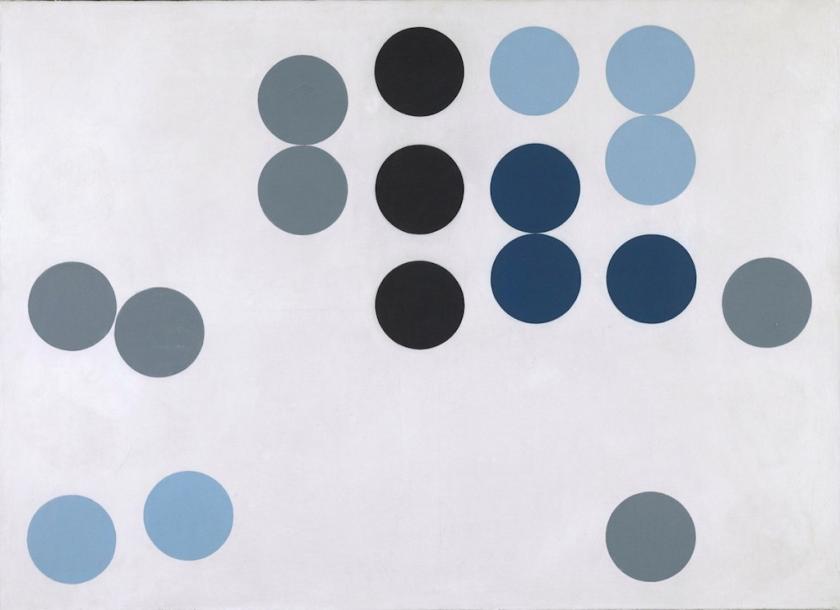

Sophie Taeuber-Arp gave her work titles like Movement of Lines, yet there’s nothing dull about her drawings and paintings. In her hands, the simplest compositions sizzle with tension and dance with implied motion. Animated Circles 1934 (main picture), consists of blue, grey and black circles on a white ground. The off-kilter design makes them appear to shuffle, nudge, float or bounce; you feel light-hearted and light-headed just looking at them.

Even in wartime she could make her work sing. In Geometric and Undulating Lines 1941 spaghetti-like strings rise flame-like over sharp triangles; the whole image seems to be on fire. It’s one of a series of drawings she did on the hoof while she and her husband, Jean Arp were keeping one step ahead of the German forces invading France, where they lived. The image could be a reflection of the flames enveloping Europe, but it’s also a defiant assertion of creativity.

Taeuber-Arp didn’t start making paintings until her late thirties; before that, she was busy doing other things. Born in Switzerland in 1889, she studied fine and applied arts in Munich and expressive dance at Rudolf Laban’s school in Zurich. With the outbreak of war in 1914, Zurich became a hot bed of radical art. Kurt Schwitters, Hugo Ball and Tristan Zara were among those who took refuge there and created Dada, a movement whose nonsense title was meant to offend the warmongers.

Taeuber-Arp didn’t start making paintings until her late thirties; before that, she was busy doing other things. Born in Switzerland in 1889, she studied fine and applied arts in Munich and expressive dance at Rudolf Laban’s school in Zurich. With the outbreak of war in 1914, Zurich became a hot bed of radical art. Kurt Schwitters, Hugo Ball and Tristan Zara were among those who took refuge there and created Dada, a movement whose nonsense title was meant to offend the warmongers.

Taeuber-Arp performed in absurdist Dada cabarets at the Cafe Voltaire. Wearing a mask and cardboard costume, she accompanied Hugo Ball’s abstract sound poems with a dance he described as “full of flashes and edges, full of dazzling light and penetrating intensity”. Sadly the only record is a photograph, but you can get some Idea of her moves by watching the video, playing at the exit to the show, of her glorious puppets in action.

They were commissioned in 1918 for King Stag, an 18th century play adapted to become an ironic take on psychoanalysis. Taeuber-Arp was adept at hand-turning wood, and the marionettes consist of wooden cylinders and cones linked by numerous joints that allow them to move with jerky fluidity (pictured below: installation shot by Seraphina Neville).

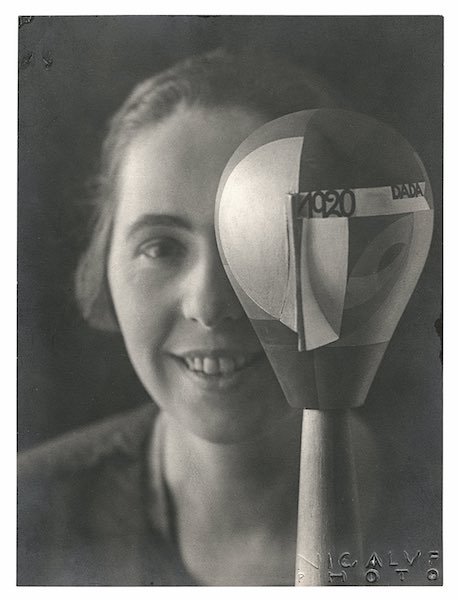

She also made wooden sculptures – egg-shaped heads painted with schematic features (pictured above right: the artist with a Dada head,1920) and abstract forms that double as cups or bowls. Distinctions between fine and applied art did not interest her. She was already gaining recognition as a textile designer and taught Applied Arts at the Trade School in Zurich. Her designs for embroideries, tapestries, rugs and cushion covers are exquisite little abstracts that any modernist painting would be proud of, while her beaded bags and necklaces are to die for. Everything she made has clarity, wit and grace; she had a magical touch.

Her first large scale commission came In 1926. It was to redesign a wing of the Aubette building, an entertainment complex in Strasburg. She decorated the walls and floors of a tea room and two bars with a syncopated pattern of vibrant geometric shapes, creating spaces akin to 3D paintings. Further commissions followed including a series of richly coloured, stained glass windows for the house of collector André Horn.

Her first large scale commission came In 1926. It was to redesign a wing of the Aubette building, an entertainment complex in Strasburg. She decorated the walls and floors of a tea room and two bars with a syncopated pattern of vibrant geometric shapes, creating spaces akin to 3D paintings. Further commissions followed including a series of richly coloured, stained glass windows for the house of collector André Horn.

As a result, she was able to buy a plot of land outside Paris and set about designing a house and studios for herself and her husband, complete with modular furniture. It soon became a meeting place for artists and designers including Sonia Delaunay, a kindred spirit whose skills similarly embraced both art and design. The surrealist Max Ernst visited along with writers James Joyce and Tristan Tzara.

Contact with the Paris art scene encouraged Taeuber-Arp to start painting and she was soon exhibiting alongside International modernists like Mondrian, Kandinsky and Le Corbusier. Her work is totally abstract yet somehow suggestive of human activity. In Six Spaces with Four Small Crosses,1932 (pictured below) she uses tilting planes to transform flat squares into ambiguous spaces reminiscent of architectural structures or a playground. Equilibrium,1934 brings to mind a juggler keeping several balls in the air. its playfulness and lightness of touch is typical of everything she undertook; It would make a fitting emblem for this amazing polymath.

Aged only 53 and at the height of her powers, she was tragically killed by carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty stove. You’d have thought her international reputation as an architect, designer and artist would have secured her a place in the history books but, as is so often the case with women artists, she was quickly forgotten by male curators, critics and historians and excluded from the record.

Aged only 53 and at the height of her powers, she was tragically killed by carbon monoxide poisoning from a faulty stove. You’d have thought her international reputation as an architect, designer and artist would have secured her a place in the history books but, as is so often the case with women artists, she was quickly forgotten by male curators, critics and historians and excluded from the record.

This show is, then, a revelation as well as a delight. It shouldn’t be; Sophie Taeuber-Arp should be as well known as other pioneers of modernism, but only now is she being given the recognition she deserves for her incredible achievements. More and more women are being rescued from oblivion by the efforts of female art historians, but I wonder how many more are mouldering in the dusty footnotes of art history still waiting for their contributions to be acknowledged.

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp is at Tate Modern until 17 October

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment