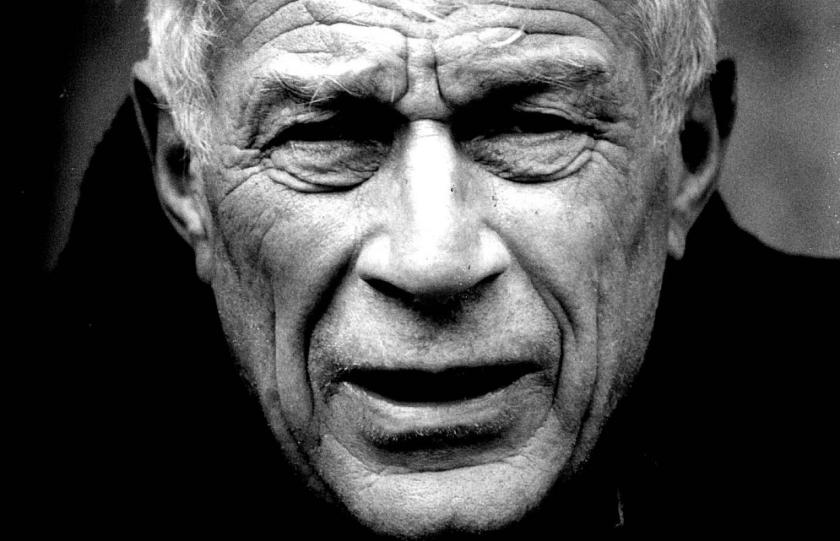

It’s hardly the lot of an art critic to be loved and admired, still less to speak to an audience that might reasonably be called “the public”. And how many will find their ideas still current 40 years on? All of these things can be said for John Berger, who has died aged 90, a man whose radical approach to looking at art was an absolute inspiration, and whose ideas were a solid presence in my childhood, woven into my early memories as surely as the pages of a photo album.

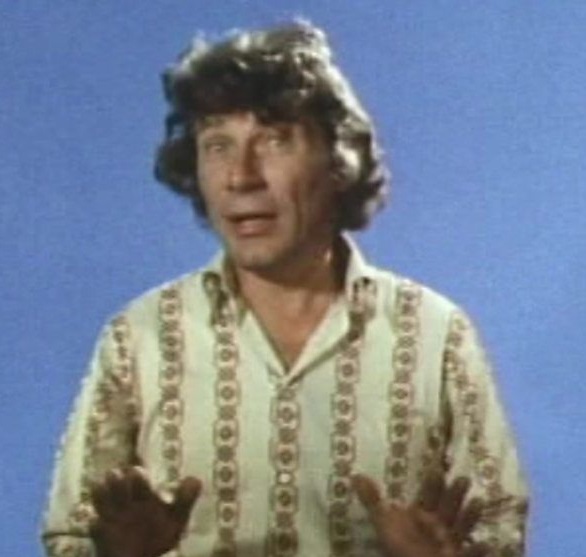

A committed Marxist, Berger set out as a painter, and his writings range from novels, to essays to poetry. He won the Booker Prize for his 1972 novel G, giving half of the prize money to the Black Panthers in protest at the prize's origins in the slave trade. To call Berger an art critic is to tell just a part of his story, but there is no doubt that he will best be remembered for Ways of Seeing (pictured below), the groundbreaking TV series aired in 1972 that railed against art as the rarefied and ultimately irrelevant preserve of the upper classes. But in pointing out the ways in which art had been used to define and delineate the powerful and subjugate the weak, perhaps most memorably in his analysis of the depiction of the female body, Berger’s view of art was as a resolutely living thing, that could and did belong to us all.

For the generations of art history students too young to have seen Ways of Seeing on TV, the book accompanying the series became a touchstone and, surely uniquely, it is a piece of critical theory that not only feels worth referring back to regularly but makes perfectly agreeable bedtime reading.

For the generations of art history students too young to have seen Ways of Seeing on TV, the book accompanying the series became a touchstone and, surely uniquely, it is a piece of critical theory that not only feels worth referring back to regularly but makes perfectly agreeable bedtime reading.

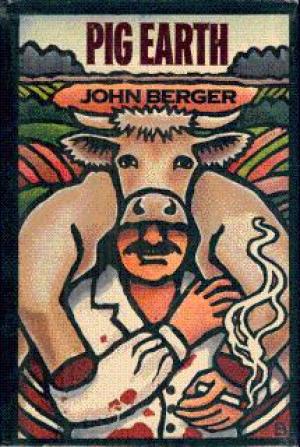

Even so, for all the impact of this book, along with other notable writings like Art and Revolution (1969), which in relating the career of Russian sculptor Ernst Neizvestny made the case for the continued role of art in society, it is Berger’s trilogy Into Their Labours that for me was unexpectedly formative. Through essays, poetry and fiction, Berger explores peasant life, shaped by his experiences of moving with his family to live and work in one of the last traditional peasant communities in France. It is a harsh and unenviable existence that Berger celebrates and analyses with tenderness but without sentimentality – a feat in itself, you might say: certainly, it is hard to imagine embarking on a similar project today. Berger's Introduction to the first volume, Pig Earth (1979), a battered copy of which served as a sort of manifesto for life for my parents in the late 1980s, claims that “this trilogy has been written in a spirit of solidarity with the so-called 'backward'", a claim which would probably meet with shrieks of derision if attempted now.

But while Pig Earth and the two volumes that followed ought to feel, perhaps principally due to their Marxist politics, rather dated, the ideas they explore and the sense they give of a writer – an artist – at work have lasting, and even increasing, currency. They stand as the most sensitive and frank of portraits, exploring life's great themes and, perhaps most fundamentally, the trauma of change. But on one level, they show very simply what it is like to be an artist, the way an artist must look at his or her subject, the negotiations that an artist must make.

But while Pig Earth and the two volumes that followed ought to feel, perhaps principally due to their Marxist politics, rather dated, the ideas they explore and the sense they give of a writer – an artist – at work have lasting, and even increasing, currency. They stand as the most sensitive and frank of portraits, exploring life's great themes and, perhaps most fundamentally, the trauma of change. But on one level, they show very simply what it is like to be an artist, the way an artist must look at his or her subject, the negotiations that an artist must make.

His absolute belief in the value and power of art is at the heart of his legacy, and his ideas about art as carrier of ideology, to be read in context have completely permeated mainstream thinking about art, shaping the way that exhibitions are themed and TV series written. It is not an uncontroversial legacy though, and many would argue that the academic art history has become overly preoccupied with social and historical context, the decline of now largely discredited connoisseurial skills having left art historians with dangerously little expertise when it comes to identifying the work of individual artists.

And yet for all his interest in context, Berger can never be said to have reduced the study of art to the marshalling of ideas. As a painter himself, he had an innate understanding of the artist's agenda, and by showing the ways in which art has carried meaning, Berger opened our eyes to the timeless power of images, in art, in advertising, and now more than ever, in social media.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment