruthlessly edited out anything she considered a failure. She continued working to the end (she was 92 when she died) and her last request was for her dealer, Arne Glimcher, to destroy the two unfinished paintings lying on the floor of her studio.

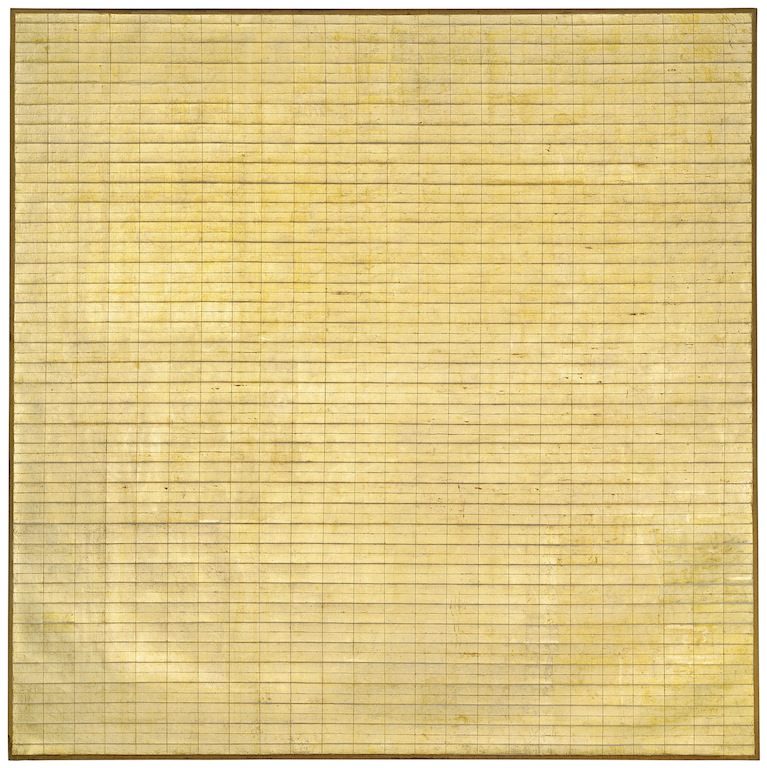

What makes Agnes Martin’s paintings so special, then? She was nearly 50 when she adopted the grid pattern that was to become her signature style, with paintings measuring 6ft square. Such rigorous geometry could have led to mind-numbing repetition, but in place of simplicity and sameness, Martin created subtlety, contrast and complexity.

Take Friendship, 1963, for instance (pictured above right) . The canvas is covered in a layer of gold leaf uniformly incised with vertical and horizontal lines. The contrast between the warm glow of the gold and the cool uniformity of the grid creates a delicious balance between intellect and feeling, head and heart. The juxtaposition could have seemed glib – perfection, after all, is more desirable as a concept than an actuality – were it not for the slight bruising that, in places, discolours the gold with smudges of blood red. The careful measurements and calculations that underpin each composition lend the work a satisfying sense of order and stability. No attempt has been made to hide the pencil lines and markings delineating each grid; in many cases, they are all there is and the mood or feeling of the work arises entirely from the way they articulate the space and interact with the greyish layer of gesso beneath.

The careful measurements and calculations that underpin each composition lend the work a satisfying sense of order and stability. No attempt has been made to hide the pencil lines and markings delineating each grid; in many cases, they are all there is and the mood or feeling of the work arises entirely from the way they articulate the space and interact with the greyish layer of gesso beneath.

More often, though, translucent washes of pale red, blue or yellow paint are brushed on with unabashed spontaneity. Like clouds scudding across the sky or wind agitating the leaves, they infuse the images with nervous energy and pulsating life. The dialogue this establishes between order and evanescence introduces a philosophical dimension to the work that reflects Martin’s interest in Zen Buddhism and Taoist philosophy.

But there is also a powerful psychological dimension. In 1961, Martin was found wandering around New York in a catatonic state and was diagnosed with schizophrenia. She spent most of the following year in hospital and, for the rest of her life, continued to suffer from bouts of mental illness. In paintings like A Grey Stone, 1963, she obsessively pins down the surface by placing a single brushmark inside each tiny cell of the grid. On the one hand, it feels like an attempt to describe entrapment while, on the other, it seems like a desperate bid to establish order and stability out of chaos.

In 1967 she sold all her possessions, bought a camper van and set off on a journey round the U.S and Canada (where she was born in 1912). Eighteen months later she settled in New Mexico (Agnes Martin pictured right; photo: Gianfranco Gorgoni, 1974) and built herself a modest adobe house. She didn’t start working again until 1972, when she was invited to produce a portfolio of 30 screen prints. On A Clear Day explores various permutations of the grid – lines close to or far apart, open ended or boxed in – alongside looser configurations of horizontals and verticals.

In 1967 she sold all her possessions, bought a camper van and set off on a journey round the U.S and Canada (where she was born in 1912). Eighteen months later she settled in New Mexico (Agnes Martin pictured right; photo: Gianfranco Gorgoni, 1974) and built herself a modest adobe house. She didn’t start working again until 1972, when she was invited to produce a portfolio of 30 screen prints. On A Clear Day explores various permutations of the grid – lines close to or far apart, open ended or boxed in – alongside looser configurations of horizontals and verticals.

Printed in a delicate grey line with no trace of the wobbles characterising the hand drawn originals, the images are calm and assertive. What could have been a boring exercise in graphic dexterity is, by turns, charming, playful, quixotic, obtuse or even wanton. Martin was aiming, it seems, to convey the tranquility that the clear light and wide open spaces of New Mexico had engendered in her. “If you can go with them”, she wrote, “and hold your mind as empty and tranquil as they are and recognize your feelings, at the same time you will realize your full response to this work.”

Her paintings may evoke a mood or conjure a feeling state, but they are far more than reflections of a state of mind. As I walked into Room 7 and encountered Untitled no 3, 1974, (main picture) I was overcome by an irrational surge of happiness. I wrote down “lucidity, clarity, restraint”, words that don’t come close to explaining why this configuration of pale pink and blue washes dissected by white lines induced a feeling of joy that took my breath away and left me grinning foolishly.

Part of the pleasure comes from the exquisite craftsmanship. The paintings may look fluent and easy, but detailed preparation is required to determine the thickness of the underlying gesso, the divisions of the square and the consistency of the paint. Loose and vigorous brushmarks produce a sense of swirling restlessness; elsewhere, thin washes of colour sweep freely over a smooth ground only to snag on the pencil lines, producing subtle modulations that make the surfaces pulsate, blush or shimmer (pictured above: Gratitude, 2001).

Part of the pleasure comes from the exquisite craftsmanship. The paintings may look fluent and easy, but detailed preparation is required to determine the thickness of the underlying gesso, the divisions of the square and the consistency of the paint. Loose and vigorous brushmarks produce a sense of swirling restlessness; elsewhere, thin washes of colour sweep freely over a smooth ground only to snag on the pencil lines, producing subtle modulations that make the surfaces pulsate, blush or shimmer (pictured above: Gratitude, 2001).

Martin believed in the power of art to offer transcendence and a sense of sublime peace emanates from The Islands, 1979 – a group of 12 paintings created as a single entity, which have been beautifully hung in a white room. Painted in limpid bands of white and oh, so pale blue, the canvases have an ineffable beauty that seems to offer release from the quotidian to another realm of perception and experience. I left the exhibition feeling as if I was walking on air.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment