In the video, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner smiles shyly before beginning. As she speaks, her voice gains conviction, momentum, power. Her poem tells of the Marshall Islands inhabitants, a “proud people toasted dark brown”, and a constellation of islands dropped from a giant’s basket to root in the ocean. She describes “papaya golden sunsets”, “skies uncluttered”, and the ocean itself, “terrifying and regal”. She tells of “songs late into the night” and “a crown of fuchsia flowers encircling / aunty Mary’s white sea foam hair”. In a room dominated by a vast appliqué textile of blue tarpaulin slashed in chevrons and falling from the ceiling in glinting waves (Kiko Moana by Mata Aho Collective), her words conjure an enchanted and endangered way of life, fatefully entwined with the ocean. “Tell them what it’s like / to see the entire ocean level with the land,” she says.

The exhibition is divided thematically. Sections cover navigation, deities, gifts, houses and ceremonies. Each sheds light on the extraordinary variety of artistic, spiritual and social expression present on the thousands of islands that make up Oceania. It examines the way Pacific Islanders formulated relationships through established hierarchies and gift-giving, and how contact with Europeans complicated these and left a complex legacy.

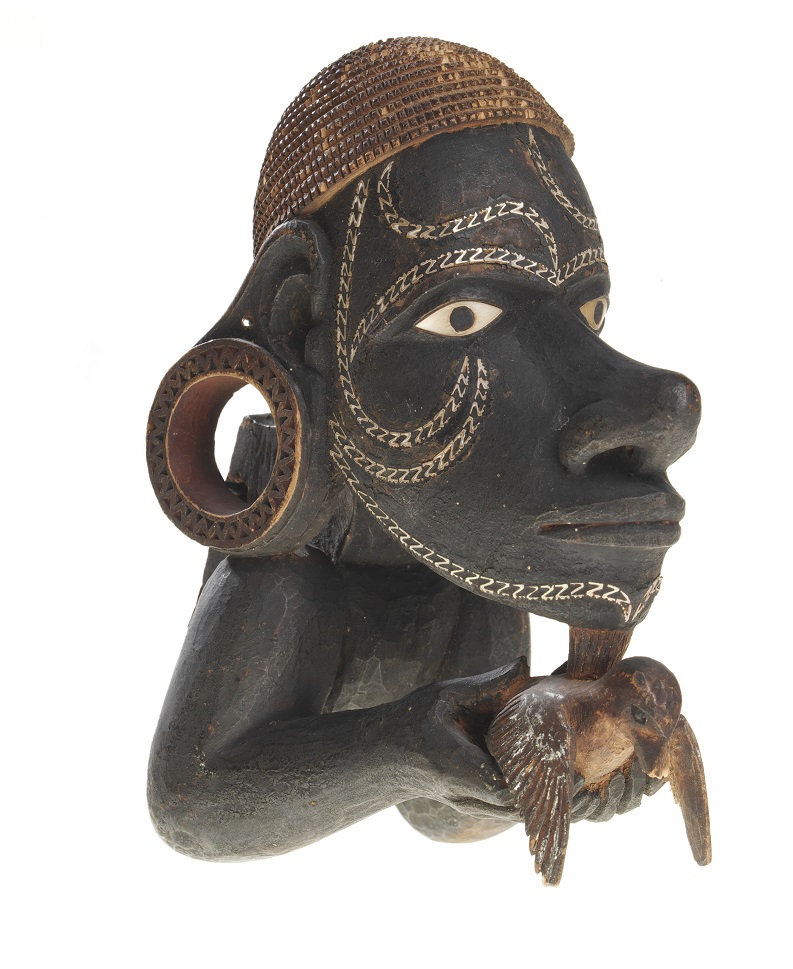

Connection with the sea continues in the following room. Stunning matrixes of wood, cane and shell are navigation charts which track the movement of stars, tides and animals. A highly decorated bonito fishing boat is displayed next to a Wuramon, or soul canoe, used in initiation ceremonies and funerals by the Asmat people of West Papua. A Nguzunguzu canoe prow (pictured left) from the Solomon Islands bears a pigeon, symbolic of navigational prowess, and bestows protection on its crew who would have been paddling towards war. Other prows are shaped as crocodiles, birds and people.

Connection with the sea continues in the following room. Stunning matrixes of wood, cane and shell are navigation charts which track the movement of stars, tides and animals. A highly decorated bonito fishing boat is displayed next to a Wuramon, or soul canoe, used in initiation ceremonies and funerals by the Asmat people of West Papua. A Nguzunguzu canoe prow (pictured left) from the Solomon Islands bears a pigeon, symbolic of navigational prowess, and bestows protection on its crew who would have been paddling towards war. Other prows are shaped as crocodiles, birds and people.

Pieces on display range from contemporary artworks to pieces collected during Captain Cook’s initial voyage in 1768. Many have been borrowed from ethnographic and anthropological collections across Europe, themselves legacies of old empires – the Musée du quai Branly in Paris, Museum für Völkerkunde in Hamburg, the Pitt Rivers in Oxford, the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge. Others have come from New Zealand – the Auckland War Memorial Museum, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington, the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Contact with Europeans corroded Island societies, spreading disease, encouraging raids and disturbing established power relations – a terrible legacy addressed in Lisa Reihana's panoramic video In Pursuit of Venus [infected] – yet Pacific Islanders also sought to shape these relationships through ceremonies and lavish gifts while also embrancing Christianity.

A red and yellow ‘Ahu’ula feather cloak (main picture) tells tragically of these fraught relations. It belonged to King Kamehameha II – the flamboyant Hawaiian monarch who abolished the strict kapu system of traditional laws governing behaviour, food and clothing – who travelled to England with his wife and half-sister Queen Kamāmalu. The lavish gift was intended for George IV both as a mark of esteem (red feathers symbolise royalty) and a means of establishing diplomatic relations with a large imperial power. Yet before Kamehameha and Kamāmalu could meet the English monarch, both contracted measles, to which they had no resistance, and died shortly after.

Misinterpretations as well as disease sullied relations. The distinctive bent-kneed stance of a Māori Madonna and Child recalls other Island deities – such as Kū and Lono, the Hawaiian gods of war and peace – and a pair of male and female figures from Papua New Guinea. The Madonna’s face is marked with a tā moko, a tattoo usually reserved for men of high rank and a mark of deep respect. The marking ceremony could only be carried out by tohunga tā moko experts with uhi bird bone chisels, and the design was determined by rank, ancestry and social prestige. While the statue is a clear bridge between cultures which indicates the extent to which Christianity was absorbed by Islanders, the figure was quite likely rejected by a Catholic priest on the basis that it was offensive. On the other hand, a drawing (pictured below right) by Tuai, a leader of the Māori and one of the first to visit and tour Britain, which depicts his brother’s own tā moko in exquisite detail indicates a level of mutual respect and curiosity between himself and the English missionary and schoolteacher George Seth Bull for whom it was drawn. As one of the two curators Dr Peter Brunt points out, whether on personal or political levels, these were “objects that forged relationships between Islanders and Europeans”, both expressing and cementing relations.

Another relationship, this time between living Islanders and the ancestors, runs through the exhibition – and recurs in both profound and everyday contexts. Fans can be spun to animate the carvings on their handles and an elegant buff flax cloak with a dark brown tāniko border explains how ancestral māna (spiritual power) invests the very weave which links ancestors and descendants together in a pan-temporal conception of whakapapa, or genealogy. A Māori hei tiki – greenstone pendant worn around the neck – might represent a specific deity or be invested with the spirit of an ancestor who can thereby remain close to their descendent. A sandalwood statue of the Polynesian deity A’a is carved with more than 30 protruding figures and contains a hollow cavity accessed by removing its back. The figure, which represents and is invested with an ancestor’s spirit, can also contain their very bones.

![Tooi [Tuai], Drawing of Korokoro's moko, 1818 © Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries Tooi [Tuai], Drawing of Korokoro's moko, 1818 © Sir George Grey Special Collections, Auckland Libraries](/sites/default/files/images/key%20204.jpg) As with contact between islands and peoples, relationships with the dead were not straightforward. A tusked fish malangan from New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, alludes to the deceased’s place in society by representing certain aspects of kinship and belonging. After a ceremony in honour of the deceased, the intricate malangan would be abandoned, set on fire, sometimes traded or left to decay. The presence of the dead – represented here on the tip of the fish’s tongue – would be finally released: allowing the deceased to finally pass fully into the spirit world being both a propitiation and a dismissal.

As with contact between islands and peoples, relationships with the dead were not straightforward. A tusked fish malangan from New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, alludes to the deceased’s place in society by representing certain aspects of kinship and belonging. After a ceremony in honour of the deceased, the intricate malangan would be abandoned, set on fire, sometimes traded or left to decay. The presence of the dead – represented here on the tip of the fish’s tongue – would be finally released: allowing the deceased to finally pass fully into the spirit world being both a propitiation and a dismissal.

The importance of interaction, ceremony, commemoration and movement is foregrounded. While these pieces speak of the cultures in which they were made, the individual hands that made them, their social purpose and material history, they also act as ambassadors of another, richly detailed spirit world. Extraordinary drawings by the Roviana man, Aqo, for the British anthropologist AM Hocart and the Koita chief Ahuia Ova in response to questions from the British ethnographer Charles Seligman depict demons and myths beside living people and historical battles. Before the installation, traditional blessings were carried out and feathers and leaf coronet offerings placed in front of the pieces. We may understand these extraordinary pieces as objets of art, of craft or as artefacts, but for many Islanders they remain spiritually potent.

What this ravishing show displays most clearly is a constellation of cultures in conversation with themselves, their dead, and the outside, in a constant state of flux and movement. Every piece tells a story and the one criticism that can be levelled at the exhibition is that so few of these stories actually make it to the labels – even the audio guide doesn’t cover each piece. Oceania is a wonderful introduction to the rich and often contradictory art and cultures of the Pacific Islands, which are threatened by rising sea levels. “Tell them that some of us / are old fishermen who believe that God / made us a promise / some of us / are more skeptical of God,” says Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner. One thing though is certain – “we / are nothing without our islands.”

- Oceania at the Royal Academy to 10 December

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)