Fabienne Verdier, The Song of the Stars (Le chant des étoiles), Musée Unterlinden, Colmar review - sacred and contemporary art in dialogue | reviews, news & interviews

Fabienne Verdier, The Song of the Stars (Le chant des étoiles), Musée Unterlinden, Colmar review - sacred and contemporary art in dialogue

Fabienne Verdier, The Song of the Stars (Le chant des étoiles), Musée Unterlinden, Colmar review - sacred and contemporary art in dialogue

The French artist is inspired by the Matthias Grünewald altarpiece

I have wanted to visit the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar for many years: the home of Matthias Grünewald’s masterpiece, the Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-1516), one of the great works of North European religious art. The opportunity finally arose in an oblique way, as the museum has been hosting a major exhibition by the French painter Fabienne Verdier.

The show was commissioned as an invitation for the artist to respond to the Grünewald and other works in a treasure trove that lies hidden away in the east of France, only just over two hours train from Paris, and yet somewhat off the beaten track.

Fabienne Verdier is a dedicated explorer, in love with the challenge of adventure. Her career as an artist began with a 10-year stay in China, soon after she left art school, not long after the destructive chaos of the Cultural Revolution, when she sought training – technical as well as philosophical – from Taoist masters. On her return to Europe, she made work that embodied much of what she had learned in the East, but drew inspiration as well from the great American Abstract Expressionists, for whom gesture and presence played an essential role that mirrored the practice of Taoist thought.

Verdier developed a wholly original way of painting, with very large brushes suspended above the floor and running on overhead rails, allowing the force of gravity to carry the paint downwards. In tune with the wisdom and practice of the Chinese masters, she sought to embody in her brush and her gestures the forces and energy of nature. Nature was immanent in the work rather than portrayed literally. She sought to communicate the essence in the movement of water, the telluric forces of mountains or the shifting shapes of windswept clouds.

Verdier developed a wholly original way of painting, with very large brushes suspended above the floor and running on overhead rails, allowing the force of gravity to carry the paint downwards. In tune with the wisdom and practice of the Chinese masters, she sought to embody in her brush and her gestures the forces and energy of nature. Nature was immanent in the work rather than portrayed literally. She sought to communicate the essence in the movement of water, the telluric forces of mountains or the shifting shapes of windswept clouds.

Alongside her explorations of painting that would embody the currents of nature's energy in many of its manifestations, Fabienne Verdier has enjoyed a number of creative dialogues, starting with an invitation from the Swiss collector Hubert Looser, who commissioned her to makes works that could hang alongside paintings and sculptures by Willem de Kooning, Cy Twombly, Richard Serra and others. She continued with a major exhibition at the Groningen Museum in Bruges, where she made work inspired by the Flemish Masters in their collection, major paintings by Gerard David, Van Eyck and others. Not long after, she was invited to work as a resident artist by the Juilliard School of Music in New York, where she spent three months making work alongside musicians and singers, with music that ranged from Elliott Carter to improvised jazz. Here again, she was seeking to bring to life a correspondence between the act of making art and the process of composing and performing music.

This has not been the journey of a dilettante, but a quest on Verdier’s part for the essence of what moves the world as well as the artist, as if the work of creative art might just be another – in this case microcosmic – manifestation of the continuous cycles that produce constant change in the universe. Part of the show in Colmar presents some of the French artist’s most striking works in dialogue with a number of paintings in the Unterlinden museum’s permanent collection: the dialogue creates juxtapositions, which the visitor can take on board or not, according to form, texture and colour. Cranach’s “Melancholia” (1532) and Verdier’s “Clairvoyance” are not obvious partners, one abstract and the other richly allegorical, but there is something of the mood and drama evoked in both that resonates. Similarly a crazy and colourful Dubuffet sculpture “Don Coucoubazar”(1973) sits perfectly well alongside Verdier’s “Vide Vibration”. There is echo of the interplay between life and death in the combination of Verdier's "La Dormition" and Jean-Jacques Henner's "Jeune baigneur endormi" (1895, pictured below). The often surprising experience of discovering Verdier’s paintings among other artists’ work provides a context and introduction to the climax of the show, which leads the visitor into a vast, and high-ceilinged space, the Ackerhof (main picture), a new building designed by Herzog and de Meuron, which mirrors the large vaulted chapel across the courtyard, in which the Grünewald altarpiece is exhibited. The effect on entering this space is very striking: there are 78 circular paintings hung on either side of the high walls, with a riotous display of colour that contrasts very starkly with the gestural force of the more sober expressionist or calligraphic work which has characterised the artist’s work so far. At the very end of the avenue of “Rainbow Paintings”, there is a “Vortex” in a more familiar style, which evokes the energy of the breath that so many cultures imagine being at the heart of creation.

The often surprising experience of discovering Verdier’s paintings among other artists’ work provides a context and introduction to the climax of the show, which leads the visitor into a vast, and high-ceilinged space, the Ackerhof (main picture), a new building designed by Herzog and de Meuron, which mirrors the large vaulted chapel across the courtyard, in which the Grünewald altarpiece is exhibited. The effect on entering this space is very striking: there are 78 circular paintings hung on either side of the high walls, with a riotous display of colour that contrasts very starkly with the gestural force of the more sober expressionist or calligraphic work which has characterised the artist’s work so far. At the very end of the avenue of “Rainbow Paintings”, there is a “Vortex” in a more familiar style, which evokes the energy of the breath that so many cultures imagine being at the heart of creation.

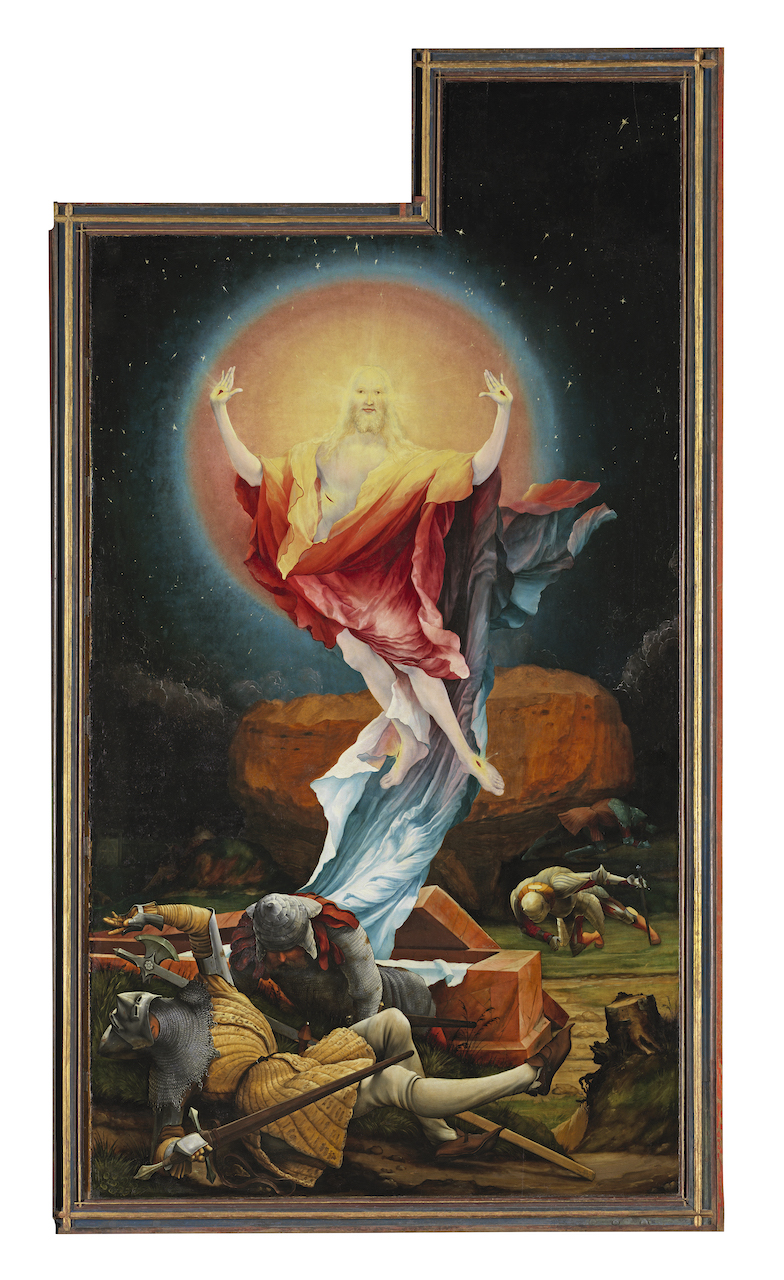

The installation was directly inspired by Grünewald’s “Isenheim Altarpiece”, more specifically by the resurrected Christ, levitating above his tomb, his arms reaching out in grace-filled offering, and surrounded by a rainbow-like aura unique in Western painting (pictured below). After weeks of reflection as to how she would draw inspiration from the various panels of the Altarpiece, Verdier had an epiphany. While she was watering a garden, standing in a pool of blazing sunlight, the droplets of water, catching the light, created a rainbow, a few metres before her. She knew, at this revelatory moment, that she must work with the wonders that are light and colour, and the illusory nature of refracted light’s transformation into many colours. The image of Christ’s resurrection, the subtle yet magical dialogue between presence and absence, and the essence of life as constant interaction between life and decay and rebirth – all of these ideas fed into her research and the explorations that produced the remarkable paintings assembled in this installation.

Although her work has always been immensely grounded, not least because her body is so present in every gesture, for Verdier, painting is a means for exploring philosophy. In this respect, she is quintessentially French: she reads widely, creates beautiful notebooks that chronicle her journey, and takes great pleasure in conversing, for instance, with the astrophysicist Trinh Xuan Thuan, a scientist with a decidedly philosophical bent, who writes with wonder about the infinite mystery of the universe. These conversations fed into the “Rainbow Paintings”, which allude in many ways – both visually and conceptually to the birth and death of stars – once again the theme of resurrection central to Grünewald’s resplendently reborn Christ.

The ambition of the project – which Verdier has also imagined as a kind of requiem for victims of the COVID pandemic – is considerable, just as with Grünewald’s Altarpiece, which was commissioned in the face of the many deaths caused by the scourge of deadly ergotism or St Anthony’s Fire in early 16th century Germany. The Isenheim Altarpiece was intended to offer healing, presenting Christ crucified as a pock-marked victim of the plague. As might befit a grand gesture by the church, there is something grandiloquent and over-reaching in the panels: it may be that the recent restoration of the works has produced over-saturated colours, but there is something bordering on the kitsch, a display of both technique and evocation of horror that were no doubt effective at a time without film or television.

The ambition of the project – which Verdier has also imagined as a kind of requiem for victims of the COVID pandemic – is considerable, just as with Grünewald’s Altarpiece, which was commissioned in the face of the many deaths caused by the scourge of deadly ergotism or St Anthony’s Fire in early 16th century Germany. The Isenheim Altarpiece was intended to offer healing, presenting Christ crucified as a pock-marked victim of the plague. As might befit a grand gesture by the church, there is something grandiloquent and over-reaching in the panels: it may be that the recent restoration of the works has produced over-saturated colours, but there is something bordering on the kitsch, a display of both technique and evocation of horror that were no doubt effective at a time without film or television.

Grünewald’s near-overkill may have set the scene for the massive scale of Verdier’s installation (pictured below). The overall impression when entering the Herzog and de Meuron "chapel" is overwhelming, not unlike the impact of the wall-to-wall Giotto murals in the early 16th century Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. The individual paintings undeniably pack a remarkable punch: Verdier has developed a screen-printing technique that enables her to merge one colour with another, much in the manner of a rainbow – suggesting the blurring between singular hues, and the immateriality of light. In the centre of each circle, there are her signature splashes of paint, as well as brushstrokes. For my part, I found looking at each individual painting more engaging than trying to take in half a dozen of them, or the entire surrounding spread of the installation. Might, I wondered, the Grünewald’s polyphony of colour have inspired Verdier to go for excess, rather than the contained and yet super-charged energy of her previous work? There is grandeur here – the ambitious scale is breath-taking – but at a cost: the colours sometimes clash, producing a kind of diffusion. There is impressive technical prowess, and a kaleidoscope of inspiring ideas. I felt the individual works might require a little more space to make the most of their undeniable individual agency. Having said that, the exhibition is well worth seeing – a comprehensive survey of Fabienne Verdier’s work, as well as her new explorations. There is also the unmissable Musée Unterlinden, which doesn’t just boast the restored Grünewald but a wonderful collection of paintings by local artist Martin Schongauer (1450/1453-1491) and other late medieval and early Renaissance works, but a more than respectable display of 20th century art. Herzog and de Meuron, experts at adapting period buildings to modern use, have done a great job here: the spiral staircases they have designed alone are sufficient reason for a visit from anyone interested in contemporary architecture that has a timeless feel to it as well as being innovative.

Having said that, the exhibition is well worth seeing – a comprehensive survey of Fabienne Verdier’s work, as well as her new explorations. There is also the unmissable Musée Unterlinden, which doesn’t just boast the restored Grünewald but a wonderful collection of paintings by local artist Martin Schongauer (1450/1453-1491) and other late medieval and early Renaissance works, but a more than respectable display of 20th century art. Herzog and de Meuron, experts at adapting period buildings to modern use, have done a great job here: the spiral staircases they have designed alone are sufficient reason for a visit from anyone interested in contemporary architecture that has a timeless feel to it as well as being innovative.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment