Tove Jansson (1914-2001), Dulwich Picture Gallery review – more than Moominvalley | reviews, news & interviews

Tove Jansson (1914-2001), Dulwich Picture Gallery review – more than Moominvalley

Tove Jansson (1914-2001), Dulwich Picture Gallery review – more than Moominvalley

Timely exhibition celebrates Finnish illustrator’s painterly ambition

Born into an artistic Swedish-speaking household in Helsinki, Tove Jansson’s first, and most enduring, ambition was to be a painter. Although best known as the illustrator behind the creatures of Moominvalley, those plump white hippopotamus-like folk with an existential longing for adventure, Jansson came to regard her widely successful creations as a distraction from what she considered to be her “real work”.

Jansson’s illustrations may have been exhibited in Britain before, but Dulwich Picture Gallery is the first to make explicit those connections between the artist’s graphic work and her paintings. The show opens with a room of early self-portraits, still-lifes and landscapes – the nuts and bolts of a fine-art education (Jansson studied in Stockholm and Paris, as well as at home in Finland) – and is dominated by Mysterious Landscape, c. 1930 (main picture). The painting, which shows an inky-black mountain streaked with rivers of alabaster-white alive with a supernatural glow, reveals an appetite for the fantastical that would come to fruition in the artist’s illustration work.

Jansson’s first solo show, held in 1943, was well-received by critics but many of her artistic peers eyed her evident commitment to symbolism with suspicion as art-world trends developed in the direction of abstraction. The exhibition’s second room shows an artist struggling to get to grips with the fashion for pictorial flatness, and some unconvincing abstract landscapes, with titles like Abstract Sea, 1963, demonstrate Jansson’s unwillingness to dispense with narrative altogether. Far more successful is Fennels, a wonderful still life from 1975, its affable white bulbs beautifully illuminated against the deep aubergine of the gallery wall.

Jansson’s first solo show, held in 1943, was well-received by critics but many of her artistic peers eyed her evident commitment to symbolism with suspicion as art-world trends developed in the direction of abstraction. The exhibition’s second room shows an artist struggling to get to grips with the fashion for pictorial flatness, and some unconvincing abstract landscapes, with titles like Abstract Sea, 1963, demonstrate Jansson’s unwillingness to dispense with narrative altogether. Far more successful is Fennels, a wonderful still life from 1975, its affable white bulbs beautifully illuminated against the deep aubergine of the gallery wall.

For all the exhibition’s efforts to rebalance Jansson’s reputation as a fine artist, however, there’s no doubting it is her illustrations that leave the greatest impression. The Moomins have run away with half the exhibition space, the majority of the drawings and prints are on loan from the recently opened Moomin Museum in Tampere, Finland, yet Jansson’s virtuoso talent as an illustrator extends far beyond Snufkin, Fillyjonk, and Little My. Her languid ink drawings for a Swedish edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1966, contain real menace, so that the scene of Alice’s descent down the rabbit hole becomes a watery underworld where bats glide overhead.

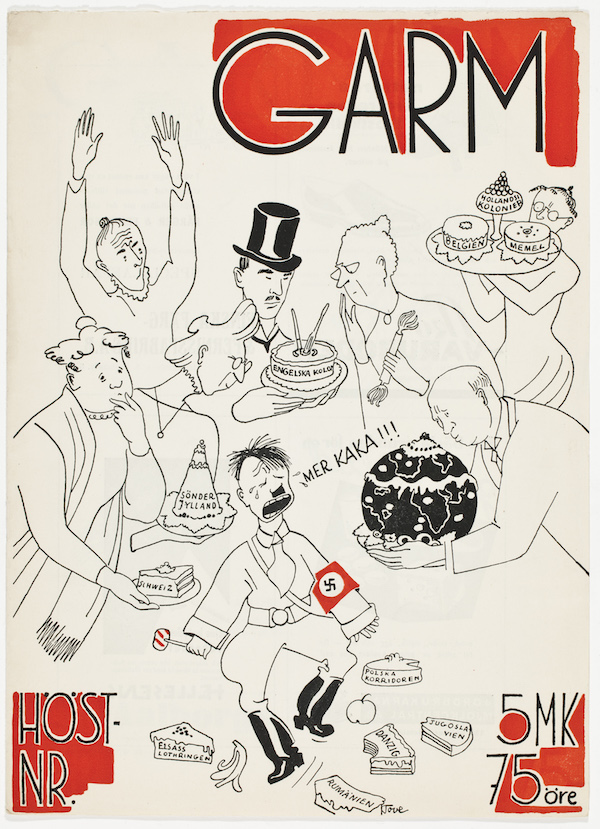

The make-believe world of the imagination is only half the story, however. Real-life events had a significant impact on the artist who was 25 and already a committed pacifist and champion of a universal humanism, as unfashionable in the 1930s as it is today, when the Second World War broke out. Jansson began contributing to Garm, a satirical Swedish language magazine, in 1929 and a collection of her cover designs is displayed in a case dedicated to the artist’s satirical work. A 1938 cover (pictured above, private collection) sees Hitler caught mid-tantrum, a lollipop held tightly in his fist, yelling “Mer Kaka!!!” (“More cake!!!”) as a swollen pudding the shape of a globe is handed to him on a plate. Slabs of half-eaten pie iced with the names of countries, along with a banana skin, litter the space around him.

The same wit and wisdom is on display in the last room of the exhibition, which offers a final treat: recently unearthed cartoon strips from the period, 1954 to 1959, when Jansson was under contract with London’s The Evening News. While most of the original art work from the Moomin comic strips has been lost, some early preparatory work survives. One such sketch charts Snorkmaiden’s struggle to get to grips with lipstick, a new discovery for a Snork with no obvious mouth. Should the waxy pigment be drawn on to the tip of one’s snout, directly below the eyes, or maybe across the side of a cheek? “Perhaps I am more beautiful without any,” she concludes at last.

The same wit and wisdom is on display in the last room of the exhibition, which offers a final treat: recently unearthed cartoon strips from the period, 1954 to 1959, when Jansson was under contract with London’s The Evening News. While most of the original art work from the Moomin comic strips has been lost, some early preparatory work survives. One such sketch charts Snorkmaiden’s struggle to get to grips with lipstick, a new discovery for a Snork with no obvious mouth. Should the waxy pigment be drawn on to the tip of one’s snout, directly below the eyes, or maybe across the side of a cheek? “Perhaps I am more beautiful without any,” she concludes at last.

Jansson’s fluency with pen and ink astonishes time and again yet I also came away with a new appreciation of her obvious talent as a colourist. A gouache sketch for The Dangerous Journey, 1977, one of five Moomin picture books, in which a girl suffering from summer ennui is transported, with the help of some magic reading glasses, to a world where birds fly upside down in salmon-pink skies, has stayed with me. The sketch shows an enormous black cat with eyes like limes hissing at the story’s heroine. The animal is so monstrous even the flowers in the ground are trying to tear themselves away but the girl remains as rigid as a stone. Her implacable expression is instantly recognisable from the imperious self-portraits found in the first room, and in particular Lynx Boa (Self-Portrait), 1942 (pictured above © Estate of Tove Jansson), which sees a steely-eyed Jansson, a dead lynx draped across her shoulders, hold herself erect against a background of, in the artist’s words, “fireworks made of flowers”. Even if it is for her illustrations that Jansson will most likely be remembered, this charming exhibition succeeds in drawing out the links between the magical world of the Moomins and the realism of the work she loved best.

- Tove Jansson (1914 - 2001) at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 28 January 2018

- More visual art reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment