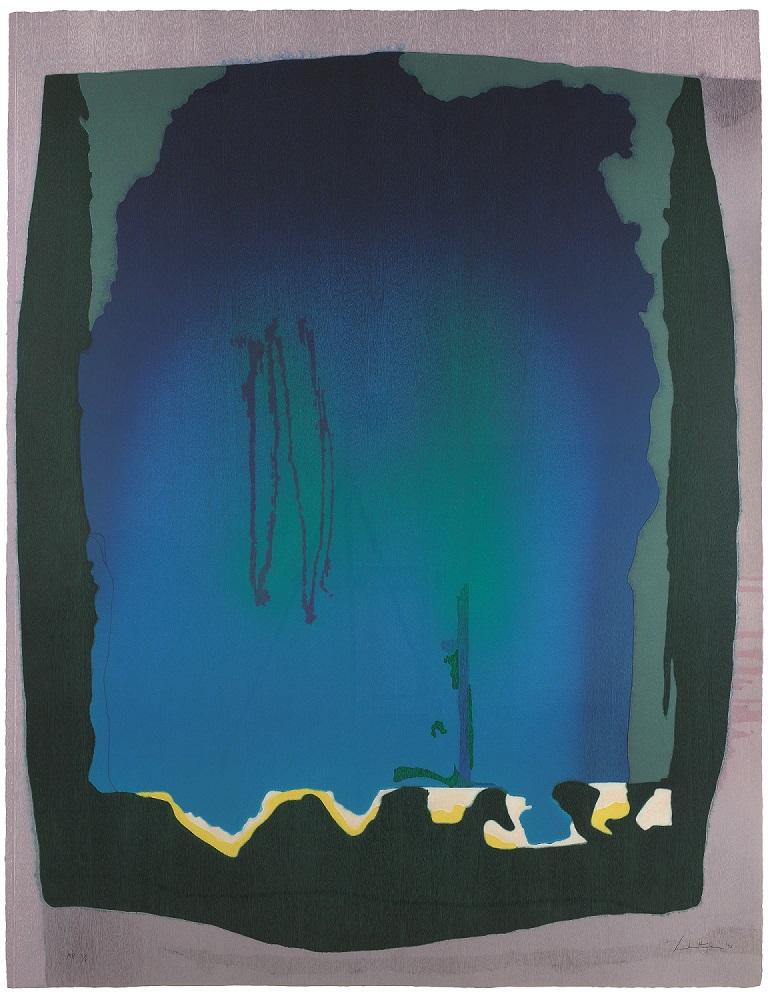

When you stand in front of Helen Frankenthaler’s Freefall, 1993, in your mind you drop into its gorgeous, blue abyss. It is enveloping, vertiginous, endless and yet there’s none of the terror of falling into a void, only intense, velvety comfort as the bluest blue melts into emerald green.

Its large scale, and gestural splashes of colour are supremely painterly, and yet this is not a painting but a print, its free flowing, spontaneous-looking marks the result of multiple, effortful iterations recorded in proof after painstaking proof (main picture: Freefall, 1993).

Helen Frankenthaler was one of the foremost post war American painters, whose innovative techniques introduced a characterful aesthetic, and blurred the boundaries between abstraction and figuration. Though she experimented with printmaking from the early 1960s, it was not until 1973 that she made her first woodcut print and this laborious, linear method seems at odds with the fluid, “born at once” aesthetic that is synonymous with her work.

For all that, her first work in this medium, East and Beyond, 1973, is unmistakably hers. Its forms, shaped using a jigsaw, are at once clearly delineated and spontaneous, and the very evident texture of wood, complete with imperfections, is as deceptively “real” as a photograph.

For all that, her first work in this medium, East and Beyond, 1973, is unmistakably hers. Its forms, shaped using a jigsaw, are at once clearly delineated and spontaneous, and the very evident texture of wood, complete with imperfections, is as deceptively “real” as a photograph.

Always an innovator, Frankenthaler created a technique of her own called “guzzying”, in which tools of all sorts – sandpaper, a cheese grater, even a dentist’s drill – are used to create texture on the surface of her woodblocks. These combined with papers specially developed with the help of her long term collaborator, the master printmaker Kenneth Tyler, result in prints that are a paradoxical distillation of all that is painterly. In Cameo, 1980, powdery blue and pink suggest light on water in a distinct echo of Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, 1872, achieved not with a paintbrush but with an eight-colour woodcut, and thick, absorbent pink handmade paper.

More often, Frankenthaler incorporates overt evidence of her materials, the natural characteristics of woodgrain introducing a peculiarly three-dimensional quality, while faults in the block are accepted as “happy accidents”, in a spirit that might naively be understood as a concern for “truth to materials”. In fact, “woodgrain” is often created not revealed, produced using various “guzzying” techniques, and with papers made specifically to create this effect. Sometimes, the effect sublimates into something new, and in Tales from Genji, 1998, woodgrain and paint, and perhaps subject matter, combine through some strange alchemy to suggest the shifting grain of shot silk.

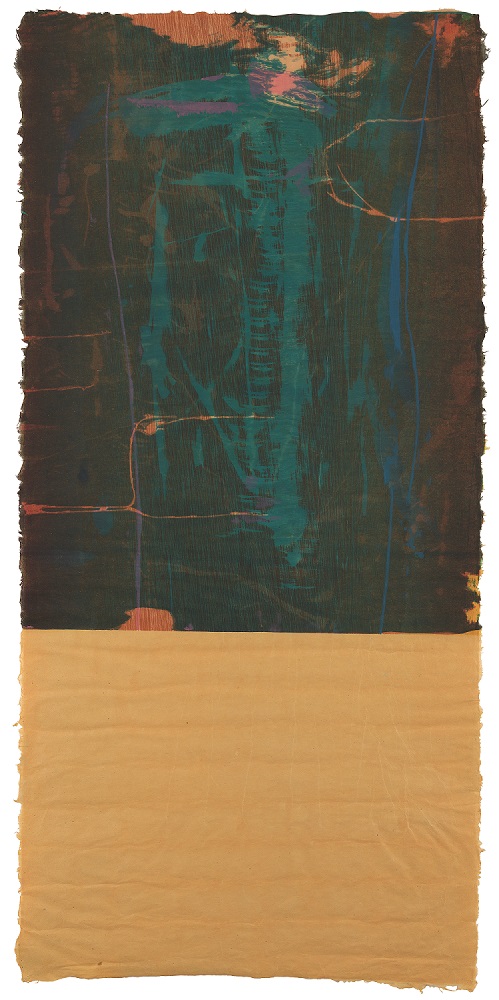

The integral importance of handmade papers is just one indicator of the complex, collaborative nature of the woodcuts, which marks them out from her solitary endeavours on canvas, which she continued in parallel to her printmaking. The exhibition makes only elliptical connections to her painting: proofs annotated with clear, decisive instructions attest to her clarity of vision, while Essence Mulberry, 1977 (pictured above right), assimilates the luscious colours of Renaissance prints with the juiciness of mulberries growing on a tree outside Kenneth Tyler’s workshop. Revealing and enjoyable as they are, such nuanced references to her artistic preoccupations assume a knowledge of her work that is unreasonable: Frankenthaler is just not sufficiently familiar that knowledge of her oeuvre can be taken for granted.

That said, the exhibition ends with a stylish footnote (albeit an expansive one), in a nearby gallery, easily missed but really worth seeing. Here Monet’s Waterlilies and Agapanthus, 1914-17, is hung with Frankenthaler’s painting Feather, 1973, rooting Frankenthaler’s abstraction within a European tradition, and underlining both artists’ shared interest in exploring nature’s own abstractions through the manipulation of materials.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment