Drifting, floating, running, crowding: all these feelings of movement and stasis apply in a mesmerising selection of scenes, imagined and observed over 40 years by a true original. Michael Andrews (1928-1995), born and brought up in Norwich, studied at the Slade School during a golden period. His teachers included William Coldstream and Lucian Freud, and a highly individual cohort of fellow students who were to inhabit the heart of the art world, from Paula Rego to Craigie Aitchison. Quiet and shy, Andrews nevertheless easily inhabited the Soho art scene, especially Soho’s Colony Room, its denizens including Francis Bacon.

A cluster of paintings from the 1950s and 1960s under the rubric "people at play" show individual portraits which have a striking sense of immediacy; party scenes and people sprawling in a garden as in Late Evening on a Summer Day, 1957, have a sense of suppressed exhilaration. You can visualise easily that Andrews’s people speak – and have something to say even perhaps things you may not want to hear – or are meant to hear. Andrews’ people are seriously playful, or playfully serious – in any event curiously real.

In the 1970s a truly remarkable group was called Lights, and several have been brought together again here. Lights VII: A Shadow, 1974 (pictured right), is haunting: a huge balloon’s shadow drifts over a vast vista of land, sea and sky; the silhouette of its passenger basket does not tell us if there is any occupant, or how many, or what the journey portends. By now Andrews had moved on to using acrylic, but he was able to somehow deploy the kind of subtle layering that can be so characteristic of oils.

In the 1970s a truly remarkable group was called Lights, and several have been brought together again here. Lights VII: A Shadow, 1974 (pictured right), is haunting: a huge balloon’s shadow drifts over a vast vista of land, sea and sky; the silhouette of its passenger basket does not tell us if there is any occupant, or how many, or what the journey portends. By now Andrews had moved on to using acrylic, but he was able to somehow deploy the kind of subtle layering that can be so characteristic of oils.

Lights III: The Black Balloon, 1973, has its protagonist floating over an urban river, reflections of city lights are caught on the water and the bridge over the river gives the image a strong horizontal. Study for Lights V: The Pier Pavilion, 1973, is just that: a built-up pier jutting out to sea, the blues of water and sky melding. These are dreamlike images, open to whatever significance the viewer lends them, meditations on freedom – and restraint, earthbound but with the promise of limitless sky.

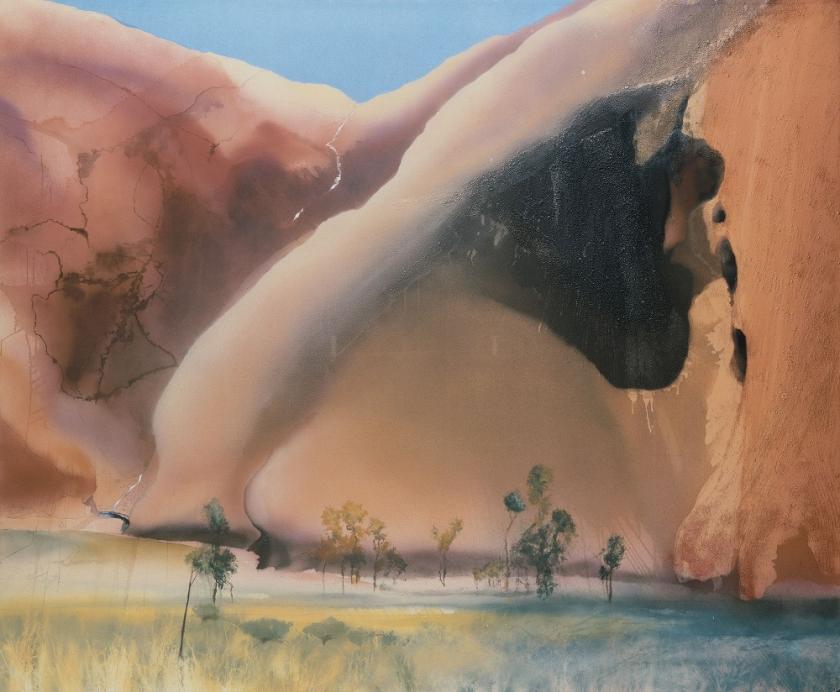

In the 1980s a visit to Australia resulted in a sequence of big paintings portraying one of the world’s best-loved and profoundly mysterious phenomena, Ayers Rock, sacred Uluru to the Aborigines. This huge edifice, rising to its height from a great plain, curved, riven with cracks, naturally gives itself to manifold interpretations. The reddish rock glowing in the implacable sunlight and occasional storm is seemingly some kind of divine manifestation, and Andrews’ paintings and watercolours capture something of the rock’s overwhelming presence.

The spectrum he turned his attention to included what seems an improbable attachment to deerstalking on the Scottish moors; swimming with his daughter in a black pool; schools of fish in all their fantastical shapes and formations. Both his draughtsmanship and his skill with watercolour are well displayed, from portraits to landscape studies.

The last few paintings are heartbreaking Here sweeps of colour and grit melded together coalesce to varied views of the Thames estuary, taken from varied vantage points People and structures are suggested, and the ebb and flow of the tidal river. The Thames at Low Tide, 1993-1994, and Thames Painting: The Estuary, 1994-1995 (pictured left), are among his last several paintings. Somehow he conveyed in greys, blacks, pale blues, mini explosions of muted colour, an intimation of mortality evident in the play between a kind of melancholy and a kind of joy. These are sweeping views, which clearly suggest cycles of movement and change, familiarity – a domesticated river – and vertiginous danger.

The last few paintings are heartbreaking Here sweeps of colour and grit melded together coalesce to varied views of the Thames estuary, taken from varied vantage points People and structures are suggested, and the ebb and flow of the tidal river. The Thames at Low Tide, 1993-1994, and Thames Painting: The Estuary, 1994-1995 (pictured left), are among his last several paintings. Somehow he conveyed in greys, blacks, pale blues, mini explosions of muted colour, an intimation of mortality evident in the play between a kind of melancholy and a kind of joy. These are sweeping views, which clearly suggest cycles of movement and change, familiarity – a domesticated river – and vertiginous danger.

A new old master of modern art has been revealed, showing that painting far from being a dying medium is still capable of magnificence. In Andrews’ case although everything is recognisable he manages even from the ordinary, the quotidian, and occasionally the transcendent, an individual beauty, illuminating and surprising. This least celebrated artist of the so-called London School did have the requisite major exhibitions – Tate, Hayward, Whitechapel – and prestigious, even grand gallery representation, from the Beaux Arts to Marlborough to Anthony d’Offay. His work is not only in some of the finest public collections, but also collected by the most discerning of private connoisseurs. So why is he not as well known as, say, Auerbach, Kossoff, Freud? It is true that he was a very slow worker, thinking, revising, often postponing shows, and in financial difficulties because he did not keep up with demand, and he died relatively young. But it is still a mystery that work of this stature and memorability is relatively uncelebrated. But here is a chance to see these marvellous depictions in optimum conditions – huge galleries, lots of space, daylight – at Gagosian’s new Caruso St John building in Grosvenor Hill.

- Michael Andrews: Earth Air Water at Gagosian Grosvenor Hill until 25 March

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment