“I was a nigger for twenty-three years. I gave that shit up. No room for advancement.” This astute joke, by American comedian Richard Pryor, is stencilled in black capitals on the gold ground of a painting by Glenn Ligon.

I’ve long admired the work of this black American minimalist. In the late 1980s he invaded the territory of pure abstraction – a bastion of white, middle-class males – and introduced content, usually in the form of texts taken from black authors or activists. So what appear to be all-black paintings after Ad Reinhardt turn out to be canvases densely layered with capital letters written in oil stick.

Despite being buried in murky blackness, a sentence or phrase usually remains legible; the message is always political and frequently refers to race. I Am a Man, 1988, was borrowed from the signs carried by black sanitation workers during their 1968 strike in Memphis.

The realm of “fine art” had been contaminated by references not just to real life, but to the political realities that allow white males to assume their position and status is natural (rather than acquired), their world view universal (rather than relative) and their art above or beyond politics.

The realm of “fine art” had been contaminated by references not just to real life, but to the political realities that allow white males to assume their position and status is natural (rather than acquired), their world view universal (rather than relative) and their art above or beyond politics.

Born in the Bronx to working-class parents, Ligon was considered “bright for a black boy”. His parents managed to get him a scholarship to Walden, a progressive, mostly white private school on the Upper West Side; so at the age of seven you could say he crossed an invisible line – from being seen as a second-class citizen to a child with potential or “room for advancement”, as Pryor would say.

Since his presence was the exception rather than the rule, he must have become aware that, basically, he was an outsider. Written in black capitals on a white ground, the sentence I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background, 1992, (pictured left) is from an essay by black anthropologist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston, but could easily refer to Ligon’s self-awareness as a black student at private school and university and, more recently, as an artist.

What makes his text paintings so powerful is that, while obeying the rules of decorum – they are supremely elegant – they follow their own agenda and reflect on his experience. He subverts his chosen field without degrading it and thereby enriches the host language in such a way that he makes pure, contentless abstraction seem vapid, or even deceiptful.

His Camden show is divided into two parts. Come Out (pictured below right) was inspired by a piece by composer Steve Reich made as a fund raiser for the Harlem Six, a group of black teenagers accused, in 1964, of murdering a white shopkeeper. On arrest, the boys were badly beaten by police and, in his testimony, Daniel Hamm described opening up the bruises “to let some of the blood come out” so he could get hospital treatment.

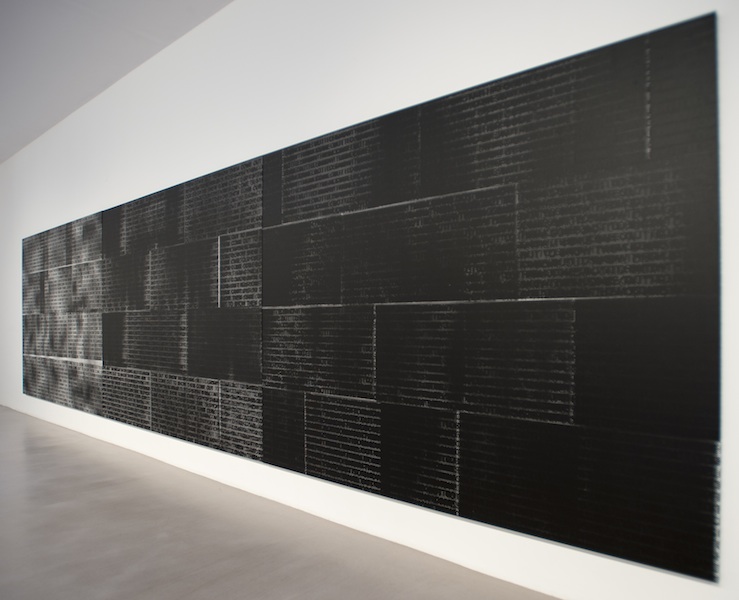

Reich looped the phrase on reel-to-reel tape so that, as they played, the tracks gradually went out of sink to create a multi-layered soundscape. Silkscreening the phrase “come out to show them” over and over onto large canvases, Ligon has created a visual equivalent of Reich’s composition; the pulses and rhythms of the overlaid words are comparable to the percussive beat of Hamm’s endlessly repeated voice.

Reich looped the phrase on reel-to-reel tape so that, as they played, the tracks gradually went out of sink to create a multi-layered soundscape. Silkscreening the phrase “come out to show them” over and over onto large canvases, Ligon has created a visual equivalent of Reich’s composition; the pulses and rhythms of the overlaid words are comparable to the percussive beat of Hamm’s endlessly repeated voice.

In his testimony, the teenager made a mistake using the word “blues” rather than “bruise”. In the blue light of police sirens and ambulances, two large neon signs read blues and bruise. Whereas neon has long been used as a medium for the exploration of personal politics – think Bruce Nauman and Tracey Emin – Ligon’s signs reveal the pressure placed on a black teenager trying to prove his innocence in the face of rigged evidence.

Both installations are beautiful, yet both refer to an event that happened a long time ago and are mediated via another artefact; Steve Reich seems as much the subject of the works as the Harlem Six. You could argue that, 50 years on, injustice for black youths is still rife in the United States, yet these pieces lack any sense of immediacy or relevance. They don’t upset any apple carts by revealing anything new and therefore sit happily within the canon of text-based art. It's as though Ligon has crossed another invisible line – to become part of the art world establishment making beautiful things for wealthy collectors.

Richard Pryor is the inspiration for Live, a seven-screen video installation (pictured left) in which clips of the comedian’s 1982 performance Live on the Sunset Strip are separated according to body parts; one screen shows footage of his head, another his hands, a third his shadow, and so on. Until now Ligon has focused exclusively on Pryor’s words, but the videos are silent, so forcing us to concentrate on the performer’s body language instead of his voice.

Richard Pryor is the inspiration for Live, a seven-screen video installation (pictured left) in which clips of the comedian’s 1982 performance Live on the Sunset Strip are separated according to body parts; one screen shows footage of his head, another his hands, a third his shadow, and so on. Until now Ligon has focused exclusively on Pryor’s words, but the videos are silent, so forcing us to concentrate on the performer’s body language instead of his voice.

Whereas Pryor’s jokes are provocative and inflammatory, his gestures are almost the opposite – subtle, non-confrontational and surprisingly feminine. By robbing him of his voice, Ligon has stripped him of the very thing that made him so important and, in the process, seems to have emasculated him. In these videos, Pryor becomes an elegant entertainer who poses little threat, and I fear that Glenn Ligon is in danger of moving in the same direction.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment