High Spirits: The Comic Art of Thomas Rowlandson, The Queen’s Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

High Spirits: The Comic Art of Thomas Rowlandson, The Queen’s Gallery

High Spirits: The Comic Art of Thomas Rowlandson, The Queen’s Gallery

Skewering the mores of his age, the caricaturist is as much comedian as satirist

“High Spirits” is a multi-layered title: the caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) was himself a heavy gambler and a heavy drinker, continually using up his material assets in such pursuits. His high spirits extended to the Georgian society he satirised with such robust good humour; high society and even low society attracted his interests, while he also expended enormous energy detailing political and sexual intrigues.

So while the 17th century Dutch are busy drinking and eating and being in general enthusiastic consumers in several gorgeous rooms at The Queen’s Gallery, this is a complementary exhibition looking at Hanoverian society a century or more later in the form of 100 vivid prints by Rowlandson. He took on not only the reign of George III, but that of George IV as well. Both monarchs were collectors, the Prince Regent the most assiduous; later even Victoria acquired some Rowlandsons. The Royals have over 1,000 of his prints.

No Gillray nor even a George Cruickshank, Rowlandson is more a comedian than a satirist, but this procession of recognisable characters in all their eccentricities and foibles is fascinating nevertheless. He seems motivated more by affection than by rage. These are not merciless lampoons in a merciless age, and their underlying amiability, even oddly perhaps a kind of sympathy with excess, may explain why the Royals so happily collected his work, even during a time of attempted censorship by the Prince Regent.

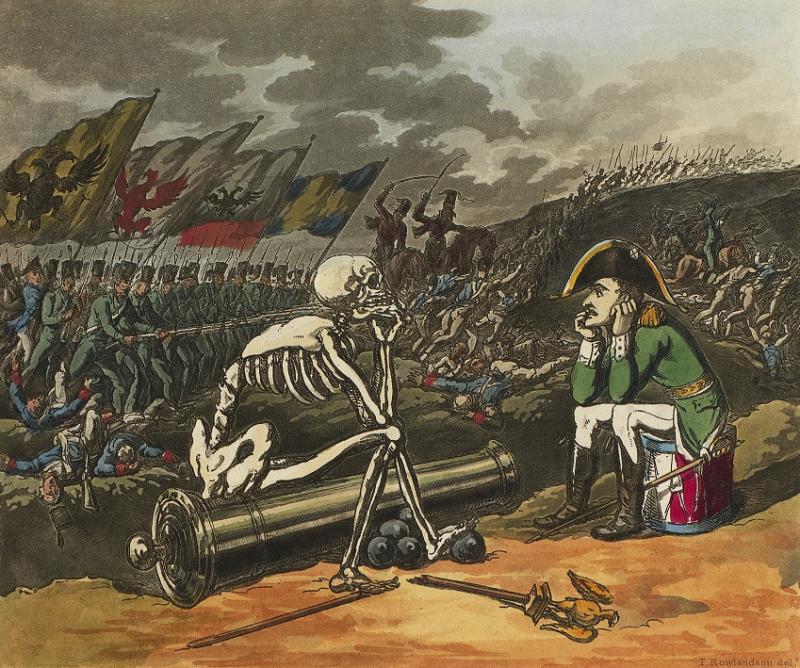

The print-shops flourished in Georgian London, and no stratum of society from the highest to the lowest was spared an appearance; the edginess and anger of some of the leading cartoonists are hardly matched even today. There is something of that when Rowlandson touches on the Napoleonic wars in his most edgy and disturbing image in The Two Kings of Terror, showing Napoleon and Death, as a skeleton, together after the Emperor’s defeat at Leipzig.

Rowlandson had a sophisticated education, including six years at the newly-founded Royal Academy Schools. His gift for draughtsmanship, his clever and rapid response to political and social events, and his lucrative connections with print publishers, imprinted his view of blowsy, self-indulgent men and women – characteristically exaggerated, either obese or emaciated – on the chattering classes, the literati glitterati of the day. Each image can be and is dissected in terms of a wealth of sources and allusions in this detailed exhibition. The upper classes collected the very images that lampooned them – the parallel today might be the readership of Private Eye: they were kept in portfolios, or mounted and hung in print rooms, and even made into so-called decorative scrap screens, of which there is an example in the show (pictured above).

The dissolute Prince Regent and his brothers were natural subjects; the notorious Duchess of Devonshire, wearing a superb feathered hat, in a novel public activity is depicted kissing all-comers – particularly butchers – in exchange for their votes for Charles James Fox, the Whig rival to William Pitt the Younger. And, of course, John Bull turns up.

The dissolute Prince Regent and his brothers were natural subjects; the notorious Duchess of Devonshire, wearing a superb feathered hat, in a novel public activity is depicted kissing all-comers – particularly butchers – in exchange for their votes for Charles James Fox, the Whig rival to William Pitt the Younger. And, of course, John Bull turns up.

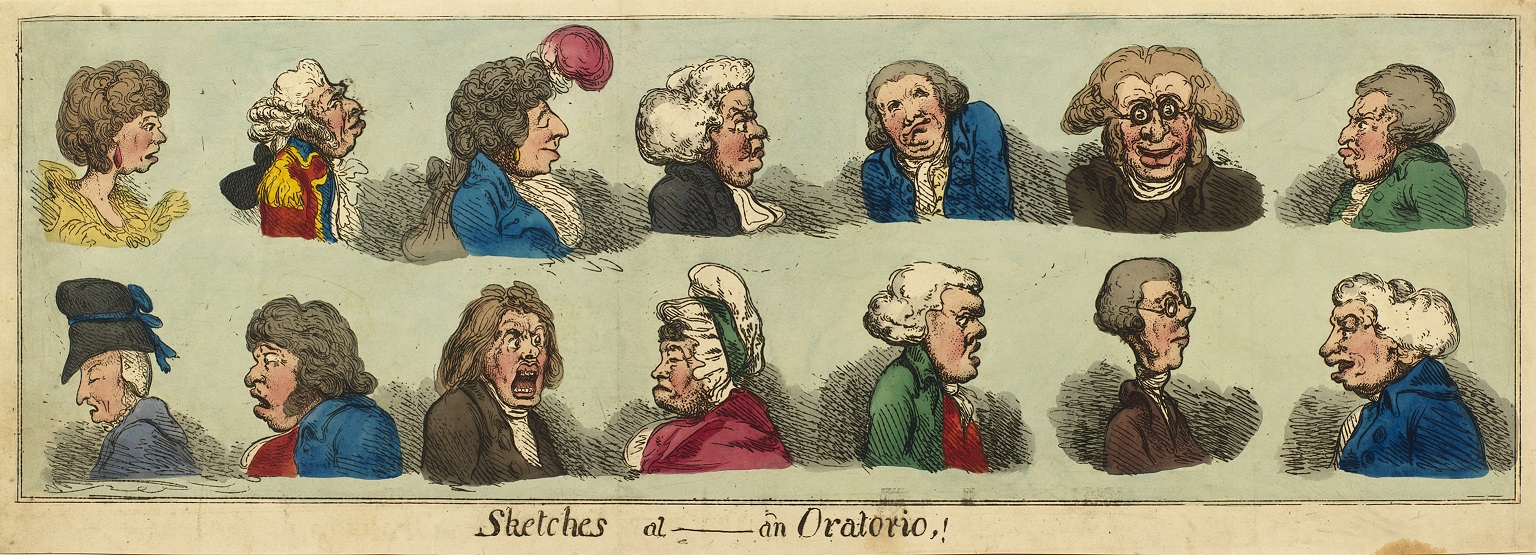

Chaos at the theatre, and the reactions of theatre audiences to comedy and tragedy, not to mention total dismay at having to listen to an oratorio (above, Sketches at - an Oratorio!, 1800), are a rich field. Other favourite subjects include drunks, fashionable dress, and the corruption of characters such as the Duke of York. The Napoleonic wars are inescapable – they extended for 22 years. And Rowlandson was prescient: The New Property Tax Paying His Respects to John Bull, commemorating the extension of the income tax which had been introduced by Pitt to help pay for the war, indicates how the tax will affect the poor far more than the rich.

The whole is a comic fleshed-out history of his day, detailing excess and foolishness in colourful lampoon. Their immediate appeal was necessary for their commercial success and that appeal triumphs over the fact that 250 years later we need detailed captions to appreciate the nuances of Rowlandson’s amiable savagery.

- High Spirits at The Queen’s Gallery until 14 February

Gallery: click on first image to begin

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment