In one of Dora Maar’s best known images, a fashion photograph from 1935 (pictured below), a woman wearing a backless, sparkly evening gown appears to be making her way backstage through a proscenium’s drapes. The star of the show exits the limelight, cheekily concealing her face behind a six-pointed star snatched, maybe, from the star-spangled scenery. Though she’s bracing herself against the wings her posture is also suggestive of abandon, the kind of arms-up relief that comes with finishing a race or dancing late at night when no-one cares. She flirts with the lens and the lens flirts back, her provocation inviting a response.

Maar’s women, as they turn away, threaten to slip out of sight. But where some are playful, for others the caught turn can pivot on disturbance. Repulsing attention, such a turn can suggest a self-effacement that could be as much an expression of creativity as destruction. In an untitled print from 1938, a nude, possibly Maar herself, sits with her back to the camera. Her posture is elegantly composed for the frame but the negative itself has been altered. Water or chemicals have been poured on top so that the celluloid has buckled, the emulsion smeared and speckled, and the image so warped that it’s as if seeing the figure through a fogged window or time-misted memory. On either side, soft, dense black pillars mark out the photographic frame, giving lie to any semblance of verisimilitude. Remember the artifice, they say. We’re blocked out twice: once by the woman’s posture, then again by the artist. Exactly when Maar altered the negative is unknown — and the reasons why — create a third, additional layer of occlusion. With remarkable consistency, Maar manages to elude easy visual, semantic and biographic categorisation.

The scope of the Tate Modern’s Dora Maar exhibition is admirable. It makes room for her work far beyond the photomontages for which she is best known and includes sections dedicated to her street photography in Spain and London. Over here is a Pearly Princess looking fabulous and self-possessed on the pavement in what might be Bloomsbury. Over there is a girl in a cloche hat star-fishing herself between the jambs of an exterior door. Even when the material isn’t overtly surreal, Maar captures the uncanny moments of the daily hurly burly. She’s a consummate looker, which means that between this documentary-reportage photographs and her commercial and artistic work emerge fascinatingly consistent ways of seeing the world. A mere five years after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, a photograph of a women selling lottery tickets in front of Midland Bank is tinged with irony as well as presenting her as a figure straight out of a fairy tale or opera.

The scope of the Tate Modern’s Dora Maar exhibition is admirable. It makes room for her work far beyond the photomontages for which she is best known and includes sections dedicated to her street photography in Spain and London. Over here is a Pearly Princess looking fabulous and self-possessed on the pavement in what might be Bloomsbury. Over there is a girl in a cloche hat star-fishing herself between the jambs of an exterior door. Even when the material isn’t overtly surreal, Maar captures the uncanny moments of the daily hurly burly. She’s a consummate looker, which means that between this documentary-reportage photographs and her commercial and artistic work emerge fascinatingly consistent ways of seeing the world. A mere five years after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, a photograph of a women selling lottery tickets in front of Midland Bank is tinged with irony as well as presenting her as a figure straight out of a fairy tale or opera.

Threaded throughout are portraits of the people she loved and with whom she worked. These show off her immense technical skills as well as recording her own life and those close to her. A gorgeous portrait of Nusch Eluard, her face delicately posed on slender fingers, is all softly-rounded surfaces and elegant curves; an adjacent print superimposes an inverted spider web over her features, the creature centrally crouched between her brows. A playful snap of Paul Eluard has him teasingly half-hidden behind a gigantic sunflower that droops its overblown head over his. Picasso is framed against his paintings and stares down her lens with intent confidence. Christian Bérard is caught horsing around by a fountain and Leonor Fini is captured seated between two statues, her seriously seductive pose offset by the humorous inclusion of a long-haired black cat settled between her legs. Yet Maar, though she features both behind and in front of the camera (see the portrait of her by Man Ray, for instance, who turned her down as a darkroom assistant before employing Lee Miller instead), remains somewhat of a cipher. The details of the studios she set up and worked in are clear enough, as is her place among the Surrealists, but her own inner life slips away, even as we learn more about her.

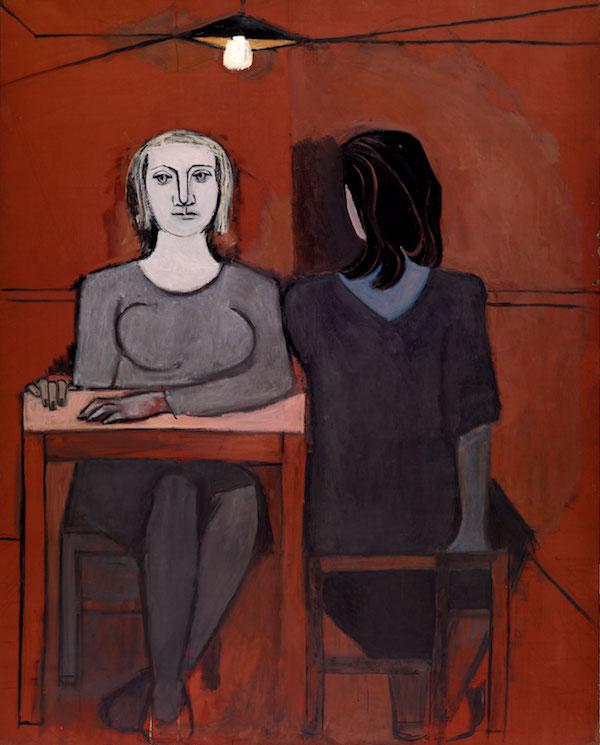

Consider the most directly autobiographical room, which is dominated by her magnificent painting, The Conversation, 1937 (pictured top). Though he is not pictorially present, Picasso features almost palpably. (It’s also worth noting that Maar’s stark bulb hanging from the ceiling later reappeared in his anti-war polemic, Guernica). In the painting, she depicts herself on the opposite side of a table to Picasso’s former lover (and mother of their daughter), Marie-Thérèse Walter, with whom Picasso remained close throughout the relationship with Maar. Maar’s back is to us so we cannot see her face, though her body language is explicit enough: while her feet point away from the table, her head is turned to face Walter, as if she is looking at her in spite of herself or because she feels it to be some kind of duty. Her right hand braces the chair behind her back to keep her from reverting to her original position and her left arm appears to ply across her body in comfort or protection. Her body is neatly tucked, so that in the painting she is defined by her dress and appears as a solid pillar of grey. Yet we learn just as much (if not more) about her from her depiction of Walter. She occupies a confident, full frontal position at the table, her legs elegantly crossed at the ankles and her arms on its top — but her entire being skews away from Maar. Her elbows are out and defensive, her eyes slips sideways, their focus out of frame. It’s clear she wishes to will herself not to see her. A good portraitist must be both outgoing and self-effacing as bringing other people out is the focus. So even when Maar depicts herself, the clearest picture comes through the intermediary of other people.

An exhibition should not necessarily be governed by biography, but the curation performs a very delicate balancing act between Maar and the people in her life. In the penultimate room hangs a self-portrait which glancingly mentions a period of post-breakdown trauma (from 1945 to the 1950s, when several people close to her died in the wake of the end of the relationship with Picasso) during which she was treated by French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. The glancing nature of the reference seems a kind of reluctance to mention yet another influential man in her life, for it might threaten to tip the course of the exhibition in their favour. It feels as if the reference is made in order to sink. The conclusion of the show are her late, camera-less photographs in which she acts directly on her materials, painting with light and chemicals, without the intervention of a lens (some pictured above). By the time of her death in 1997 she was 90 and practically a recluse. But, just possibly, it was the first time she had really allowed herself to be seen.

An exhibition should not necessarily be governed by biography, but the curation performs a very delicate balancing act between Maar and the people in her life. In the penultimate room hangs a self-portrait which glancingly mentions a period of post-breakdown trauma (from 1945 to the 1950s, when several people close to her died in the wake of the end of the relationship with Picasso) during which she was treated by French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. The glancing nature of the reference seems a kind of reluctance to mention yet another influential man in her life, for it might threaten to tip the course of the exhibition in their favour. It feels as if the reference is made in order to sink. The conclusion of the show are her late, camera-less photographs in which she acts directly on her materials, painting with light and chemicals, without the intervention of a lens (some pictured above). By the time of her death in 1997 she was 90 and practically a recluse. But, just possibly, it was the first time she had really allowed herself to be seen.

- Dora Maar is at Tate Modern until 15th March 2020

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment