Eileen Agar, Whitechapel Gallery review - a free spirit to the end | reviews, news & interviews

Eileen Agar, Whitechapel Gallery review - a free spirit to the end

Eileen Agar, Whitechapel Gallery review - a free spirit to the end

An important female surrealist gets her first retrospective

Eileen Agar was the only woman included in the International Surrealist Exhibition of 1936, which introduced London to artists like Salvador Dali and Max Ernst. The Surrealists were exploring the creative potential of chance, chaos and the irrational which they saw as the feminine principle, yet they didn’t welcome women artists into their group.

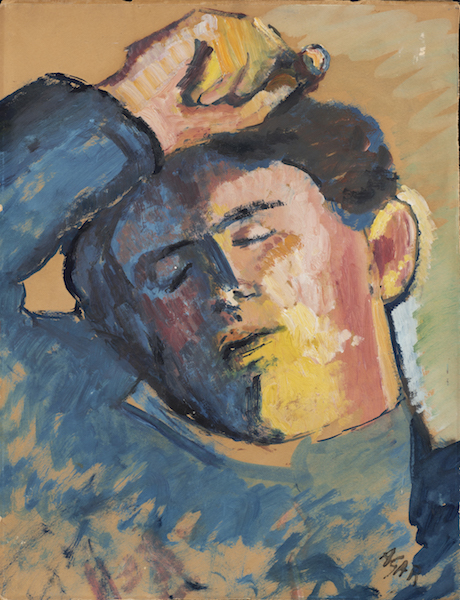

Agar wasn’t easily discouraged, though. At the tender age of six, she’d been sent away to boarding school, an experience that made her fiercely independent. Later she studied at the Slade, but rebelled against the art school’s academic approach. A portrait from 1929 (pictured right) shows her to be a powerful painter. Strong Fauvist colours create a tender likeness of her partner, the Hungarian writer Joseph Bard. Warm reds, pinks and yellows light one side of the sleeping man’s face, while cool blues and blacks create the shadow side.

Agar wasn’t easily discouraged, though. At the tender age of six, she’d been sent away to boarding school, an experience that made her fiercely independent. Later she studied at the Slade, but rebelled against the art school’s academic approach. A portrait from 1929 (pictured right) shows her to be a powerful painter. Strong Fauvist colours create a tender likeness of her partner, the Hungarian writer Joseph Bard. Warm reds, pinks and yellows light one side of the sleeping man’s face, while cool blues and blacks create the shadow side.

That same year the couple took off for Paris where they met André Breton and Paul Elouard. Agar was drawn to the Surrealists’ use of found images and objects, but she was also studying with the cubist painter Fratisek Foltyn. And during a career spanning nearly 70 years, her aim was to combine these disparate languages into a fusion she described as “the interpenetration of reason and unreason.“

Today she is best known for sculptures like the Angel of Anarchy 1936 (pictured left), a plaster cast of Bard’s head draped in beads and feathers, studied with diamante and swathed in silk scarves. If this flamboyant character seems slightly malign, it’s companion the mask-like Angel of Mercy, which is painted in geometric patterns, is similarly ambiguous. The pair are like talismans, personifying her Surrealist and Cubist tendencies.

Today she is best known for sculptures like the Angel of Anarchy 1936 (pictured left), a plaster cast of Bard’s head draped in beads and feathers, studied with diamante and swathed in silk scarves. If this flamboyant character seems slightly malign, it’s companion the mask-like Angel of Mercy, which is painted in geometric patterns, is similarly ambiguous. The pair are like talismans, personifying her Surrealist and Cubist tendencies.

Agar also made another assemblage from blue-painted cork decorated with shells, corals, seaweed and assorted marine bric a brac, which she humorously described as “Archimboldo head gear for the fashion conscious”. The V&A owns this wonderful sculpture which, sadly, isn’t included in the Whitechapel show. Instead, there’s newsreel footage of the artist wearing an earlier version of the hat (main picture). The inane voice-over is a timely reminder of how women have been routinely patronised, and how this has led to female artists being marginalised or overlooked altogether.

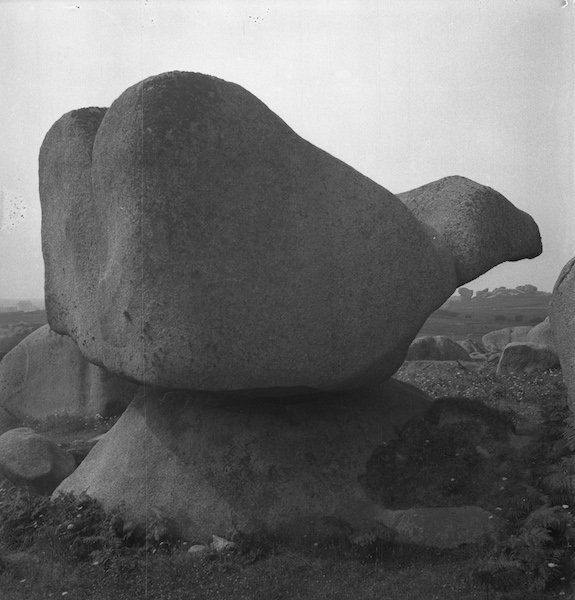

1936 was a good year for Agar. In Ploumanach, France she photographed a group of rocks eroded by the sea into extraordinary shapes often resembling naked bodies, which she described as like “a show of sculpture in the open air” (pictured below right: Bum and Thumb Rock © Tate images). Friends like Picasso, Dora Maar, Roland Penrose and Lee Miller were also caught on camera along with odd things that caught her eye, some of which found their way into her collages.

Agar was extremely prolific and seeing so much of her work brought together is a delight. The collages are especially fine. Her huge store of pictures included anatomical studies and X rays of the human body plus all kinds of sea creatures. She continually refers to the ocean, seeing it as a metaphor for the unconscious. Erotic Landscape 1942 (pictured below) is a multi-layered cornucopia. Superimposed onto abstract shapes, her naked body is overlain with fish, seaweed and cellular structures suggestive of abundance; but there’s also an undertow of darkness.

Agar was extremely prolific and seeing so much of her work brought together is a delight. The collages are especially fine. Her huge store of pictures included anatomical studies and X rays of the human body plus all kinds of sea creatures. She continually refers to the ocean, seeing it as a metaphor for the unconscious. Erotic Landscape 1942 (pictured below) is a multi-layered cornucopia. Superimposed onto abstract shapes, her naked body is overlain with fish, seaweed and cellular structures suggestive of abundance; but there’s also an undertow of darkness.

As part of the war effort, the couple worked in a soup kitchen, served as fire watchers and opened their London home to refugees. It was a bleak time and, for many years afterwards, Agar was dogged by “a sense of despondency”. She had begun experimenting with poured paint and in Portrait 1949, a figure emerges from pools of dark green and black pigment like a lost soul gradually surfacing from despair. It seems very much like a self-portrait.

“Surely room must be made for joy in this world?” she wrote later; she continued working, but it would be a while before her palette lightened. In Collective Unconscious 1977 geometric shapes are juxtaposed with floral motifs, a head and large shell to suggest the interconnection of human, organic and abstract forms and to embody the synthesis between reason and unreason she had been striving for.

Then in the mid-1980s, when she was in her eighties, she translated her rock photographs into paintings whose heightened colours are like a defiant burst of exuberance. She died in 1991 having remained a free spirit until the end.

Then in the mid-1980s, when she was in her eighties, she translated her rock photographs into paintings whose heightened colours are like a defiant burst of exuberance. She died in 1991 having remained a free spirit until the end.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment