The Way of Light – The Music of Nigel Hess (Orchid Classics)

The Way of Light – The Music of Nigel Hess (Orchid Classics)

You’ve probably heard Nigel Hess’s music without realising it. He’s scored multiple RSC productions and has provided incidental music for dozens of films and television programmes. Here we’ve a selection of what Hess calls his ‘stand-alone music’, in energetic, lively performances. Hess’s tonal language is fluent and readily accessible. There’s more than a hint of Malcolm Arnold in A Celebration Overture, composed for the 175th anniversary of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic. It’s anachronistic but fun; you can imagine it playing over a 1950s public information film. The March Barnes Wallis has a similarly retro feel and opens with a terrific flourish, though his trio theme can’t compete with Eric Coates’s, and I’m a little uncomfortable with any contemporary work which commemorates aerial bombardment.

Less contentious is a three-movement suite drawn from the ballet The Old Man of Lochnagar, based on the children’s book by HRH Prince Charles. Think Arnold’s Tam O’Shanter or Maxwell Davies’s Orkney Wedding and Sunrise, Hess effortlessly assimilating Scottish folk music. A winning Nocturne for left-hand piano is beautifully played by Nicholas McCarthy, and Piers Lane performs the Jesu Joy Variations, a tribute to the concerts organised at the National Gallery during World War II by the composer’s great-aunt, Dame Myra Hess. The Lakes of Cold Fen has fun with a Cambridgeshire folk song and there’s a selection of choral numbers. Most striking is the 2009 Benedictus, the bright-toned voices of the St Catherine’s College Girls Choir giving Hess’s incisive rhythms just enough lift. Performances, from a variety of sources, are consistently good, Richard Balcome’s versatile BBC Concert Orchestra worthy of special praise.

Martinů: Violin Concertos, Bartók: Sonata for Solo Violin Frank Peter Zimmermann (violin), Bamberger Symphoniker/Jakub Hrůša (BIS)

Martinů: Violin Concertos, Bartók: Sonata for Solo Violin Frank Peter Zimmermann (violin), Bamberger Symphoniker/Jakub Hrůša (BIS)

Martinů's Violin Concerto No. 1 was commissioned in 1932 by Samuel Dushkin, who also persuaded Stravinsky to write him a concerto. Stravinsky wasn't a string player and was happy to accept Dushkin's help and advice while composing. Martinů was an experienced violinist and his collaboration with Dushkin was fraught, with the composer under constant pressure to amend the solo writing. The piece was eventually shelved and believed lost, turning up in a university archive in the 1960s and eventually performed in 1973 by violinist Josef Suk, whose composer grandfather is mentioned below. The bustling neo-classical opening is typical of Martinů's early style, the solo violin writing extremely demanding. A lyrical slow movement offers some relief before a jazz-influenced finale. It's an enjoyable piece, brilliantly performed here by Frank Peter Zimmermann with luminous support from Jakub Hrůša's Bamberg players.

The glorious blazing chord that opens the Second Violin Concerto recalls Martinů's mature symphonies, the work composed in 1943 after he'd moved to the US. It's a more balanced piece, Zimmermann's cantabile playing in the first movement's long lines making a fabulous case for it as one of the great 20th century concertos. He and Hrůša relish the music's luminosity, notably in a radiant account of the central "Andante moderato", and the concerto's upbeat final bars are exhilarating. Zimmermann plays Bartók's late Sonata for Solo Violin as a coupling, another wartime commission from a composer in exile. Zimmermann accentuates the opening section's nods to Bach, and clarifies Bartók's thorny fugue. The third movement "Melodia" is rapt and intense, before a sparky finale. Wonderful stuff – all three works brilliantly performed and warmly recorded.

Josef Suk: Piano and Chamber Music Kiveli Dörken (piano), with Christian Tetzlaff, Florian Donderer, Timothy Ridout and Tanja Tetzlaff (Ars Produktion)

Josef Suk: Piano and Chamber Music Kiveli Dörken (piano), with Christian Tetzlaff, Florian Donderer, Timothy Ridout and Tanja Tetzlaff (Ars Produktion)

Josef Suk’s Asrael Symphony is almost a repertoire work, but he’s still an underrated figure in the UK. The Piano Quintet in G minor is an early work from 1893, dedicated to Brahms, a close friend of Suk’s teacher Dvořák. Suk revised the piece in 1915; that it still feels indebted to the two older composers isn’t to disparage it at all. This is such confident music: Suk opens with a bold flourish and never lets up. He’s especially good at transitions, as with the dotted first subject’s seguing into the lyrical second theme. And how well the material is shared between the five players, pianist Kiveli Dörken frequently stepping back and allowing solo strings to shine; the beginning of the slow movement is sublime in this performance. That she’s partnered with a quartet led by violinist Christian Tetzlaff is a bonus, but you’re struck by how carefully these players listen to one another; they sound as if they’ve worked together for years. The same movement’s ecstatic middle section glows, Suk then letting his hair down with an unbuttoned, folksy scherzo and a propulsive finale. A beautiful work, handsomely performed.

Suk’s Things Lived and Dreamt is the coupling, a cycle of 10 autobiographical piano pieces. He hides nothing, the pieces’ subtitles referring to a variety of moods, Suk fuming, feeling restless, carefree or “increasingly aggressive” at various points. There’s a moving reminiscence of his son recovering from a serious illness and a visit to the graves of his wife and parents in an overgrown churchyard, distant bells pealing. Dörken nails each one, distilling the essence of Suk’s character in front of our ears. An outstanding disc, superbly engineered. Don’t be put off by the sombre sleeve art; this release contains some joyous music making.

Matthew Taylor: Symphonies 4 and 5, Romanza for Strings BBC National Orchestra of Wales, English Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Woods (Nimbus)

Matthew Taylor: Symphonies 4 and 5, Romanza for Strings BBC National Orchestra of Wales, English Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Woods (Nimbus)

Matthew Taylor’s Symphony No. 4 was conceived as a tribute to his late friend John McCabe. The two men shared a love of Nielsen and Haydn, Taylor echoing the older composers’ quirks in this engrossing three-movement work. Though written in memoriam, this isn’t downbeat music, Matthews believing that “the best way to pay tribute is to adopt an approach that is essentially celebratory in spirit.” Taylor’s very Nielsen-esque opening, in swinging triple time, is immediately appealing, and there’s an extraordinary passage just a few minutes in, harps and tuned percussion impersonating a gamelan orchestra. The energy doesn’t abate and there’s an epic, thrilling slowdown at the movement’s close. A central “Adagio teneramente” offers contrast: dark, richly melodic and beautifully scored, while a fast finale brilliantly balances humour with gravitas, conductor Kenneth Woods describing it as “a mix of joy and nobility”. It’s really, really good, and coupled with Taylor’s Symphony No. 5, commissioned as part of Woods and his English Symphony Orchestra’s 21st Century Symphony project.

When first talking to Woods, Taylor described a single movement work; what emerged in 2018 was a large scale, four-movement symphony. It’s darker than its predecessor but audibly cut from the same cloth. Taylor’s structural savviness makes his music compelling; the ideas are so cleanly delineated and there’s no padding, the propulsive first movement “Allegro” abruptly stopping with a grunt in low brass. Two short, graceful middle movements pay tribute to late friends, and Taylor’s slow finale is dedicated to the memory of his mother. Brilliantly sustained and very moving, the final seconds are powerfully effective, Taylor’s soft string writing cut short by a sepulchral trombone chord. Two outstanding contemporary symphonies, then, given incisive, authoritative performances and very well engineered. Taylor’s Romanza for Strings, arranged from a string quartet movement, is an eloquent coupling.

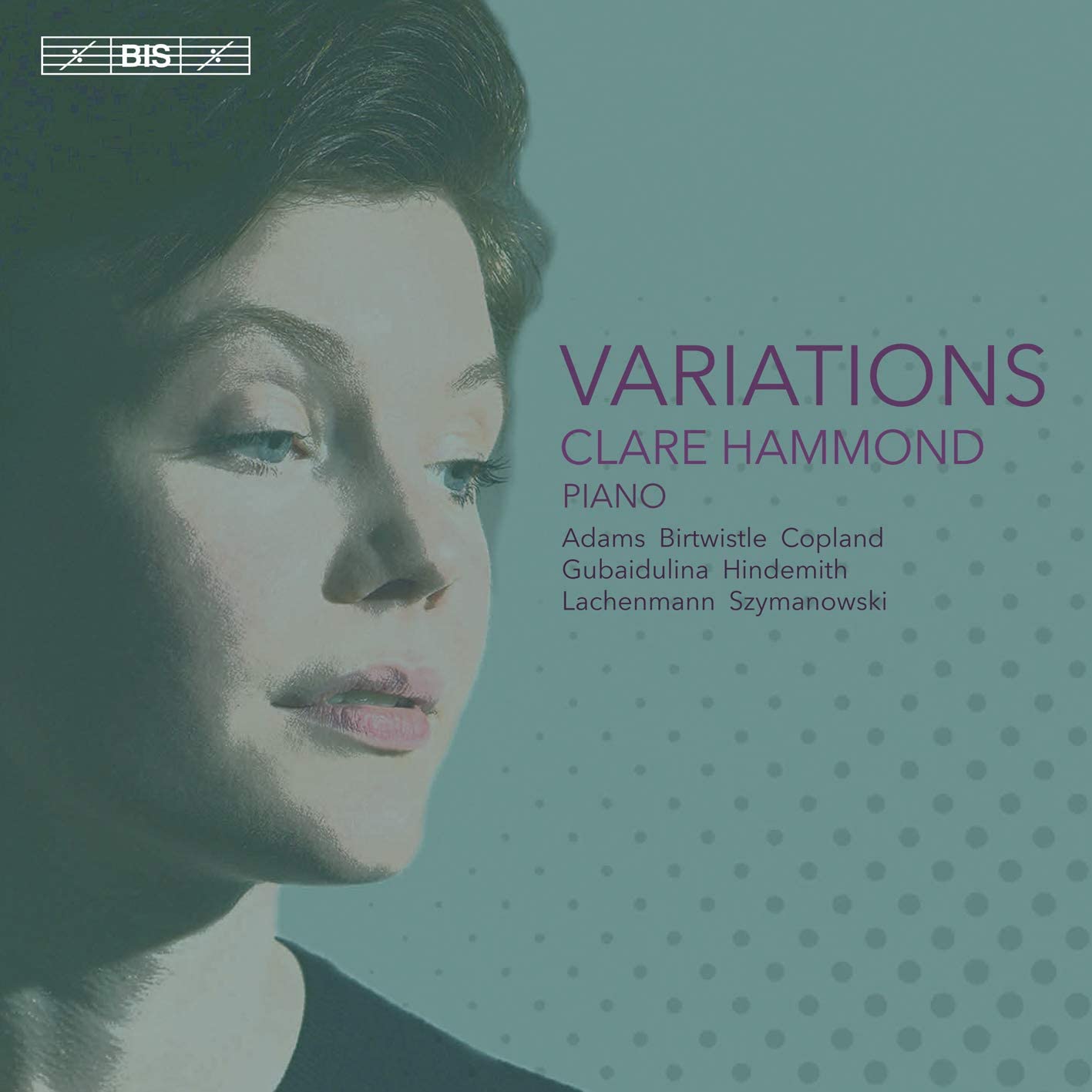

Clare Hammond: Variations (BIS)

Clare Hammond: Variations (BIS)

Pianist Clare Hammond has an excellent track record in demystifying offbeat repertoire, and this compilation plays to her strengths. None of this music is familiar, though Copland’s thorny, early Piano Variations is one of those works that many have heard of, even if they haven’t actually heard it. Start here: Hammond’s magisterial performance, in immaculate sound, is a wowzer. The sense of space, the music’s clean edges, are typical Copland, though the dissonant language may surprise, the four-note theme manipulated to thunderous effect. It’s preceded by John Adams’s emotionally cool but attractive I Still Play, designed to be accessible to competent amateur pianists. Hindemith’s Variations, extracted from an early piano sonata, display his contrapuntal gifts and close with an utterly characteristic tonal cadence.

Szymanowski’s Variations on a Polish Theme is the longest and earliest work included, 10 appealing variations on a folk song, a sharp contrast to Helmut Lachenmann’s Five Variations on a Theme of Schubert. Lachenmann quickly takes us far from Schubert’s D643 Écossaise, Hammond perfectly attuned to each variation’s character. Harrison Birtwistle’s Variations from the Golden Mountains doesn’t give up its secrets readily; the hefty Chaconne by Sofia Gubaidulina makes more of an impact, especially a passage where thunderous, deep chords ring out over high trills.

Alexandra Sostmann: Bach, Byrd, Gibbons & Contemporary Music (Tyxart)

Alexandra Sostmann: Bach, Byrd, Gibbons & Contemporary Music (Tyxart)

Alexandra Sostmann shares with Hammond the ability to render the most arcane repertoire readily accessible. Her disc spans four centuries, her intention being to highlight “the connections between different epochs and their polyphonic structures”. Listen straight through and you move from a clear-sighted extract from Bach’s Musical Offering, each strand perfectly balanced, to Knussen’s “Prayer Bell Sketch”, a tribute to his friend Takemitsu, who’d admitted that he found it difficult to translate bell sounds to the piano. Knussen lets us hear the overtones and overlapping chords, his bells booming slowly then tinkling in the central section. Sostmann balances each chord to perfection. Two short numbers by Byrd are paired with the “Piece after Byrd” by Sostmann’s friend Markus Horn. Though jazzy and improvisatory in feel, Horn preserves Byrd’s melancholy. Several short pieces by John Tavener were new to me. “In memory of my two cats” is an exquisite, melancholy miniature, as is “Zodiac”, each soft chord unexpected but inevitable.

John Adams’s early “China Gates” is an ingenious musical palindrome inspired by Californian rainfall. Not that you’d notice without inspecting the score, Adams’ rippling arpeggios sounding as if Sostmann is improvising them on the spot. And a Pavan and Galliard by Orlando Gibbons feel thoroughly at home on a Steinway. An absorbing anthology, the final Bach item sounding all the more fresh after what’s gone before.

Add comment