Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet, Royal Academy review – strange and intriguing | reviews, news & interviews

Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet, Royal Academy review – strange and intriguing

Félix Vallotton: Painter of Disquiet, Royal Academy review – strange and intriguing

An avant-garde artist who paints like Holbein

Félix Vallotton is best known for his satirical woodcuts, printed in the radical newspapers and journals of turn-of-the-century Paris. He earned a steady income, for instance, as chief illustrator for La Revue blanche, which carried articles and reviews by leading lights such as Marcel Proust, Alfred Jarry and Erik Satie. You can see the influence of Japanese prints in the flattened spaces, simplified shapes and unusual viewpoints that give a comic slant to scenes of Parisian life.

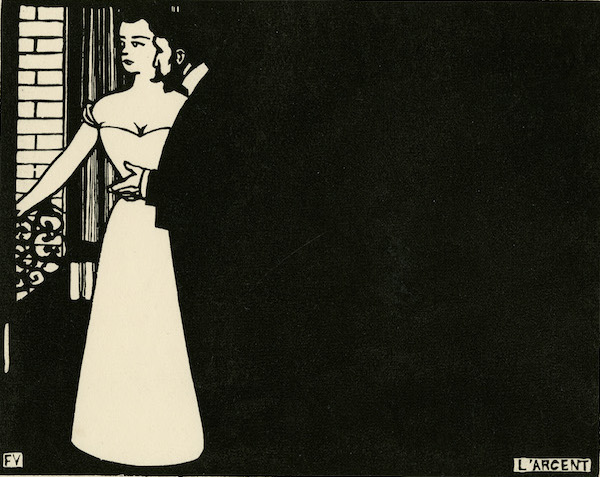

In contrast to the comedy of the streets, life indoors is fraught with tension. In Intimacies the lies, deceits and obfuscations of married life are translated into terse little vignettes, which tell their story through close observation of posture and gesture. In Money 1898 (pictured below right) a woman turns away from her husband or lover. They are poles apart. Dressed in white, she stands in the light of an open window; wearing black, he merges with the interior darkness. Her icy demeanour and his gesturing apology speak eloquently of disappointment, hurt and guilt. It could be a scene from a novel by Émile Zola.

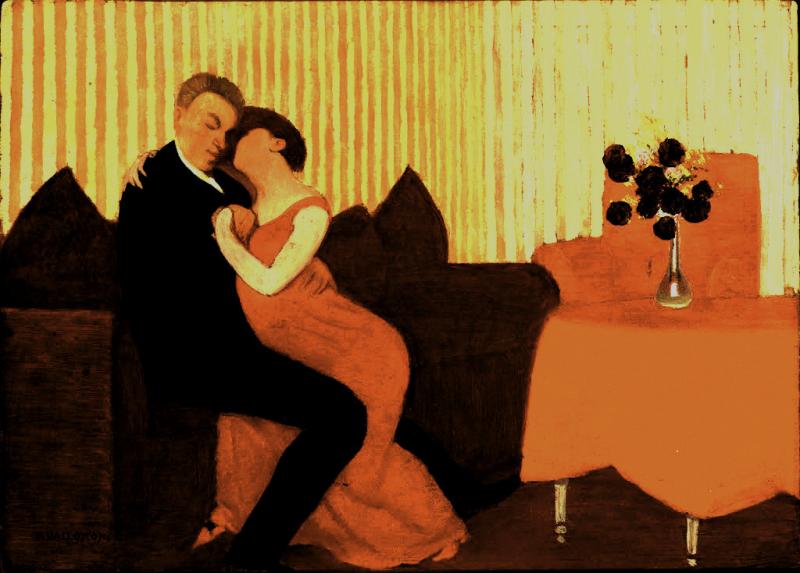

Vallotton was also an ambitious painter and he realised some of the scenes in oils. The results can be sublime. In The Lie, 1897 (main picture) the black and white print is translated into black, crimson, red and soft pink which lends a blissful glow to the embracing couple. But the insistent stripes of the wallpaper and the jarring red of the armchair and tablecloth sound the alarm; based on a lie, this harmony is unlikely to last.

In its amazing simplicity, The Theatre Box 1909 is incredibly radical. From where we sit, only the heads of the couple in the box are visible. The yellow balustrade, that hides them, takes up nearly half the picture; the rest is darkness punctured by their dimly lit faces and her big hat. The stroke of genius is her gloved hand, a tiny 3 dimensional fist resting on the balustrade and casting a diagonal shadow. To find another painting as daringly sparse as this, you need to fast forward 20 years to the American painter, Georgia O’Keeffe or 50 years to Wayne Thiebaud.

In 1899 Vallotton joined the ranks of the bourgeoisie, whom he’d satirised so mercilessly, by marrying a rich widow, Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques, daughter of the influential art dealer, Alexandre Bernheim. His charming 1905 portrait of her (pictured below left) shows a vivacious woman enjoying her own thoughts as she relaxes on a sofa. At the family dinner table he appears only as a black silhouette, though, and the apparently endless vista of rooms opening off one another in Interior with Woman 1909 suggest that he felt ill at ease in her luxurious apartment.

Alongside the gems, Vallotton also produced some ham-fisted mistakes blighted by crass colours, turgid paint handling, wooden figures and clunky simplification. How astonishing, then, that he also excelled in the crystaline realism perfected by Dutch still life painters in the seventeenth century. The exhibition opens with a still life from 1887 of a cup and saucer beside a silver coffee pot whose surface is enlivened by exquisite reflections. Vallotton was to set these skills aside when he joined his friends, Bonnard and Vuillard in their avant garde group, the Nabis and began translating into paint the simplifications demanded by the woodcut technique.

Alongside the gems, Vallotton also produced some ham-fisted mistakes blighted by crass colours, turgid paint handling, wooden figures and clunky simplification. How astonishing, then, that he also excelled in the crystaline realism perfected by Dutch still life painters in the seventeenth century. The exhibition opens with a still life from 1887 of a cup and saucer beside a silver coffee pot whose surface is enlivened by exquisite reflections. Vallotton was to set these skills aside when he joined his friends, Bonnard and Vuillard in their avant garde group, the Nabis and began translating into paint the simplifications demanded by the woodcut technique.

In Red Peppers, 1915, though, he returns to the hyper subtle realism of that early still life, contrasting the glistening skin of the vegetables with the chilly white opacity of the marble table top. So far so traditional; but two years earlier Vallotton created one of the strangest and most contradictory paintings ever produced. The White and the Black (pictured below) is a riff on Manet’s Olympia 1863, which features a black servant delivering a bouquet of flowers to a white prostitute. Vallotton’s nude lies asleep, her cheeks flushed perhaps with sexual exertion. Her pearly pink flesh and auburn hair are painted with the delicacy of the Ingres nudes he admired; so is this a homage to the tradition?

The black woman sitting on the bed with a fag in her mouth is painted with the same precision. With her blue satin dress and orange topknot, she looks too smart to be a servant, so is she the procuress, the lover or a friend? The background gives no clue, for it, too, is oddly inconsistent. The women are offset by a turquoise wall as flat as a hard-edge abstraction. If asked to date this anomalous picture, I’d have said it was an exploration of race and gender painted in the 1960s, probably by a woman. With reference to the domestic tensions he portrays, the Royal Academy has dubbed Vallotton the “painter of disquiet”; they make no mention, though, of the art historical disquiet he generates with his stylistic regressions into the past, at one end of the spectrum, and precocious leaps into the future, at the other.

With reference to the domestic tensions he portrays, the Royal Academy has dubbed Vallotton the “painter of disquiet”; they make no mention, though, of the art historical disquiet he generates with his stylistic regressions into the past, at one end of the spectrum, and precocious leaps into the future, at the other.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment