A photograph from 1858 shows a feeble and frail octogenarian who happens to be the last Mughal emperor. Bahadur Shah II (pictured below right), reclining in his wretched prison in Delhi, awaiting trial, is about to be exiled to Burma. Many of his family and his retinue would be summarily executed, the civilian population murdered, and a number of the great Mughal monuments of Old Delhi ruined. The British were on the rampage, finally quelling the 1857 Indian mutiny which had spread through the sub-continent. It was both a tragic and a pathetic ending to one of the greatest dynasties the world has seen: 15 emperors who had held sway over much of the Indian subcontinent.

That dynasty is celebrated in this treasure trove of an exhibition, featuring illustrated manuscripts from the three-plus centuries– 1526-1858 – of the Mughal emperors’ reign. Here are leaves from albums of histories, portraits, narratives, poems, biographies, epics, cookbooks, domestic manuals, as well as paintings of palaces, cities and villages, painted parades of fantastical and opulent durbars, and a 15-foot panorama of Delhi as the city was in 1846. There are also several Korans. Objects indicating the grandeur of the Mughal’s material wealth include a Mughal crown (see gallery overleaf), a giant jade tortoise, a suit of 17th-century Mughal armour and a jewelled flywhisk.

By the beginning of the 18th century Aurangzeb, the sixth Emperor, ruled over probably one fourth of the world’s population: 150 million people. After this apotheosis, the empire declined, the Mughals were confined to ever more ceremonial roles while the East India Company and then the British ruled, until the final catastrophe extinguished the dynasty. What is left is a magnificent array of art, Persian miniatures in bejewelled colours, commemorating and recording life at court, battles, the hunt, flora and fauna, and endless portraits of courtiers, aristocrats, mistresses, wives and the emperors themselves.

By the beginning of the 18th century Aurangzeb, the sixth Emperor, ruled over probably one fourth of the world’s population: 150 million people. After this apotheosis, the empire declined, the Mughals were confined to ever more ceremonial roles while the East India Company and then the British ruled, until the final catastrophe extinguished the dynasty. What is left is a magnificent array of art, Persian miniatures in bejewelled colours, commemorating and recording life at court, battles, the hunt, flora and fauna, and endless portraits of courtiers, aristocrats, mistresses, wives and the emperors themselves.

The Mughals came from Central Asia, via Afghanistan, and were proud to claim descent from Genghis Khan and Timur the Lame, aka Tamerlane; they were in varying degrees fervent admirers of Persian culture, much of which they imported to their Indian dominions. Under the first emperor Babur, Persian became the spoken and written language of choice, and practically all the Mughals were united in their admiration of Persian culture, not to mention gardens and building styles.

Their personal history was marked by continual strife, addiction to opium and alcohol, and general family chaos as the imperial succession was fought over. The fifth Emperor Shah Jehan, the builder of the Taj Mahal, was incarcerated for the last eight years of his life by his successor, his second son Aurangzeb. He could look out from his prison at the great building which commemorated his love for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died after giving birth to their 14th child.

Their personal history was marked by continual strife, addiction to opium and alcohol, and general family chaos as the imperial succession was fought over. The fifth Emperor Shah Jehan, the builder of the Taj Mahal, was incarcerated for the last eight years of his life by his successor, his second son Aurangzeb. He could look out from his prison at the great building which commemorated his love for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died after giving birth to their 14th child.

Much of this show features the Indian equivalent of our own illuminated manuscripts, distinguished by the beautifully cursive varieties of Arab script, and illustrated by teams of court artists many imported from Iran and of diverse backgrounds - Muslim and even Hindu. The number of craftsmen and artists expanded exponentially during the long reign of Akbar, the illiterate emperor who loved stories, amassed a library of 24,000 volumes and commissioned a huge number of paintings; he declared that he could not tolerate those who made the slightest criticism of art. “A painter is better than most in gaining a knowledge of God,” he declared, for although the artist can draw and depict, he understands that it is only the divine that can bring life. The Muslim Akbar was highly unusual in not only devising eclectic religious practices for himself but in tolerating all, from Jain to Hindu, Parsee to Christian.

See Mughal India gallery overleaf

Akbar commissioned the illustrations for various manuscripts of a Persian translation of the autobiography of his grandfather Babur, who in colourful and complex array hunts deer and fights battles (pictured on previous page, Battle of Panipat). Akbar also ordered his own history to be written: we see the infant Akbar being placed into the arms of one of the grandly born ladies of the harem who acted as wet nurses; one of the most vivid illustrations of his life shows Akbar’s vision in which he gave up hunting and ordered all the terrified animals to be freed. It was just as important to follow the genealogy of the emperor, so this same manuscript shows Babur, Akbar’s grandfather, making his son Humayun his successor. A host of men richly robed but all wearing white turbans are witness to the passing of the succession; all takes place in a gorgeous pavilion, its floor a vividly flowered carpet, and a host of drummers punctuates the proceedings.

Akbar commissioned the illustrations for various manuscripts of a Persian translation of the autobiography of his grandfather Babur, who in colourful and complex array hunts deer and fights battles (pictured on previous page, Battle of Panipat). Akbar also ordered his own history to be written: we see the infant Akbar being placed into the arms of one of the grandly born ladies of the harem who acted as wet nurses; one of the most vivid illustrations of his life shows Akbar’s vision in which he gave up hunting and ordered all the terrified animals to be freed. It was just as important to follow the genealogy of the emperor, so this same manuscript shows Babur, Akbar’s grandfather, making his son Humayun his successor. A host of men richly robed but all wearing white turbans are witness to the passing of the succession; all takes place in a gorgeous pavilion, its floor a vividly flowered carpet, and a host of drummers punctuates the proceedings.

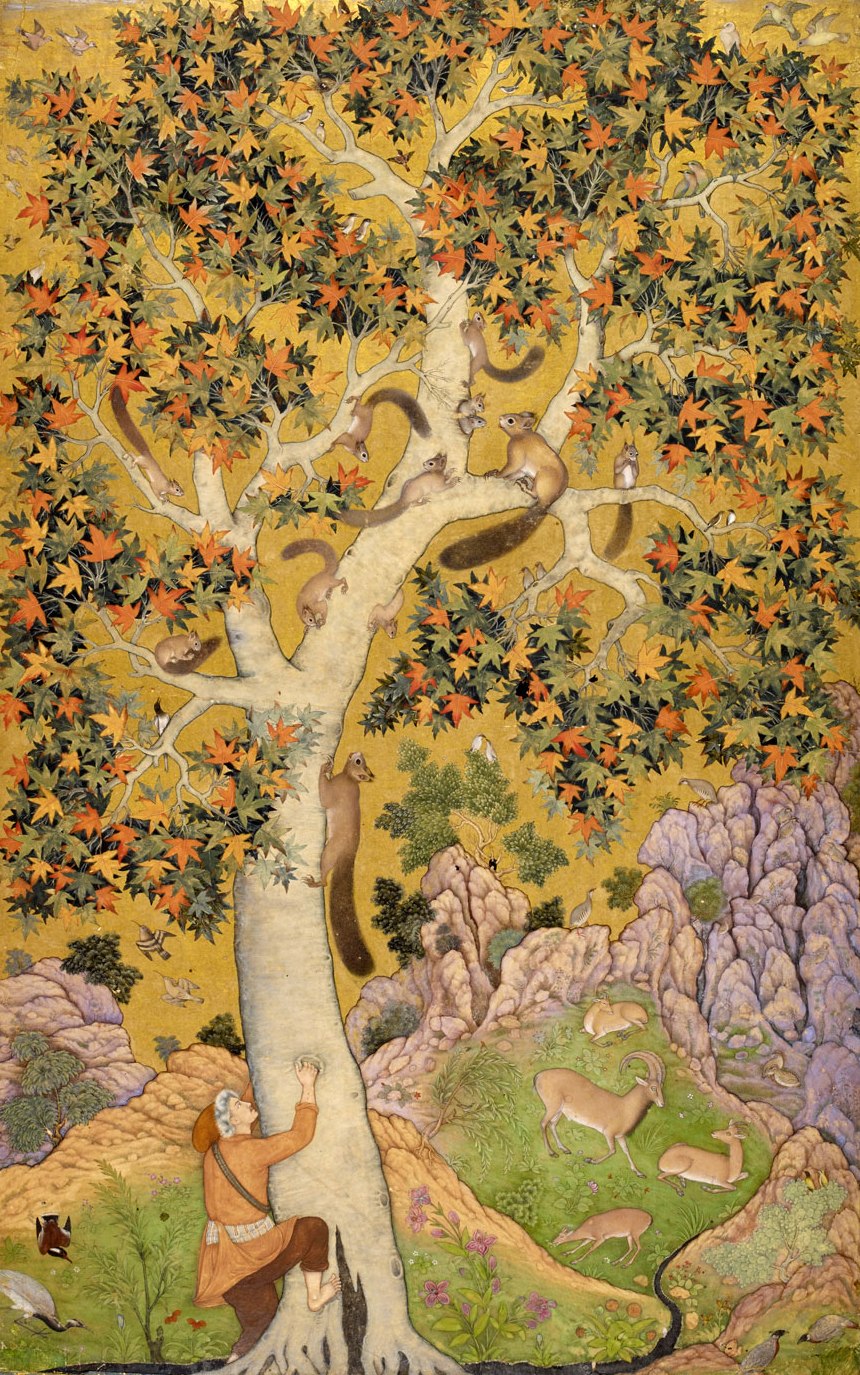

A page from an album compiled in Jahangir’s reign – Akbar’s successor – featuring squirrels, rocks, flowers, goats and birds (pictured above right) suggest that there was as much detailed observation of nature as meticulous rendering of historic events, portraits of courtiers and rulers, or epic encounters between fictional characters.

This rare anthology brings into the light a selection from the fabulous collections of the British Library, culled from the Old India Office and the British Museum: it affords a glimpse, however fragmented, into the fabled life of the Mughal courts and through several hundred artifacts, and makes their history visible.

- Mughal India: Art, Culture and Empire at the British Library until 2 April 2013

Click on the gallery images to enlarge

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment