From India, here is a hoard of what really looks like treasure, much of it emerging into the light of day after decades, if not a century. Jewellery, sculpture, textiles, paintings, carvings, architectural fragments, domestic interiors, metalwork, drawings, books, furniture, toys, photographs, plasterwork – all are gathered together in a glittering display in galleries unified under the name of Lockwood Kipling.

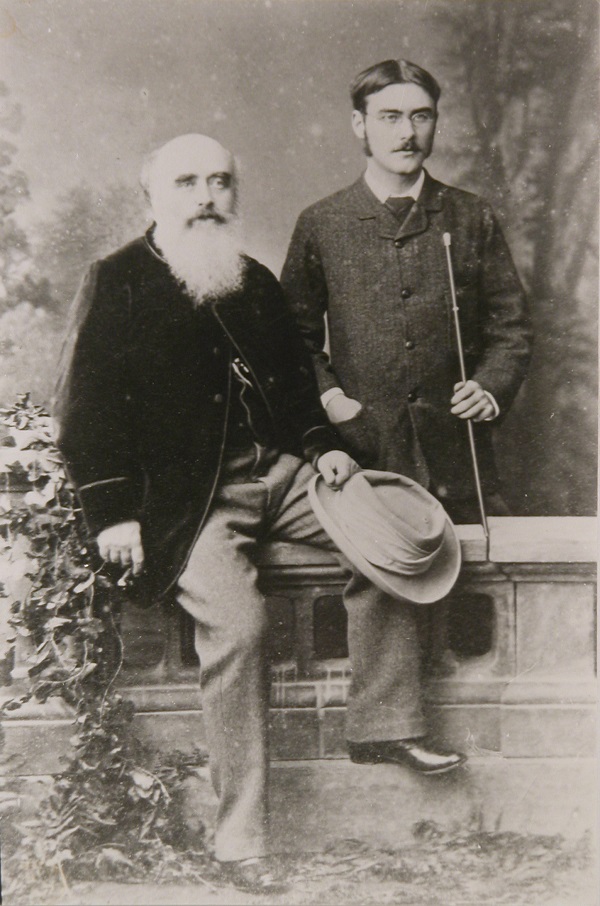

Who was he – other than an evocative name seemingly out of Trollope or Dickens? John Lockwood Kipling (1837-1911) is far better known as the father of Rudyard, than as a pioneering polymath: artist, scholar, teacher, journalist, curator, designer, civil servant and influential bridge between two very different cultures (Pictured below right: Lockwood Kipling with his son Rudyard Kipling, 1882). Charismatic, charming, persuasive, energetic and widely travelled, this son (the eldest of six) of a Methodist minister is a marvellous exemplar of the imagination and idiosyncratic sensibility that characterised the great Victorians.

His remarkable biography tells us that he was inspired as a teenager by a visit to the Great Exhibition of 1851, affected in particular by the amazing displays in the India Courts. Indeed, organised and led by Prince Albert among others, the Great Exhibition was the catalyst for the foundation of the South Kensington museums and has a claim to be the greatest temporary museum and trade fair yet created.

His remarkable biography tells us that he was inspired as a teenager by a visit to the Great Exhibition of 1851, affected in particular by the amazing displays in the India Courts. Indeed, organised and led by Prince Albert among others, the Great Exhibition was the catalyst for the foundation of the South Kensington museums and has a claim to be the greatest temporary museum and trade fair yet created.

This exhibition has a wonderful cluster of glowingly detailed watercolour depictions of the Great Exhibition, complete with model elephants, in the Crystal Palace by Joseph Nash, Henry Clark Pidgeon, Walter Goodall and others. Significant purchases were made for the embryonic South Kensington Museum, a prelude to the material that Lockwood Kipling was to send back during his Indian sojourn.

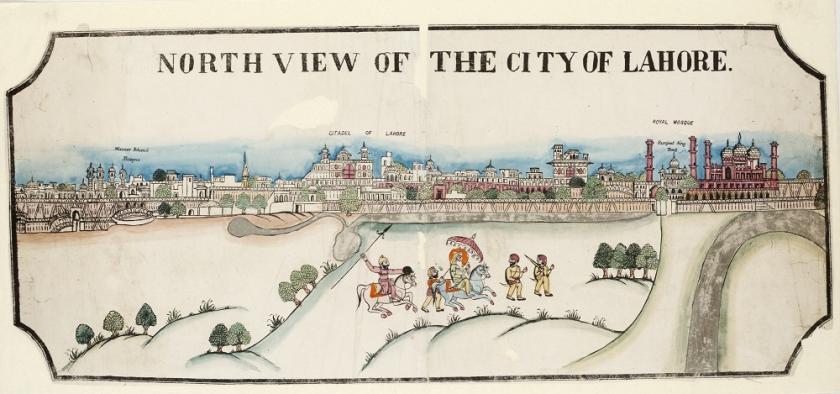

After that fateful visit to the Great Exhibition, Kipling studied and worked in the Potteries, notably in Stoke-on-Trent, then joined the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) to work on decorations, terracottas and mosaics still extant on the building. Inspired by those early impressions of Indian arts and crafts achievements he went on to work as the director of art schools and museums in Bombay and Lahore (1865-1893). He was a crucial link between teaching establishments and artists and designers in England, and their counterparts in India. A bout of typhoid in 1875 turned him into an old man in looks, but it was almost 20 years later that ill health led to the family’s eventual retirement back in England. But he went on to collaborate with an Indian colleague to create the Durbar Hall for Queen Victoria at Osborne House, and the Indian billiard room for the Duke of Connaught at Bagshot, and to illustrate his son’s books.

Lockwood Kipling had strong views about the worth of Indian arts and crafts, and spent three decades attempting to ensure the survival of the skills of making that he found among the artists of the subcontinent. He plunged into debates about the worth of what he found, argued for the ways in which such making could reach commercial viability, and supported Indian arts and crafts in more than a score of the International Expositions that were such a feature from the later 19th century on.

Lockwood Kipling had strong views about the worth of Indian arts and crafts, and spent three decades attempting to ensure the survival of the skills of making that he found among the artists of the subcontinent. He plunged into debates about the worth of what he found, argued for the ways in which such making could reach commercial viability, and supported Indian arts and crafts in more than a score of the International Expositions that were such a feature from the later 19th century on.

This profusion of Indian art, the jewellery all a-glitter, the inlaid boxes superbly crafted, makes for the visible reflection of an impressive, profoundly energetic, imaginative and intelligent career (pictured above left: Wedding chest, c.1888). This selection of material sent back from India was propelled by conviction and admiration for the craftsmanship, ingenuity and visual talent abounding in the culture in which Kipling found himself.

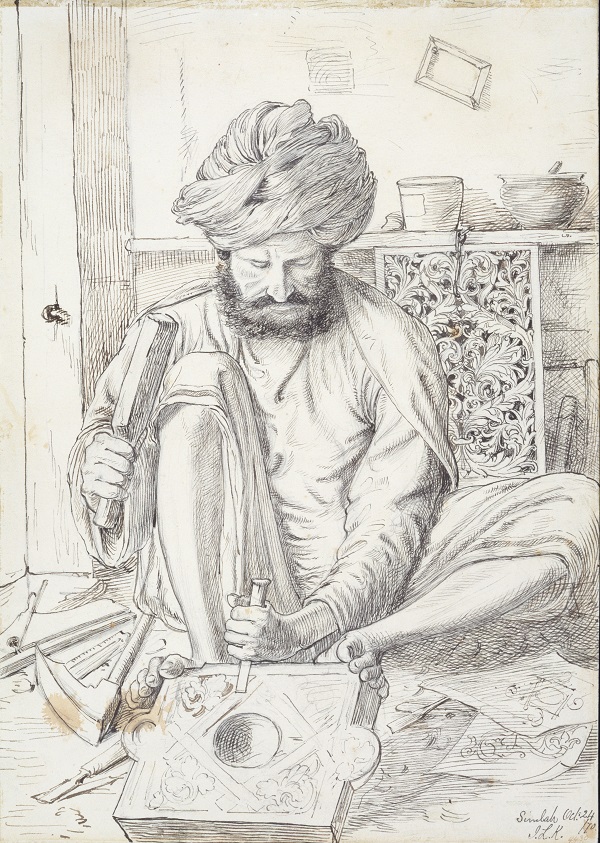

Interspersed are Victorian portraits of the leading characters in this enthralling narrative, including Millais’s portrait of Lord Lytton, 1876, poet, aesthete, diplomat and Viceroy of India; films of the buildings of Mumbai and Lahore where Kipling directed art schools and museums for nearly 30 years (1865-1893); photographs of Kipling and his family – his wife Alice Macdonald, herself an artist from a family of artists, and their children Rudyard and Trix – and their homes in India. There is an affecting series of scrupulous and tender drawings of Indian craftsmen at work by Kipling (pictured right) and a film of contemporary craftsmen at work today.

Interspersed are Victorian portraits of the leading characters in this enthralling narrative, including Millais’s portrait of Lord Lytton, 1876, poet, aesthete, diplomat and Viceroy of India; films of the buildings of Mumbai and Lahore where Kipling directed art schools and museums for nearly 30 years (1865-1893); photographs of Kipling and his family – his wife Alice Macdonald, herself an artist from a family of artists, and their children Rudyard and Trix – and their homes in India. There is an affecting series of scrupulous and tender drawings of Indian craftsmen at work by Kipling (pictured right) and a film of contemporary craftsmen at work today.

All is linked by an examination of Kipling’s own art: the terracotta and sculptural ornament which decorates the V&A itself, the great Victorian buildings in Bombay, and the beguiling, witty pencil portraits and illustrations which flowed from his pen. His ability to design extended into many different areas; for the 1877 Delhi Durbar which marked the designation of Queen Victoria as Empress of India, he designed some 70 banners for the Princes and Maharajahs, not to mention the banner for Lord Lytton himself.

This multi-layered display shows us several things: how one culture studies another, shifting attitudes towards colonialism and imperialism, differing conversations about material culture, why we collect objects and why we should. A great gallery is a three-dimensional collection of things which when properly examined, interrogated and investigated show us the shifting histories of our past and present, and so it is here.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment