A truly terrifying sight this afternoon. The Wigmore Hall: full of children. A group of 50 10- to 13-year-olds were filing in to hear their first classical concert. On this one event a lifetime’s attitude to an entire art form would be based. It was make or break time. The concert would have to have been very carefully chosen. Hm. What had these wise teachers picked for these impressionable young rookies to ease their ears into the tough world of classical music? A lunchtime chamber recital of the works of Guillaume de Machaut, Harrison Birtwistle and Johannes Ockeghem. My instinct was to call social services.

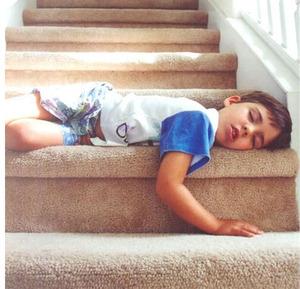

Now if you’re expecting me to report that actually the kids jumped up and down with joy when they heard the Birtwistle and demanded an encore, then you are going to be pretty disappointed. Of course what happened was what always happens when children who have lived their entire lives swimming in the amniotic fluid of pop are sat down in front of some classical music. See above.

They weren’t entirely to blame. Even by the standards of the Wigmore Hall this was esoteric programming. Pieces of Machaut, rearranged by Birtwistle for a small chamber group (string quartet, flute, clarinet, piano and percussion), interspersed with real bits of Birtwistle, bits of J S Bach rearranged by Birtwistle, a piece by contemporary composer Christian Mason (whose influences include Birtwistle) and a piece by Ockeghem, described in the programme as containing “one of the most convoluted and bewildering canons in all western music”, were played through without a pause. Good. So nothing too challenging, then.

Don't get me wrong. It was a great concert in many ways. Beautifully played and all that. The hocket compositional technique, which requires two performers to play a single melodic line in the form of a tennis rally, hitting notes to one and another, created a pretty fiendish level of difficulty and was executed with due diligence. A lot of this fiendishness was, I think, down to Birtwistle’s arranging, which required the string players to play or suggest each notes’ harmonics, the ethereal overtones that shadow each note and are only elicited when a string is touched, not pressed. But none of it - really none - was appropriate for an adult rookie, let alone a small, wide-eyed child.

The school party seemed as little convinced by Birtwistle’s chamber music as I have always been. His Double Hocket (2007) for piano trio was spritely and splashy, with a few nice turns, but little else to recommend it. The Lied (2006) coldly juxtaposes a trudging piano ground and a singing cello line, while his Verses (1965) for clarinet and piano from his youth have a call-of-the-wild presence to them.

It was difficult to criticise the arrangements of Bach's The Art of Fugue, seeing as the wispy legato feel to the Contrapunctus VII, the sense that bows had been glued to strings, was probably not the fault of the performers. There was something thrillingly rough-edged about first violinist Jacqueline Shave’s front-running in the Contrapunctus XII.

The Christian Mason piece, Noctilucence (2009), proved a rather empty affair in contrast to all this contrapuntal weaving. Deliberately so, by all accounts. The work is meant to mimic the highest clouds in our stratosphere. It did this well enough but then became fixated on some rather too pronounced and hoary musical ideas: a piano glissando and a boorish lyrical idea.

To finish we had some curiously festive Ockeghem, his Ut heremita solus, after which I heard a child scream, “That’s so cool!” Not the world’s youngest Ockeghem fan, sadly, it had simply started to snow and the faces of three rows of bored children suddenly lit up with excitement.

Add comment