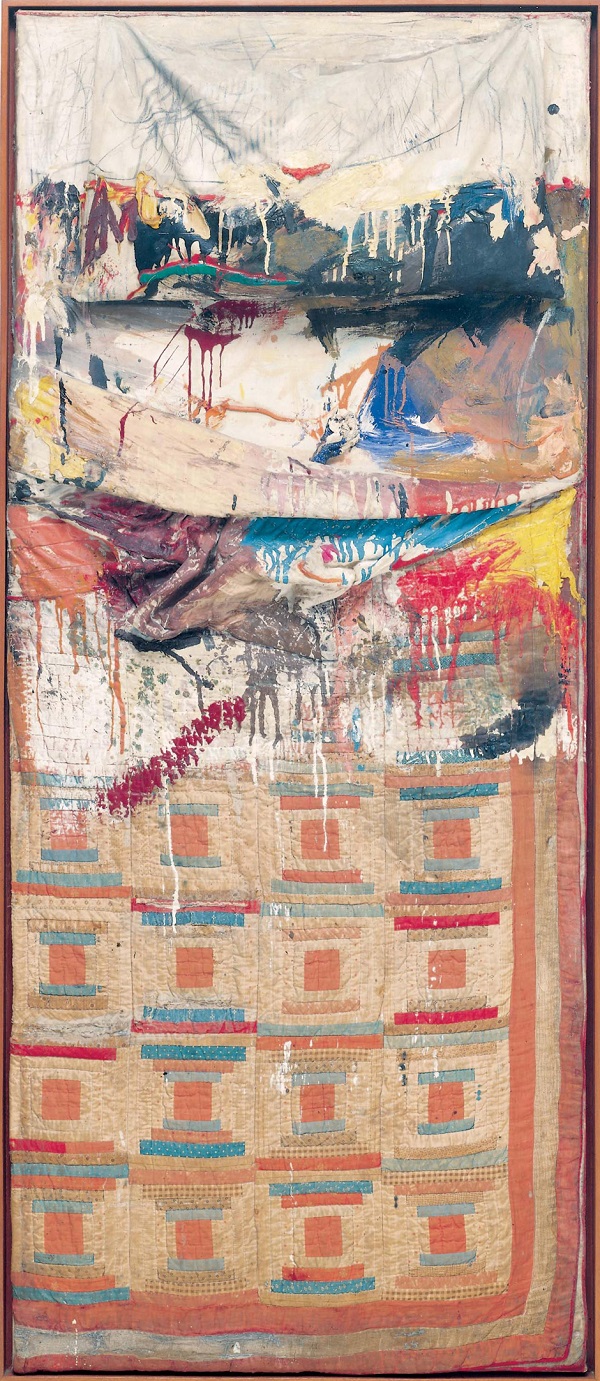

The Good American, a Texan no less, has landed at Tate Modern in style. This posthumous retrospective of the great Robert Rauschenberg includes a paint-bespattered, fully made-up bed hung vertically on the wall, and called – you guessed – Bed,1955 (pictured below right). A huge White Painting, 1951 – latex housepaint on seven panels, glossy and smooth – is joined by a huge, swirling, all-black painting, Untitled, c.1951, and an installation of various substances resembling bubbling mud, called Mud Muse, 1968-71. One gallery contains so-called Jammers, 1975-76, swathes of material leaning against the wall, inspired by the artist’s visit to Ahmedabad, India’s textile capital.

Silkscreened paintings blend imagery filched from the media, while another of his own idiosyncratic techniques – lighter fluid transferring media imagery to paper – features in a compelling series of emotive, whispery, ghost-like illustrations to Dante’s Inferno.

Rauschenberg (1925-2008) epitomises everything America once seemed to stand for: optimistic, energetic, original, collaborative, idiosyncratic, hilarious, serious, profound. In these bleak, unexpected and confusing times this amazing 20th century polymath appears courageous, positive and life-affirming, even as he acknowledged horrors from Vietnam to race riots. Tate's sampling is enthralling, demonstrating that Rauschenberg’s innovations and inventions changed not only visual language but also how artists work.

Rauschenberg (1925-2008) epitomises everything America once seemed to stand for: optimistic, energetic, original, collaborative, idiosyncratic, hilarious, serious, profound. In these bleak, unexpected and confusing times this amazing 20th century polymath appears courageous, positive and life-affirming, even as he acknowledged horrors from Vietnam to race riots. Tate's sampling is enthralling, demonstrating that Rauschenberg’s innovations and inventions changed not only visual language but also how artists work.

Monogram, 1955-59 (pictured below left), a stuffed, glassy-eyed Angora goat wearing a tyre round its torso, is a perfect demonstration of things acquired from inspired shopping, scavenging, street detritus, ephemera, all reconstructed and bound together with paint. The appearance of these mundane materials cobbled together with fierce and wayward intelligence is robust, but the work is also frustratingly delicate, let out from its home in the Moderna Museet in Stockholm for this occasion, and worth a visit in itself.

Art, said Rauschenberg, is more like the real world if it’s made out of the real world. An early example: John Cage drove his Model T Ford over a path made of sheets of typewriter paper covered with black house paint, to make just what the title of the work tells us, Automobile Tire Print, 1953. And perhaps he articulated the universal artist’s credo when he said that painting was the best way he had found to get along with himself. His aphorisms are alluring as they so perfectly express how he worked, with energy, terror, apprehension and excitement.

Rauschenberg was a handsome young man from Port Arthur, Texas (the home town, too, of Janice Joplin) who after army service got himself to art school, to Paris, then the progressive Black Mountain College, then New York and finally his compound on Captiva Island, Florida. He was a world traveller too, and for nearly a decade masterminded ROCI, Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange, starting in 1984. (Ironically or not, ROCI is also an acronym for "Return on Capital Invested".) Travelling the world he made a series of art works suggesting that art transcended spoken language: like benign pyramid selling, he left an art work in each major city he visited.

He was a photographer, a painter, a print maker, an illustrator, a choreographer, a set designer, creator of performance art before the term was used, not to mention installations, and other mixed media works he called "Combines", where found objects were transmogrified into huge sculptures and paintings. He was not only a highly individual artist but a collaborator too, working with the composer John Cage, and the choreographers Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown. One of his greatest gifts was knowing when he should move on. He left painting and silkscreening behind, but he returned to photography in his last decade, working with digital technologies and assistants when his right hand was affected by his two strokes.

He was a photographer, a painter, a print maker, an illustrator, a choreographer, a set designer, creator of performance art before the term was used, not to mention installations, and other mixed media works he called "Combines", where found objects were transmogrified into huge sculptures and paintings. He was not only a highly individual artist but a collaborator too, working with the composer John Cage, and the choreographers Merce Cunningham and Trisha Brown. One of his greatest gifts was knowing when he should move on. He left painting and silkscreening behind, but he returned to photography in his last decade, working with digital technologies and assistants when his right hand was affected by his two strokes.

Rauschenberg began with the possibilities of the material, and he considered that painting related to both art and life: “Neither can be made. I try to act in the gap between the two.” He was self-deprecating and declared that he had not been cursed with talent, as talent could be a great inhibitor. His work looks so easy and spontaneous, but it was painstaking: as he said “one needs a certain amount of trouble”.

Throughout the galleries there are videos of the many performances and dance projects with which Rauschenberg was involved, a reminder that he was always moving, restlessly, from project to project, subject to subject, riffing on the popular and the esoteric, the populist and the avant-garde. Above all, it is perhaps the ceaseless mix of imagery that overwhelms, especially pertinent in our information-saturated age. Things of acute significance are surrounded by day-glo colours and images from mass media, deployed for decorative as well as symbolic purposes. He was always looking out of the studio window at the world.

- Robert Rauschenberg at Tate Modern until April 2, 2017

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment