The great Russian novelists of the 19th century wrote what Henry James called "large, loose, baggy monsters" out of belief that "truth" was more important than artistic form. The 20th-century Russian-Ukrainian writer A. Anatoli, who renounced his Soviet identity (and surname Kuznetsov) after defecting to England in 1969, was unquestionably an artist.

Yet he chose to subtitle Babi Yar, his classic non-fiction account of Ukraine's holocaust, "a document in the form of a novel". The book, first published in a heavily censored xxx in 1966, poses the question: why and how did the unprecedented horror of the German occupation of Ukraine occur? Unprecedented it may have been, but no longer unfamiliar or historically remote unfortunately, given what we now know about Russia's occupation of Ukraine since 24th February 2022.

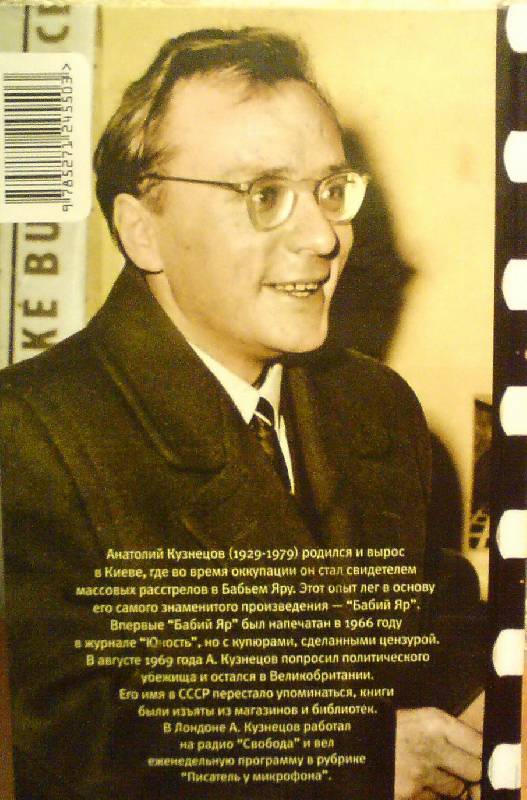

In September 1941, after seizing Kyiv, the Nazis killed 34,000 of the city's Jews in a single day at a ravine in the northern suburb of Babyn Yar (known as Babi Yar in Russian). The 12-year-old Anatoli witnessed the massacre. "This book contains nothing but the truth," he writes in the introduction. "IT ALL HAPPENED. Nothing has been invented and nothing exaggerated. It all happened to real, live people, and there is not the slightest element of literary fantasy in this book." There is, however, quite a lot of literary restitution, because the original Soviet edition cut those sections and even sentences that cast Stalinism in a less than favourable light. Escaping to London with the microfilm of his complete manuscript hidden in the lining of his jacket, Anatoli renounced his former self, declaring that published Soviet author to be "a cowardly and conformist writer", and began a 20-year task of publishing the book as he always intended it to be read. In this superb translation by the former Daily Telegraph journalist (and spy) David Floyd, the restored material is printed alongside the previously redacted text. (Pictured below, Anatoly Kuznetsov, cover image from a post-1991 Russian-language edition of Babi Yar)

In September 1941, after seizing Kyiv, the Nazis killed 34,000 of the city's Jews in a single day at a ravine in the northern suburb of Babyn Yar (known as Babi Yar in Russian). The 12-year-old Anatoli witnessed the massacre. "This book contains nothing but the truth," he writes in the introduction. "IT ALL HAPPENED. Nothing has been invented and nothing exaggerated. It all happened to real, live people, and there is not the slightest element of literary fantasy in this book." There is, however, quite a lot of literary restitution, because the original Soviet edition cut those sections and even sentences that cast Stalinism in a less than favourable light. Escaping to London with the microfilm of his complete manuscript hidden in the lining of his jacket, Anatoli renounced his former self, declaring that published Soviet author to be "a cowardly and conformist writer", and began a 20-year task of publishing the book as he always intended it to be read. In this superb translation by the former Daily Telegraph journalist (and spy) David Floyd, the restored material is printed alongside the previously redacted text. (Pictured below, Anatoly Kuznetsov, cover image from a post-1991 Russian-language edition of Babi Yar)

Anatoli was a 12-year-old child when he eyewitnesses the killing at Babi Yar, committed not only by German soldiers but also by Ukrainian collaborators who had been brutalised physically and morally by decades of Bolshevik rule. He revisits this back story as if to place the wartime genocide in historical context. For instance, a chapter entitled "Cannibals" that was excised altogether by the Kremlin's censors begins boldly, and in bold type, "The worst famine in Ukraine's long history occurred under Soviet rule in 1933. It is the first thing I can remember clearly in my life." A couple of pages on, it becomes obvious why the KGB got so busy with its blue pencil. Anatoli delivers an uncompromising judgment: "It was a man-made famine, brought about by Stalin. The peasants who resisted collectivisation had all their stores requisitioned. The population of many villages starves to death, to the very last person."

In these early vignettes, which have the descriptive power of Gorky's My Childhood, Anatoli's Russian father, a Communist policeman, abandons his Ukrainian wife, a schoolteacher, and as a result their only child grows up in Kyiv under the watchful eye of his maternal grandparents.

The wartime sections, based on Anatoli's first-hand observations, have the quality of reportage of the Ukrainian Jewish writer Vasily Grossman in Life and Fate, perhaps the greatest novel ever written about war – better than War and Peace, that is, because it's author, unlike Tolstoy, was actually an eyewitness to the conflict in question, in Grossman's case the battles for Kyiv and Stalingrad. Here, too, the degradation and horror are so vividly described that the reader sometimes has to put Anatoli's book aside to pause the trauma and despair: one woman, he writes, "did not see so much as feel the bodies falling from the ledge and the stream of bullets coming closer to her. Beneath her was a sea of bodies covered in blood. On the other side of the ravine she could just distinguish the machine-guns which had been set up there and a few German soldiers. They had lit a bonfire and it looked as though they were making coffee on it."

The wartime sections, based on Anatoli's first-hand observations, have the quality of reportage of the Ukrainian Jewish writer Vasily Grossman in Life and Fate, perhaps the greatest novel ever written about war – better than War and Peace, that is, because it's author, unlike Tolstoy, was actually an eyewitness to the conflict in question, in Grossman's case the battles for Kyiv and Stalingrad. Here, too, the degradation and horror are so vividly described that the reader sometimes has to put Anatoli's book aside to pause the trauma and despair: one woman, he writes, "did not see so much as feel the bodies falling from the ledge and the stream of bullets coming closer to her. Beneath her was a sea of bodies covered in blood. On the other side of the ravine she could just distinguish the machine-guns which had been set up there and a few German soldiers. They had lit a bonfire and it looked as though they were making coffee on it."

This is a book which was intended to be read as an historical document, or a warning from the past. Alas, that warning went unheeded, and was forgotten for half a century, and now we can't any longer read the book in the same way, because Ukraine is once again under an inhumane occupation. (Some of the scenes described by Anatoli evoke the senseless massacre of civilians that I witnessed a year ago in another Kyiv suburb called Bucha.)

Lenin supposedly remarked that "when we are ready to hang the capitalists, they will sell us the rope." But in Anatoli's frightful exposure of wickedness, the educated inhabitants of Kyiv are even more self-destructively in thrall to the dynamics of power. In Babi Yar, he explores the mentality (not confined to the ex-USSR) that leads people to follow prevailing opinion even when it contradicts moral principles. Working up his childhood notebooks and later journals, Kuznetsov wanted to offer the reader "truth" instead of politburo prose. He therefore included important documents in the text. Several chapters consist entirely of German propaganda notices or actual newspaper cuttings, including a football report on the so-called "Death Match" between Dynamo Kyiv and the German Army. The result is a work of formal idiosyncrasy unprecedented even in the Russian tradition of formally idiosyncratic works. It is a rediscovered masterpiece that must be read and never forgotten.

- Babi Yar: The Story of Ukraine's Holocaust by A. Anatoli, translated by David Floyd (Penguin: Vintage Classics, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment