Artist George Stubbs liked horses. The MK Gallery’s exhibition “all done from Nature” will try to convince you that he also cared about people. He did, to an extent; the commissions came that way. But about half way through the exhibition, the diminutive Study for Three Hunters and Two Grooms Waiting in a Stable-Yard, 1765-70, gives pause for thought. The detailed study depicts a horse with pensive eyes and toned flanks. One back hoof is elegantly raised, as if ready for parade. Its ears are perkily alert. It is a clever creature. Yet where bridle and saddle should be is empty space. Its back is wholly missing and the horse is divided in two by a belt of blank paper down its belly. A paper stripe runs along the jowl. Yoked by a human, Stubbs seems to suggest, the horse is a lesser beast.

As writer Nicholas Clee tartly notes, “The greatest painter of racehorses did not like horseracing.” For Stubbs, the determined, idiosyncratic son of a Liverpool leather-worker, people were fine but animals were better. “All done from Nature” is divided roughly into human and animal subjects. The first half concentrates on the people who played key roles in his life and feels much like a pictorial biography. These include the Wedgwoods (Josiah and Sarah Wedgwood with their Seven Children in the Grounds of Etruria Hall, 1780) whose family portrait allowed Stubbs to pay Josiah back for having developed large earthenware plaques for the purpose of painting large-scale enamels. Also on display is his earliest painting, Sir Henry Nelthorpe and his Second Wife, Elizabeth, c 1746. The couple look a little staid and peculiar, but it’s far from an unsympathetic portrait. It is thought it was Elizabeth who arranged for Stubbs to spend 18 months dissecting 12 horse carcasses in a barn in Lincolnshire, the result of which was his magisterial study, The Anatomy of the Horse, 1756-58 (pictured below, seen through the skeleton of Eclipse). Not so Lord Pigot (Lord Pigot of Patshull riding a Spanish-bred Charger, 1765-68) whose reputation for coercion and cruelty as Governor of Madras and President of the East India Company might be read in his forceful handling of his white steed. It foams at the mouth and its neck is uncomfortably arched.

These portraits, which track the networks of patronage that Stubbs relied upon for his work, culminate in the third room, filled with portraits of horses, often accompanied by their owners, jockeys or grooms. They are self-conscious tokens of aristocratic prestige and high breeding, both human and creaturely. Many of the paintings have remained in the families of their original commissioners, adding significance to the way these people – mostly men – stare out of the canvas. Perhaps Joseph Smyth, Lieutenant of Whittlebury Forest stood in front of his equestrian portrait, catching his own painted glance and musing on his administrative duties. Perhaps Sir John Nelthorpe’s descendants stood in the same spot he himself had, decades or even centuries later. It’s the horses though – and to a lesser extent, the dogs – which are the principal focus. Each has a distinct character and bears the marks of its treatment. Molly Long-Legs, an ambitious racing steed, is impatient with the bit and bright-eyed. Her prominent ribs are evidence of having been “sweated”, likewise her long skinny pins (Molly Long-Legs with a Jockey, 1762). Blank, a horse of high breeding with a better record as a stallion than a racer, is shown as cheeky and spirited, rearing vigorously against his groom’s handling (The Duke of Ancaster’s Bay Stallion, Blank, held by Old Parnam, His Groom, 1761). These beasts are unconcerned by their place in history and nobler for it.

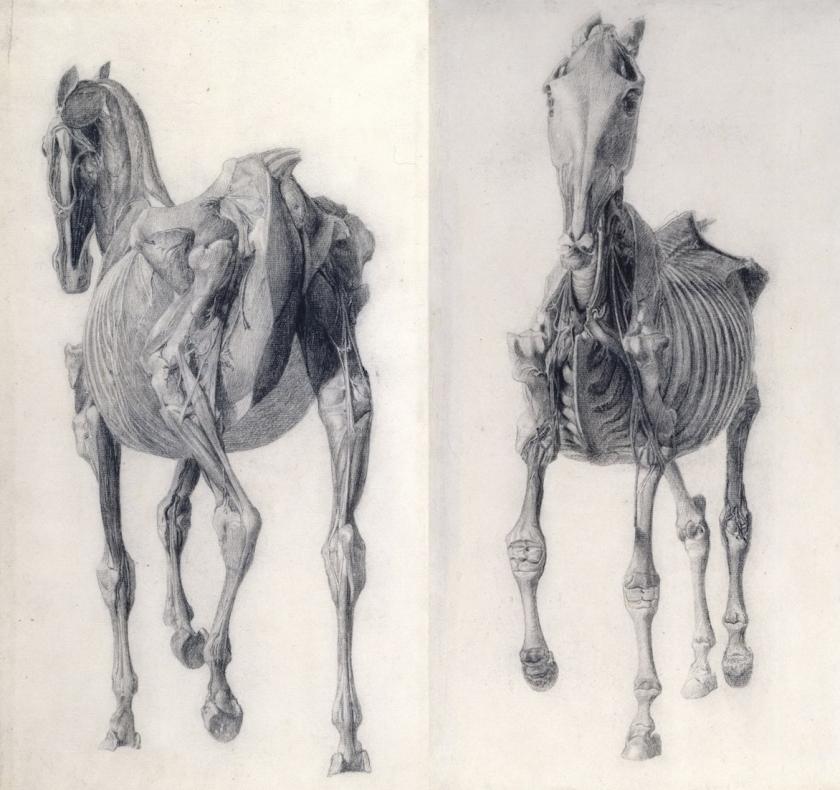

These portraits, which track the networks of patronage that Stubbs relied upon for his work, culminate in the third room, filled with portraits of horses, often accompanied by their owners, jockeys or grooms. They are self-conscious tokens of aristocratic prestige and high breeding, both human and creaturely. Many of the paintings have remained in the families of their original commissioners, adding significance to the way these people – mostly men – stare out of the canvas. Perhaps Joseph Smyth, Lieutenant of Whittlebury Forest stood in front of his equestrian portrait, catching his own painted glance and musing on his administrative duties. Perhaps Sir John Nelthorpe’s descendants stood in the same spot he himself had, decades or even centuries later. It’s the horses though – and to a lesser extent, the dogs – which are the principal focus. Each has a distinct character and bears the marks of its treatment. Molly Long-Legs, an ambitious racing steed, is impatient with the bit and bright-eyed. Her prominent ribs are evidence of having been “sweated”, likewise her long skinny pins (Molly Long-Legs with a Jockey, 1762). Blank, a horse of high breeding with a better record as a stallion than a racer, is shown as cheeky and spirited, rearing vigorously against his groom’s handling (The Duke of Ancaster’s Bay Stallion, Blank, held by Old Parnam, His Groom, 1761). These beasts are unconcerned by their place in history and nobler for it. For this reason, the room, which contains Whistlejacket, c 1762, is where the exhibition really comes together. Here Stubbs shows himself sensitive to his subjects’ inner lives. Hanging adjacent – and also set against a plain background – are a pair of stunning group portraits commissioned by the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham: one of stallions, another of mares and foals (pictured above). The dynamics between the individuals are as social as they are aesthetic, the rise and fall of easy communion resulting in a flowing, frieze-like composition. In The Anatomy of the Horse, also on display, Stubbs’s scientific and artistic eye combine in a work clearly the result of both determination and focus. During the 18 months he spent dissecting horses, Stubbs invented and installed lever mechanisms that allowed him to winch entire carcasses into different positions by himself. The resulting engravings are striking for their detail and the way it is possible to look through the horse – from sternum to croup and vice versa. Under Stubbs’s questing, anatomical eye, the horse peels away. Over four engravings, muscles, hocks, tracheas and veins are revealed. In contrast to the Study, the more the horse is stripped, the more marvellous it becomes.

For this reason, the room, which contains Whistlejacket, c 1762, is where the exhibition really comes together. Here Stubbs shows himself sensitive to his subjects’ inner lives. Hanging adjacent – and also set against a plain background – are a pair of stunning group portraits commissioned by the 2nd Marquess of Rockingham: one of stallions, another of mares and foals (pictured above). The dynamics between the individuals are as social as they are aesthetic, the rise and fall of easy communion resulting in a flowing, frieze-like composition. In The Anatomy of the Horse, also on display, Stubbs’s scientific and artistic eye combine in a work clearly the result of both determination and focus. During the 18 months he spent dissecting horses, Stubbs invented and installed lever mechanisms that allowed him to winch entire carcasses into different positions by himself. The resulting engravings are striking for their detail and the way it is possible to look through the horse – from sternum to croup and vice versa. Under Stubbs’s questing, anatomical eye, the horse peels away. Over four engravings, muscles, hocks, tracheas and veins are revealed. In contrast to the Study, the more the horse is stripped, the more marvellous it becomes. The distinguishing feature of Stubbs’s work is not so much artistry as curiosity. Where something, someone or some creature has taken his fancy, the eye and the mind are rewarded. You see it in the very first pieces in the exhibition, the fascinating etchings he provided anonymously for John Burton’s An Essay Towards a Complete New System of Midwifery, Theoretical and Practical, 1751. Likewise in details such as the way the keeper of a cheetah holds its belt slipped between his ring and little finger (A Cheetah and a Stag with Two Indian Attendants, 1765), and in the almost comically personal portraits of the three soldiers standing to attention in Soldiers of the 10th Light Dragoons, 1793. In the final room, which concentrates on his depictions of the exotic creatures which were then entering private menageries, his studies of a mouse lemur go beyond merely conveying the habitual behaviour of the tiny mammal to imply a character and a disposition. It seems to tuck its tail round its haunches for comfort and plot nefarious schemes, its paws clutched before its chest. Did he overstep into anthropomorphism? Or is that the fault of the over-zealous viewer? When the rhino in his painting Rhinoceros, 1790-91 (pictured above) died of injuries inflicted as a result of its predeliction for sweet wine, it’s hard to be sure.

The distinguishing feature of Stubbs’s work is not so much artistry as curiosity. Where something, someone or some creature has taken his fancy, the eye and the mind are rewarded. You see it in the very first pieces in the exhibition, the fascinating etchings he provided anonymously for John Burton’s An Essay Towards a Complete New System of Midwifery, Theoretical and Practical, 1751. Likewise in details such as the way the keeper of a cheetah holds its belt slipped between his ring and little finger (A Cheetah and a Stag with Two Indian Attendants, 1765), and in the almost comically personal portraits of the three soldiers standing to attention in Soldiers of the 10th Light Dragoons, 1793. In the final room, which concentrates on his depictions of the exotic creatures which were then entering private menageries, his studies of a mouse lemur go beyond merely conveying the habitual behaviour of the tiny mammal to imply a character and a disposition. It seems to tuck its tail round its haunches for comfort and plot nefarious schemes, its paws clutched before its chest. Did he overstep into anthropomorphism? Or is that the fault of the over-zealous viewer? When the rhino in his painting Rhinoceros, 1790-91 (pictured above) died of injuries inflicted as a result of its predeliction for sweet wine, it’s hard to be sure.

- George Stubbs: "all done from Nature" at the MK Gallery until 26 January 2020

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment