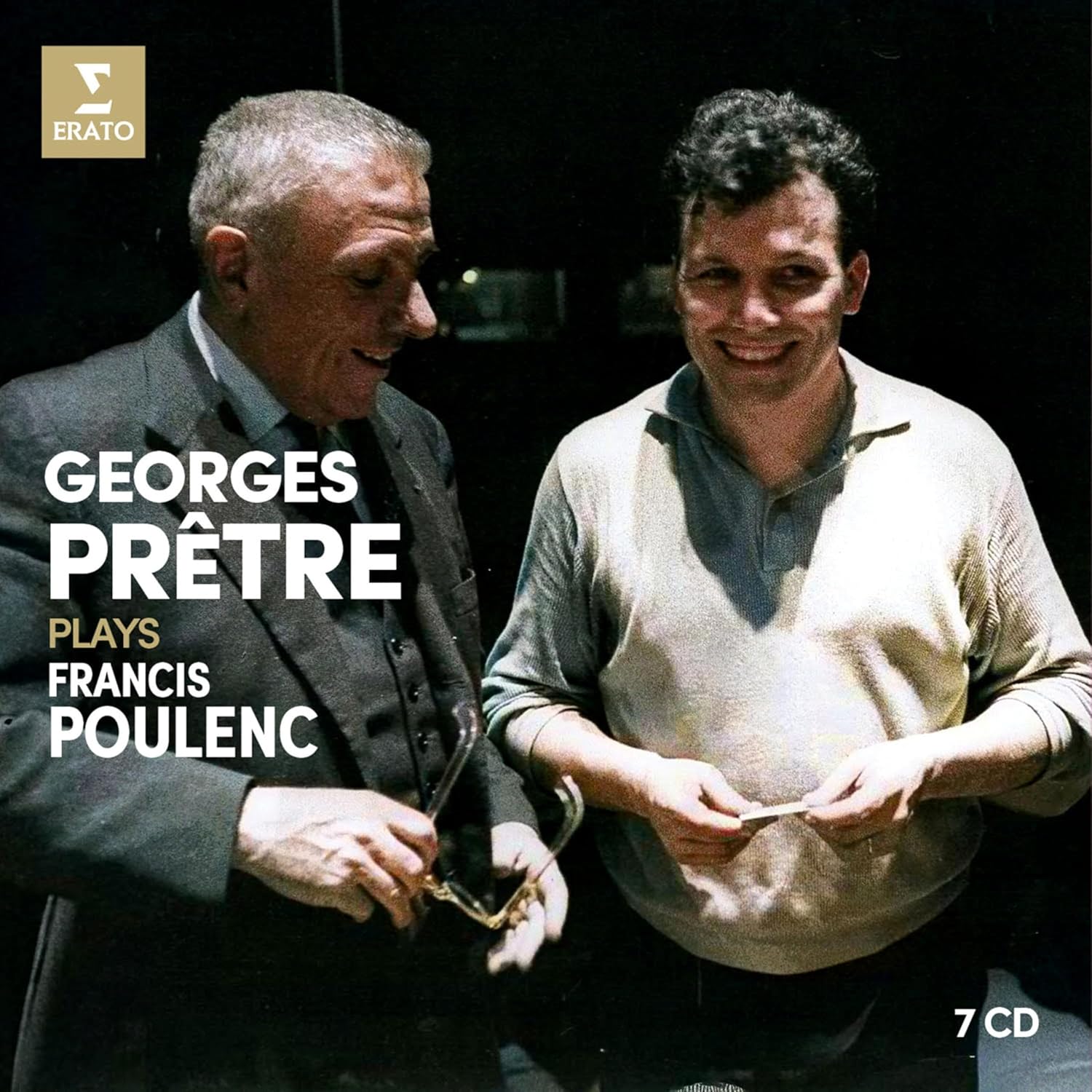

Georges Prêtre plays Francis Poulenc (Erato)

Georges Prêtre plays Francis Poulenc (Erato)

Georges Prêtre and Francis Poulenc’s working relationship began in 1959 when Prêtre conducted the first staging of La Voix humaine with soprano Denise Duval. Already an experienced opera conductor, Prêtre’s performance moved Poulenc to tears, and he was soon entrusted with the French premiere of the Gloria. It’s a little frustrating that Prêtre’s first recording of this work, taped with Rosanna Carteri as soloist, isn’t included in this 7-disc box set. Nor is his pioneering account of the Stabat Mater. Instead, we get the 1980s remakes with Barbara Hendricks. These are very good, though I miss the rawer sound of the Orchestre National de la RTF. Also missing is an early Parisian version of the suite from Les Biches. These are minor gripes, as there’s a sizeable pile of great stuff here. Poulenc indicated shortly before his death in 1963 that he wanted Prêtre to record his orchestral music, so the discs have real historical value.

I was drawn to the rarities. Try CD 5, which opens with a perky 1980 Philharmonia account of the complete Les Biches, with vivid choral contributions from the Ambrosian Singers. Followed by Prêtre’s still-definitive first recording of Poulenc’s Sept répons des ténèbres, a 1961 New York Philharmonic commission which the composer didn’t live to hear performed. This late masterpiece, angrier and more dissonant than the Gloria, contains some sublime music. Try the very opening, Prêtre nailing the shifts between serenity and violence. Using an all-male chorus gives the work a dark caste, and the treble soloist is magnificent. The work’s quiet final seconds are extraordinary: listen and weep. The very Stravinskian secular cantata Sécheresses is another novelty, and that we can hear it at all is a bonus; the 1938 premiere wasn’t a success and Poulenc came close to destroying the manuscript. You’ll have to track down the texts (translations of poetry by Edward James) online but it’s worth the effort.

Prêtre’s famous 1961 performance of the Organ Concerto with Maurice Duruflé as soloist is here. There are also wonderful readings of the Concert champêtre and Concerto for Two Pianos made with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo. Jean-Patrice Brossard’s beefy harpsichord sounds like no other on record, and there’s some spiky playing from pianists Gabriel Tacchino and Bernard Ringeissen in the D minor work. Listen out for the castanets, more audible than in any other performance I know. Tacchino also plays the Piano Concerto and Aubade, both dispatched with a near-perfect blend of tartness and lyricism. 1960s recordings of the lovely Sinfonietta and the suite from the ballet Les Animaux modèles hold up well, and there’s an intriguing selection of smaller pieces. The Suite francaise comes in a 1968 performance from the recently formed Orchestra de Paris, and baritone Jean-Christophe Benoit is excellent in the Chansons villageoises and Le Bal masque. Plus, Peter Ustinov narrates both French and English versions of L’Histoire de Babar in the idiomatic Jean Françaix orchestration. New to me was the brief but poignant ‘monologue pour chant et orchestra’ La Dame de Monte-Carlo with a text by Jean Cocteau, very well sung by soprano Mady Mespié. Prêtre’s final Poulenc recording was an uneven 1990 remake of La Voix humaine with soprano Julia Migenes. You won’t find that here – sensibly, Erato have opted to include instead the 1959 Duval original, which is fabulous. François Laurent’s sleeve note provides a useful chronology of Prêtre’s Poulenc recordings, and the original sleeve designs have been retained. This little package is a steal – snap up a copy while you can.

Elgar and Walton: Cello Concertos Gautier Capuçon, London Symphony Orchestra/Antonio Pappano (Erato)

Elgar and Walton: Cello Concertos Gautier Capuçon, London Symphony Orchestra/Antonio Pappano (Erato)

New recordings of the greatest of English cello concertos are always welcome, and noting that Gautier Capuçon and Antonio Pappano get through Walton’s first movement in 8’24” tells you that they understand how this music has to move. Walton’s marking is moderato, not andante; take things too leisurely and things start to fall apart. The concerto’s opening, a ticking clock accompanied by barely audible string tremolandi, is hypnotic here, and listen to how Capuçon digs in to his first entry. It’s gorgeous, in his words “a melody that is erotic as it is beautiful,” and resistance is futile. Listening to this music is like sipping a Campari, Pappano drawing exquisite colours from the LSO as the movement dies away. The central scherzo also moves, with a blink-and-you’ll-miss it payoff from Capuçon, compelling in the finale’s long unaccompanied passages. Pappano gives the central toccata plenty of bite, and the concerto’s long slow fade is incredibly moving. Glorious, in other words: my go-to recording has long been Paul Tortelier’s 1973 LP, but Capuçon hits the spot with similar élan.

Elgar’s similarly introspective Cello Concerto is an appropriate coupling. Hard to believe that this was once a seldom-performed piece, a quote from Pappano in the booklet pointing out that the 1965 Jacqueline du Pré recording helped establish it as a repertoire work. This new account benefits from some wonderfully rich orchestral playing, and the big tutti at 2’40” is seismic here. In Pappano’s words, “English music really has a lot to say if it’s done with full-on intensity and drama”, and his big-hearted approach beautifully compliments Capuçon’s intense, intelligent playing. Elgar’s “Adagio” really sings, and the big slow tune near the concerto’s close is heart-stopping. Seriously good, then, and beautifully recorded at LSO St Luke’s.

Imogen Holst: Discovering Imogen BBC Concert Orchestra, BBC Singers/Alice Farnham (NMC)

Imogen Holst: Discovering Imogen BBC Concert Orchestra, BBC Singers/Alice Farnham (NMC)

There is an excellent aptness to this album coming out on NMC. Imogen Holst set up the Holst Foundation shortly before her death in 1984, and it was an early supporter of the label. Although NMC’s remit is music by living composers, it is surely fitting that they devote this disc to a composer largely overlooked during her life, and since her death. This is partly because of her own self-effacement regarding her compositional work – a result of her natural modesty as well as awareness of her own situation of being in the shadow of her father (whose work she tirelessly promoted after his death). Her output of 200 pieces is also impressive in the light of her other work, as teacher and, for more than a decade, as valued assistant to Benjamin Britten. So this album is not before its time, but no less welcome for that, featuring seven works of which, extraordinarily, only one has previously had a professional performance. The two choral works, sung by the BBC Singers, have never been performed before at all.

The first piece is a 13-minute orchestral overture called Persephone, dating from her student days at the Royal College of Music, given a colourful reading by the BBC Concert Orchestra. It sounds quite like Holst senior in places, with touches of Ravel too, but that is not to damn it with faint praise. It is very well-scored and nicely paced, mostly slow and dreamy and deserves performances – it would be suited to non-professional orchestras looking to widen their repertoire. It is sad that Holst never worked on that scale again, perhaps discouraged by Persephone’s reception. Variations on ‘Loth to depart’ (from 1962) was written for school-age players, and is typically well-designed for its purposes. Accessible technically but not without compositional interest, with some spiky dissonances and lively rhythms.

The choir-and-orchestra settings What Man is He? and Festival Anthem are dignified and weighty. The Festival Anthem (orchestrator unidentified in the booklet) is varied enough to sustain its 14-minute duration, and the BBC Singers treat it with appropriate solemnity – although it is never po-faced. Perhaps the most interesting piece on the disc is the Suite for String Orchestra, premiered at the Wigmore Hall in 1942. Here Holst’s harmonic language is a bit more developed and she is obviously spreading her wings in a rare opportunity to write for a professional string orchestra. The transition from the brooding “Intermezzo” into the “Jig” finale (a Holst family trait, apparently) is particularly effective. Conductor Alice Farnham and the BBCCO – and NMC too, of course – are to be commended for putting t. these pieces into the world. Hopefully the disc will act as a sampler that will ensure that they get played more now, 40 years after her death, that they have up till now. - Bernard Hughes

Adrian Sutton: Orchestral Works Fenella Humphreys (violin), BBC Philharmonic/Michael Seal (Chandos)

Adrian Sutton: Orchestral Works Fenella Humphreys (violin), BBC Philharmonic/Michael Seal (Chandos)

Adrian Sutton has found fame as a theatrical composer, best known music for National Theatre productions of War Horse and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night. The final work on this disc, Five Theatre Miniatures works as a brilliant calling card for Sutton’s musical fluency, each short movement expanded from a theatrical cue. “The Departure” began life in a stage adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express and it’s a blast, three and a half minutes of propulsive, snarling train music paying affectionate homage to Honegger’s Pacific 231. That it’s a musical palindrome adds to the fun, Sutton reversing his melodic and harmonic material halfway through. A tiny “Gigue” from Coram Boy pastiches Handel and the suite ends with a hair-raising tarantella composed for antiseptic epic Dr Semmelweiss, staged in 2022 with Mark Rylance as the lead. An extended suite from War Horse glows, Sutton’s exciting depiction of Joey’s first gallop rivalling Denis King’s iconic 1970s Black Beauty theme. English pastoralism yields to French impressionism once Joey crosses the Channel and the closing movement avoids easy sentimentality. 2016’s A Fist Full of Fives, to be played ‘with huge fire and rhythmic energy’ is a thrilling scherzo in quintuple time, Sutton making prominent use of the interval of a fifth and having five main themes. Michael Seal’s BBC Philharmonic give it ample oomph, the orchestral playing bold and fearless.

Sutton was given a terminal cancer diagnosis in September 2022, the composer resolving “to avoid egregious waste of both time and energy ruminating on things I can’t change” and to throw himself into composing music for the concert hall. The most substantial work on the disc is his 25 minute Violin Concerto (1923), which took inspiration from The Lark Ascending and Richard Bach’s 1970s bestseller Jonathan Livingstone Seagull. The solo line soars, Sutton shooting out ideas thick and fast. Fenella Humphreys is a fearless soloist, golden-toned in the lyrical central movement and athletic in the faster sections. Beautifully scored and well-proportioned, it’s a harder work to love than the shorter, punchier theatre pieces. 2022’s Short Story worked better for me, an eight-minute tone poem whose narrative isn’t disclosed, though a tense central climax is nicely resolved before a serene close.

Adrift: music by Kenneth Leighton, Mátyás Seiber et al Delphine Trio: Magdalenna Krstevska (clarinet), Jobine Siekman (cello), Roelof Temmingh (piano) (TRPTK)

Adrift: music by Kenneth Leighton, Mátyás Seiber et al Delphine Trio: Magdalenna Krstevska (clarinet), Jobine Siekman (cello), Roelof Temmingh (piano) (TRPTK)

This trio brings together musicians from three continents who love working together: a clarinettist from Melbourne with Macedonian/Bulgarian origins, a cellist from Groningen and a pianist from Stellenbosch. They got together in 2020 as postgrads at the Royal College of Music, were finalists at the ROSL competition in 2022 and have developed real momentum and common purpose as a team of equals. Adrift is billed as their debut album, although they have previously recorded a rather earnest EP of works by Robert Muczynski. Listening to that earlier recording, one cannot fail to notice a real uptick of enthusiasm about the whole of this new album, starting with the three not playing but singing “Shall We Gather by River”, the American hymn tune on which Kenneth Leighton based his highly melodic and finely crafted Fantasy from 1974. Everything here is played with a sense of commitment and belief. The highlight among the works is the last track.

Mátyás Seiber’s Introduction and Allegro from 1939 is a gem. The Delphine Trio found the manuscript in the Royal College of Music’s library, and thanks to the involvement of Julia Seiber Boyd of the Mátyás Seiber Trust, it has been published by Schotts. The piece quotes Ravel’s Bolero rather than the other Ravel work after which it is named. Starting gently, it gradually and inexorably gets swept up in a whirlwind of exuberance which the Delphine Trio capture delightfully and energetically together. Liner notes are thoughtful and clear, the recorded sound from the Muziekcentrum van de Omroep in Hilversum is excellent, and the clarinettist in your life might not know it yet, but she or he is going to want to play the Seiber. - Sebastian Scotney

The Delphine Trio are at St. Catharine's College Chapel in Cambridge on 22 November

Welcome Joy: A Celebration of Women’s Voices Corvus Consort/Freddie Crowley, with Louise Thomson (harp) (Chandos)

Welcome Joy: A Celebration of Women’s Voices Corvus Consort/Freddie Crowley, with Louise Thomson (harp) (Chandos)

You wait forever for recordings of Imogen Holst, then two pop up in the same week. I’ve just reviewed the NMC/BBC Concert Orchestra album of her orchestral music and next on my pile is a choral selection by Corvus Consort, placing her alongside other women composers as well as her father, Gustav. The music is all for upper voices (giving a double meaning to the album’s subtitle), mostly with harp, the multi-faceted Louise Thomson. Corvus are a young choral ensemble under the leadership of Freddie Crowley. They are an innovative and top-drawer ensemble, presenting their second album on Chandos, after Revoiced, their excellent 2022 collaboration with the Ferio Saxophone Quartet.

Imogen Holst kicks things off, with her Welcome Joy and Welcome Sorrow (1950), a setting of a six-poem sequence by Keats, written for the Aldeburgh Festival. The short movements are neatly individuated, both in their varied vocal textures and the range of harp writing. Britten described them as “little treasures”, and I can only agree. There are three bursts of Gustav Holst, and the best is probably the Two Eastern Pictures, combining his distinctly English sound with some unusual and winning harmonic twists. Best known are the Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda, in which the choir are spry in the first, elegantly long-breathed in the second and ghostly and distant in the third. The final item, Dirge and Hymneal, was new to me, dating from the time he was writing The Planets, referencing the chords of “Saturn”, then spinning off in a different direction. A nice find.

For the rest, there is an 11-song sequence An English Day-Book by Imogen Holst’s close contemporary Elizabeth Poston. She is famous for the carol "Jesus Christ the Apple-tree", which I cordially detest, so I was delighted to find some Poston that I like. Her medieval-inflected writing works is well judged, very subtle, and subtly sung. There are individual pieces by five living composers, Judith Weir, Hilary Campbell, Gemma McGregor, Olivia Sparkhall and Shruthi Rajasekar. The Weir, McGregor and Campbell pieces were all commissioned by Multitude of Voyces, a publishing charity that is doing great work promoting women composers. They all set words by Julian of Norwich, each combining a hint of medievalness in the contemporary choral language. Olivia Sparkhall, an alumna of the Holsts’ school in London, and like them committed to musical pedagogy, is represented by the ecstatic Lux Aeterna, blurred chords emerging from the spatially separated choirs. Perhaps most arresting are Shruthi Rajasekar’s Ushās and Priestess, specially commissioned by Corvus, which show a modern ear approaching the same Hindu texts as Holst, a hundred years later. Here the Corvus Consort really glisten, the sound bright and almost overwhelming in places. - Bernard Hughes

Add comment