James Ensor? Who he? A marvellous Anglo-Belgian artist (1860-1949) little known outside Belgium, whose masterpiece, The Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889, 1888, is a trophy painting at the Getty, California. It is present here in his own print version, its crowd scene mixing reality and fantasy typical of his wild imagination and extraordinary technical skill.

The overwhelming majority of his paintings, drawings and prints are in private and public collections in Belgium, a country the thought of which makes many people succumb to ennui, despite a rich artistic heritage. Magritte – whose men wear neat bowler hats, Marcel Broodthaers who meditated on eagles as symbols, and now the internationally known Luc Tuymans, whose inspiration as a teenager was indeed James Ensor.

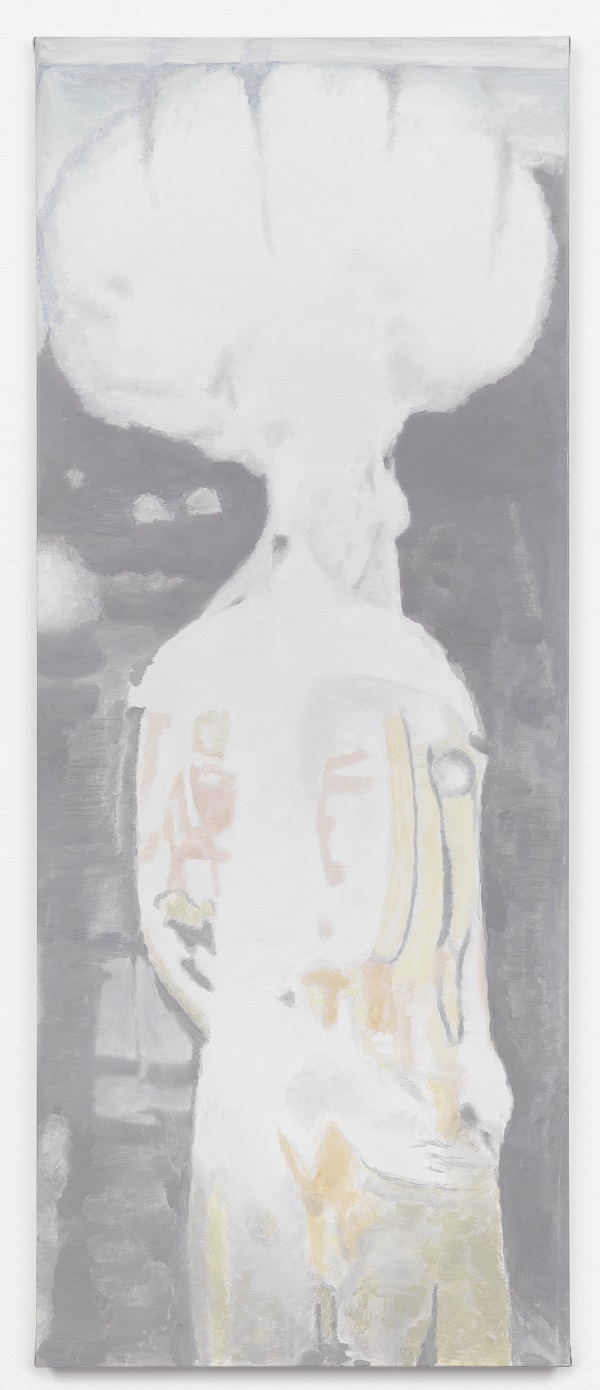

Thus the rather mystifying title for the exhibition which indeed does contain one painting (pictured right: Gilles de Binche, 2004) and one marvellous early print by Tuymans: somehow he has authored as well as curated the show. Yet Tuymans as an artist is not overwhelmed by the fantastical; he plays on shadowy hints at portraits, often using the palest of pastel colours, just whispered imagery. Nor is he playfully in thrall to caricature, as Ensor is. The compilation seems puzzling on two levels: showcasing a mini-retrospective of an artist so little known in this country, filtered through the vision and attitudes of an artist working now – well known to the cognoscenti, but not to the general public. It reminds us that the past never has an objective existence but is always filtered through the varied sensibilities of the present.

Thus the rather mystifying title for the exhibition which indeed does contain one painting (pictured right: Gilles de Binche, 2004) and one marvellous early print by Tuymans: somehow he has authored as well as curated the show. Yet Tuymans as an artist is not overwhelmed by the fantastical; he plays on shadowy hints at portraits, often using the palest of pastel colours, just whispered imagery. Nor is he playfully in thrall to caricature, as Ensor is. The compilation seems puzzling on two levels: showcasing a mini-retrospective of an artist so little known in this country, filtered through the vision and attitudes of an artist working now – well known to the cognoscenti, but not to the general public. It reminds us that the past never has an objective existence but is always filtered through the varied sensibilities of the present.

Here be skeletons, masks, dance of death, angels – not to mention Adam and Eve - hanged men, and grotesquery of all sorts which somehow grew out of his life in Ostend, his obsession with the sea, sea creatures, the beach, the light, and his fantasies. He was hardly backward in coming forward in describing his own achievements: in 1882 Ensor announced that he had shone “the path to all modern discoveries, the influence of light and the liberation of the eyes”. He was a surrealist avant la lettre: “reason is the enemy of art. Artists dominated by reason lose all feeling…” He described the masks that feature in so much of his imagery as “suffering, scandalised, insolent, cruel, malicious” and, depending on the translator, “extravagant, wild, turbulent, exquisite”. And he told Albert Einstein no less, that his subject was the portrayal of “nothing”, an inconceivable notion, we imagine, to the physicist.

Except for three years studying at the Fine Art Academy in Brussels, Ensor lived in Ostend all his life. His Belgian mother had a successful curio and souvenir shop, selling dolls and carnival masks in the seaside resort. Its stock was directly inspirational to the artist and Ensor dragged its chaos for inspiration – cats, a monkey, parrots knocking over the stock of chinoiserie, toys and those carnival masks.

His most productive and original period was the 1880s and 1890s, the dates which comprise the material on view. His view of his world may have been constrained geographically but it was full of provocative contradictions: the tumult of social classes at play and work on the beach, the release of carnival time, the claustrophobic respectability of the haute bourgeoisie. His art remains shocking, surprising and sui generis. There is a marvellous trio of self-portraits; in one, Self Portrait with Flowered Hat, 1883 (pictured below left), the young Ensor wears an enquiring expression and an absurdly yet gracefully decorated hat, its plumes caressing his head and shoulders.

Ensor was involved not only in playing the part of the artist, but in organising Ostend’s celebrations and carnivals, distinguished by costumes and masks. The heart of the exhibition is Intrigue, 1890 (main picture), a frieze of masked and puzzling figures, its centre a hideous couple, with a masked woman in green and her top-hatted companion in a gold cloak; next to them a woman whose plump face wears no mask, holds a baby-like doll. All, including a figure with a skeletal face, are looking out with wide-eyed, frozen expressions at some event we cannot see: the mood seems despairing. We are told this is but a carnival game, with masked revellers moving from pub to pub, guessing each other’s identity. To the uninitiated it appears a fearful crowd of fools about to be engulfed by a fateful horror.

Ensor was involved not only in playing the part of the artist, but in organising Ostend’s celebrations and carnivals, distinguished by costumes and masks. The heart of the exhibition is Intrigue, 1890 (main picture), a frieze of masked and puzzling figures, its centre a hideous couple, with a masked woman in green and her top-hatted companion in a gold cloak; next to them a woman whose plump face wears no mask, holds a baby-like doll. All, including a figure with a skeletal face, are looking out with wide-eyed, frozen expressions at some event we cannot see: the mood seems despairing. We are told this is but a carnival game, with masked revellers moving from pub to pub, guessing each other’s identity. To the uninitiated it appears a fearful crowd of fools about to be engulfed by a fateful horror.

Mortality is ever present; he shows himself as The Skeleton Painter, 1896/7, in his studio surrounded by paintings of all shapes and sizes, not to mention masks – or people. He was a superb draughtsman, turning his attention to macabre caricature and cartoon, dances of death, with cackling skeletons; but there is also a profoundly affecting drawing of his mother on her deathbed, the open mouth already sinking into oblivion, her hands frozen round a cross. A photograph in the catalogue showed he painted her too, and kept this deeply affecting image on the wall of his living room. The 20th century saw honours, titles, professional success and decades of pictorial repetition, playing on the frenzied inventions of his younger self.

Shown in exemplary fashion, this is an intense exhibition, as discomforting and disturbing as it is skilled. There are moments of striking luminosity – he is thought to have admired Turner – most notably in Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise, 1887, the pair fleeing through the Belgian countryside, the sky ablaze with divine fire. The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1889, is darker, pulsating with energy, a huge scrawl of ruffled, crumbling colours. It is fitting perhaps that it has opened in trick-or-treat season, when things go whirring in the night: the subjects are full of trickery, the artist’s skills a treat.

- Intrigue: James Ensor by Luc Tuymans at the Royal Academy until 29 January 2017

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment