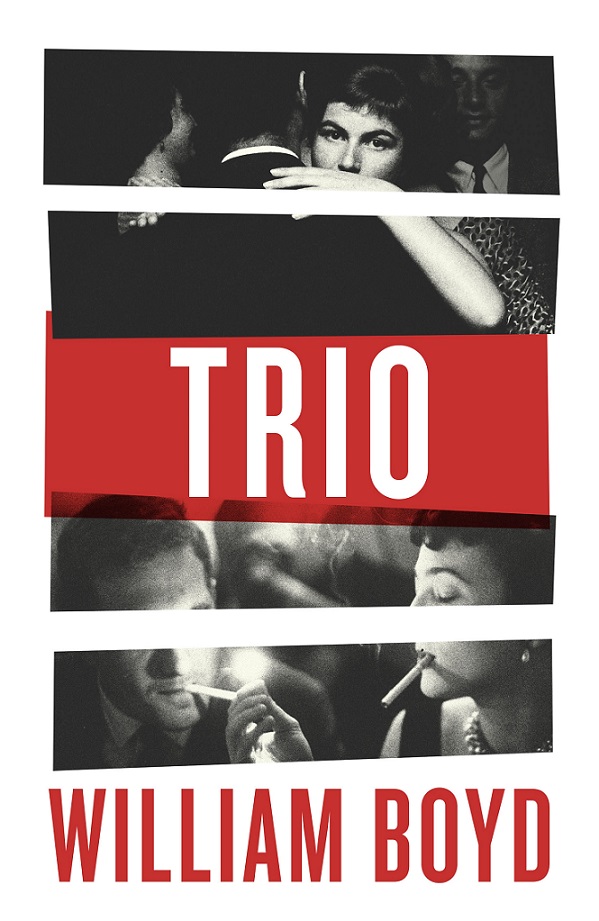

William Boyd’s fiction is populated by all manner of artists. Writers, painters, photographers, musicians and film-makers, drawn from real life or entirely fictional, are regular patrons of his stories. Boyd’s latest novel, Trio, is no different. Taking place on a film set in Brighton during the summer of 1968, Trio follows the lives of its three protagonists as they encounter the usual – and unusual – challenges of life in showbusiness. Artistic creation is the watchword both for the setting and its inhabitants.

Talbot, the film’s producer, Anny, its star, and Elfrida, a struggling writer, lead the way. Counting a philosopher, screenwriter and aspiring singer among its secondary cast, the novel depicts the whole gamut of artistic production. So much personality inevitably tells: private lives spill into the public sphere, well-kept secrets come back to haunt their holders, and the sense of foreboding steadily increases as Trio develops into a page-turning thriller.

Boyd treats the triangular structure of character narratives with a welcome degree of flexibility. Unafraid of playing with the order of chapters and changing their length (Talbot seems to enjoy more pages than Anny and Elfrida), he lets the story move organically along, avoiding any of the fragmentation that multiperspectivity can bring. The layering of detail, too, creates a distinctly three-dimensional world where real-life popular culture rubs shoulders with fictional creations, whether it be Elfrida’s previous novels that earned her the title of the “new Virginia Woolf”, the constant references to previous films that Talbot and Anny have worked on, or Talbot’s inability to keep out the tune of "MacArthur Park", released just that year. Boyd often goes further than most to encourage his reader’s suspension of disbelief (Nat Tate might be the best April Fools’ hoax ever), and even in the self-professed novel that is Trio, his characters can never quite be confined to the page.

If this play on fact and fiction resembles typical Boydian flair, the avowed focus of Trio is that other precarious opposition of private and public. Talbot, Anny and Elfrida each has a secret life that exerts a constant pressure on their public persona, and it is no surprise when all ultimately comes rushing out into the open. This tension makes for some wonderful scenes, such as the moment where Anny and co-star Troy, lovers inside and outside the film, exchange passionate words before kissing under the cameras. As Anny “closed her eyes and surrendered herself to the moment”, she enacts both a natural lover’s embrace and an entirely calculated one for an important scene in the film. Better yet is Elfrida’s opening to a new novel, which perfectly mirrors Boyd’s opening lines to Trio, an eloquent evocation of how a writer’s experiences permeate their fiction. “Art imitates life”, recognises Anny, but Boyd will keep us wondering whether the reverse is just as often true.

Though much of the novel treats this private/public theme with a quirky charm, there is an occasional tendency to overplay the detail. Our hospitable narrator is eager to spell things out for us, which makes for comfortable reading, at the cost of a degree of subtlety (phrases such as “Humphrey was their son” almost resemble footnotes). The most important mysteries, however, are kept nicely under wraps until the suitable "word-is-out" moment. Boyd’s game of hiding and revealing is framed by a narrator whose instinct to vouchsafe is restrained by the demands of novelistic suspense.

Though much of the novel treats this private/public theme with a quirky charm, there is an occasional tendency to overplay the detail. Our hospitable narrator is eager to spell things out for us, which makes for comfortable reading, at the cost of a degree of subtlety (phrases such as “Humphrey was their son” almost resemble footnotes). The most important mysteries, however, are kept nicely under wraps until the suitable "word-is-out" moment. Boyd’s game of hiding and revealing is framed by a narrator whose instinct to vouchsafe is restrained by the demands of novelistic suspense.

By its very nature, of course, a novel offers a chronicle of private life. Even for a writer such as Boyd, whose tracking of a historical period is as important as the lives of his characters (if not more so), Trio is keenly aware of the paradoxical relationship to secrecy a novel brings. The author’s masterstroke here is to complicate this aspect further, whether it be the actor Troy’s second identity as Nigel, or Talbot’s secret gallery within a secret apartment in London. Even our obliging narrator struggles to penetrate the many layers of its characters’ private lives. One point of regret, perhaps, is the slight underdevelopment of Elfrida’s characterisation. One step removed from Talbot and Anny, she never quite penetrates the central narrative of Trio, and is consequently left isolated, as if forming her own, separate story.

It is inevitable that the interweaving of private and public lives leads to more dramatic irruptions as the novel progresses. Indeed, there is a marked shift in the third part of the novel, imposingly named "ESCAPE", where the eccentricity of earlier sections makes way for a more unambiguous serving of thriller. Boyd confidently – and poignantly – picks apart the winding strands of his narrative in an extended dénouement whose style is on a par with any good crime fiction. Some moments of heavy symbolism remind us that this is a novel about the very process of artistic creation, but the ending more often recalls a previous thriller by this author, Ordinary Thunderstorms, where one misstep can snowball in terrifying fashion.

Trio, then, is an engrossing read, with flashes of Boyd’s classic flair as well as fresh moments of peculiar charm. Although the (genuine) excitement of the ending slightly detracts from its most creative aspects, the reader is left with a sense of the randomness, genius and arbitrariness of artistic production, encapsulated in the day-to-day life of the film set that provides the backdrop to each character’s private tribulations. Even if it does not quite approach Boyd’s best work, Trio is still an intelligent, entertaining and layered read.

- Trio by William Boyd (Viking, £18.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment