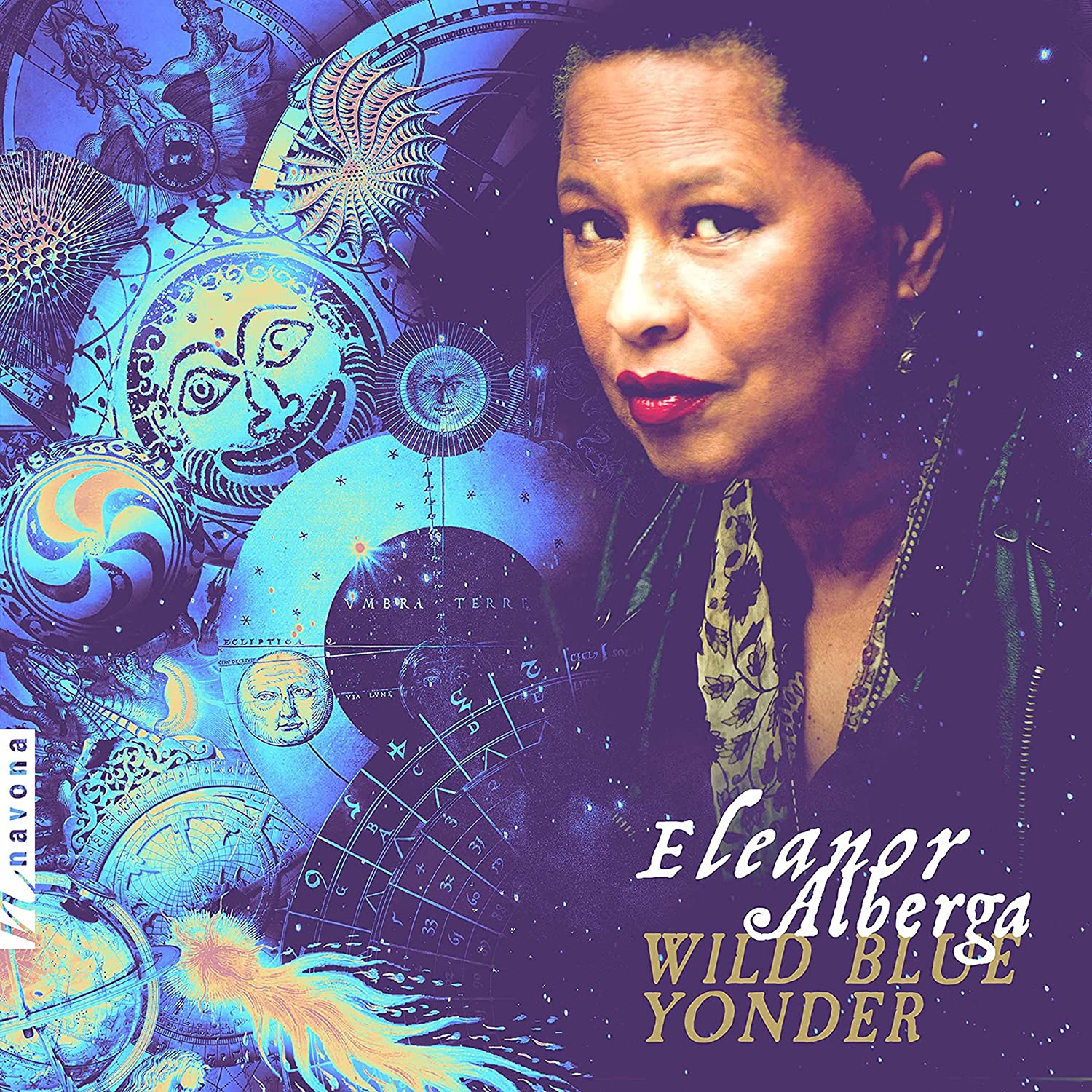

Eleanor Alberga: Wild Blue Yonder (Navona Records)

Eleanor Alberga: Wild Blue Yonder (Navona Records)

This is a belated review for an album that came out in 2021, but one well worth a retrospective appraisal. Eleanor Alberga (b.1949) is a British-Jamaican composer, perhaps best known for her 1998 setting of Roald Dahl’s version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. She has also had a successful career as a pianist as well as composer, and is an important figure in the British musical landscape. The opening and closing tracks are duets for violin and piano, featuring the composer as performer alongside her husband, Thomas Bowes. The opener, No-man’s-land lullaby, which dates from 1997, explores the imagery and landscape of the First World War. It is a meditation on a famous lullaby tune, the rhapsodic violin part a distant cousin of Vaughan Williams’s lark, sometimes taking wing with a similar soaring intensity, at other times inward and reflective. The finale, The Wild Blue Yonder, is more varied, more restless and fragmented. There is a spikiness that is characteristic of Alberga’s music, an uncompromising directness of expression, a refreshing energy. I like the way the instruments often seem to be rolling in parallel, not always in concert – until the final minutes, which dissolve beautifully.

In between, Richard Watkins (horn) leads the way in Shining Gates of Morpheus, and Nicholas Daniel (oboe) does the same in Succubus Moon, both accompanied by the string quartet Ensemble Arcadiana. In the first, Watkins conveys nobility and also the drowsiness of sleep, the strings sinking inexorably. In the second, Daniel is both sinister and persuasive, his tone exquisite. I’m a big fan of Alberga’s music and this is a good place to start – as is the 2019 disc of her first three string quartets, previously covered in this column. - Bernard Hughes

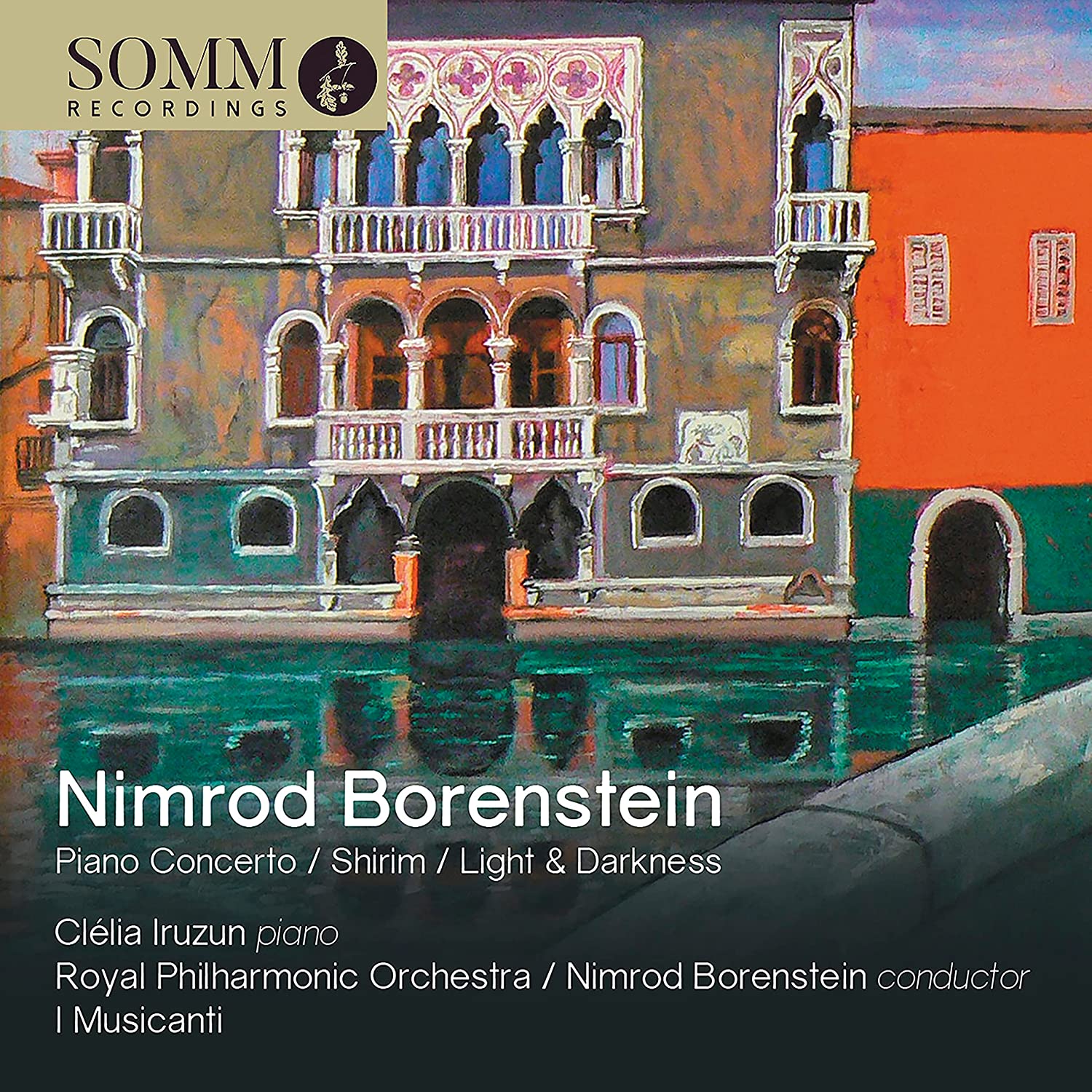

Nimrod Borenstein: Piano Concerto, Shirim, Light and Darkness Clélia Iruzun (piano),Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Borenstein, I Musicanti (Somm)

Nimrod Borenstein: Piano Concerto, Shirim, Light and Darkness Clélia Iruzun (piano),Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Borenstein, I Musicanti (Somm)

Nimrod Borenstein describes this collection as a celebration of enduring musical relationships, and his large-scale Piano Concerto is performed here by long-term collaborator and dedicatee Clélia Iruzun, who gave the first performance in Sao Paulo in 2021. Borenstein’s technical fluency can overwhelm on first hearing: in the opening movement, allusions to the romantic concerto tradition come thick and fast, making one curious as to whether we’re hearing his true voice. It’s dizzying, exciting music, but what’s it saying. The slow movement’s wistfulness sounds much more personal, the hints of grit beneath the smooth surfaces genuinely unsettling. The fast finale is a blast, with a crowd-pleasing coda. Looking for an entertaining, melodic contemporary piano concerto? Start here. Iruzun’s playing is flamboyant in all the right ways, and Borenstein’s Royal Philharmonic sound as if they’re having fun.

Though I’d suggest that the couplings give a better sense of what Borenstein can do. The piano quintet Light and Darkness takes its title from a Stefan Zweig quote, it’s a musical attempt to capture the sense of a long life lived to the full, peaks and troughs included. Anguish and ecstasy co-exist, the work lasting little more than nine minutes, and as with the concerto, the fluency really serves the music, the piano never overwhelming the string quartet. Iruzun and the members of I Musicanti play with sensitivity, Iruzun also the soloist in the 18 miniatures which make up Shirim. Borenstein describes the collection as “my own songs without words”, and these musical portraits of lost hedgehogs, puddles and nocturnal strolls are witty and affecting by turns.

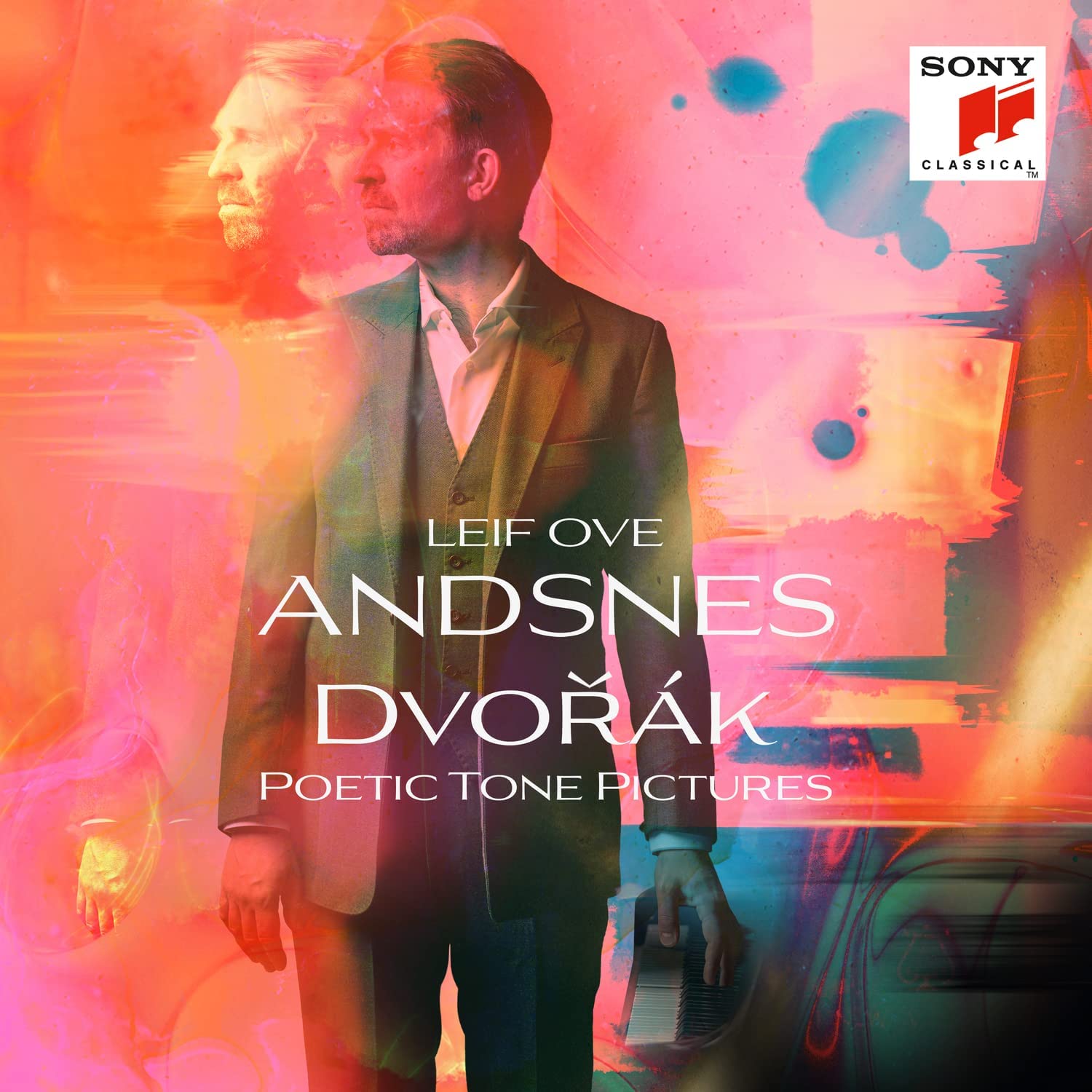

Dvořák: Poetic Tone Pictures Op. 85 Leif Ove Andsnes (piano) (Sony)

Dvořák: Poetic Tone Pictures Op. 85 Leif Ove Andsnes (piano) (Sony)

Dvořák’s first instrument was the violin: he was a competent pianist but didn’t actually own one until he was 40. Leif Ove Andsnes comments that “there are certainly places where you feel that he wasn’t a pianist”, but contemporaries noted that Dvořák was a decent player, one who didn’t “thrash around.” The 13 miniatures which make up his Poetic Tone Pictures date from 1889, shortly before the 8th Symphony. Andsnes sees them as a cycle, (see Gavin Dixon’s review), though I’d suggest that dipping into them a few at a time provides a better introduction. We’re not a million miles away from Grieg’s Lyric Pieces, Dvořak covering a similarly wide emotional and stylistic range. The opener, “Twilight Way” alternates between dreamy evocation and bounding energy, as if you’re listening to a discursive anecdote. Though Dvořák is continually entertaining, Andsnes always finding the right tone for each piece. The big-hearted folk tune of “Spring Song” is given a virtuosic left hand accompaniment, followed by a improvisatory “Peasant’s Ballad.”

He pulls out the stops in the “Furiant” and the little “Goblins’ Dance” is an earworm. The funeral march in “At a Hero’s Grave” looks ahead to the late tone poem The Wood Dove”. The closer, “In the Old Castle” features the only 5/4 time signature in Dvořák’s output, Andsnes down to a whisper in the moving final bars. Beautifully recorded too – this is a lovely disc. Next, buy Ivo Kahanek's superb 4-disc set of Dvořák’s piano music available on Supraphon; his Poetic Tone Pictures are even more idiomatic.

Joseph Haas: Reigen, Kantaten und Lieder Münchner Frauenchor/Katrin Wende-Ehmer (Chromart Classics/ TYXart) [Contains a brief scene with nudity (*)]

Joseph Haas: Reigen, Kantaten und Lieder Münchner Frauenchor/Katrin Wende-Ehmer (Chromart Classics/ TYXart) [Contains a brief scene with nudity (*)]

Here’s a curious irony: Joseph Haas (1879-1960) was one of the original founders of the contemporary music festival at Donaueschingen, and yet his own compositions stayed unwaveringly in a late romantic, artlessly tonal idiom. In his twenties Haas had made a beeline to study composition with Max Reger and thereafter never looked...forward. His main professional role in later life was as a teacher and conservatoire administrator in Munich, where his illustrious students included the composer Karl Amadeus Hartmann and the conductors Eugen Jochum and Wolfgang Sawallisch. His maxim about the purpose of music, apparently, was, "Music should delight, not offend; it should jolt, not shatter; it should dignify, not trivialise.”

This collection of songs for women’s chorus with and without piano is produced under the auspices of the Joseph Haas Gesellschaft which exists to promulgate his work. There are some gems, especially a lovely “Wiegenlied” (lullaby) sung to little wolf (sic), from the earliest collection here, composed in 1916. It is a delightful setting of a poem by Detlef von Liliencron. (According to catalogues, Rebecca Clarke also composed a song to the same words. Now that I’d love to hear…). Before we get to the “Wiegenlied” there are three “Liederreigen” (literally, round dances or "Rondes" of songs), in the dialects of three German regions, composed between 1940 and 1952. Alemannic (Switzerland and Swabia), Franconian (the area around Nuremberg) and Pfälzisch (Palatine German from the upper Rhine valley). These song sequences contain a more or less unlimited supply of jollification in the guise of huge quantities of tralala, heisasa and hopsasa.

In the past catastrophic week for choral singing, during which the BBC declared that it wants to close the BBC Singers after 99 years, we have been reminded forcibly of the high peaks of singing which a small, top-end fully professional choir can reach. The Münchner Frauenchor a group of amateurs who meet to rehearse on Mondays and are nowhere near that level, but their singing is characteristically “volkstümlich”, as befits the music. The album could well be of interest to choirs looking for more repertoire. As a continuous listen, its 76 minutes of music do sometimes run the risk of being a little bit same-y.

(*) The brief scene involving nudity is in the Franconian “Liederreigen”. In this, suitors from various professions put the case as strongly as they possibly can why the girl really would do the right to marry, say, a tailor... a cobbler… or a shepherd…or a hunter… or a farmer. The girl rejects them one by one, concluding that she intends to marry someone she actually likes. The tailor’s rejected sales patter, for the record, goes like this: “Let nobody mock tailors again / They should be honoured / Because if there weren’t any tailors/ We’d all be running around naked.” - Sebastian Scotney

Rachmaninov: Symphonic Dances, plus music by Bowen and Medtner Joseph Moog and Kai Adomeit (pianos) (Onyx)

Rachmaninov: Symphonic Dances, plus music by Bowen and Medtner Joseph Moog and Kai Adomeit (pianos) (Onyx)

One of the greatest final statements by any composer, Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances exists in a two-piano edition besides the familiar orchestral version. The work’s three movements offer a neat summation of Rachmaninov’s stylistic career, the nostalgic, very private reference to his mothballed Symphony No. 1 heard alongside music which is surprisingly sharp-edged and pungent. You can hear the influence of composers as different as Gershwin, Ravel and Stravinsky in the work, and this new two-piano recording from Joseph Moog and Kai Adomeit is crisp and punchy, accentuating the score’s percussive edge. They’re superb in the panic-stricken final minutes of the third dance, the Dies Irae vanquished by a theme first used in Rachmaninov’s All Night Vigil, and the second movement’s sleazy waltz is terrific. And are the first movement’s driving rhythms an allusion to Stravinsky’s Rite? Moog and Adomeit suggest that they could be, and they bring an irresistible poignancy to the quotation from that early symphony, now soft, tender and in a major key. Rachmaninov premiered the piece with Horowitz and was keen to record it; incredibly, RCA weren’t keen and declined the offer.

York Bowen’s late Theme and Variations for 2 Pianos popped up a few years ago on anthology from husband and wife duo Ludmilla Berlinskaya, and Arthur Ancelle, and it’s good to hear it again. Bowen’s very English-sounding theme isn’t particularly memorable but the nine variations and finale which follow are superbly entertaining. The recorded balance helps, the two pianos ideally placed. And there’s Nikolai Medtner’s Two Pieces, written during the early 1940s after the composer had moved from Russia to Golders Green. It all makes sense; Bowen had been labelled “the English Rachmaninov” and admired Medtner’s music. A sparky “Russian Round Dance” was dedicated to the pianist Edna Iles, who hosted the Medtners in Warwickshire during the early stages of World War 2. “A Knight Errant” is a brooding large-scale fantasia, deeply impressive if short on memorable tunes.

Echo: Music for voice and piano by Bach, Watkins, Purcell, Pritchard, Frances-Hoad and Wallen Ruby Hughes (soprano), Huw Watkins (piano) (BIS)

Echo: Music for voice and piano by Bach, Watkins, Purcell, Pritchard, Frances-Hoad and Wallen Ruby Hughes (soprano), Huw Watkins (piano) (BIS)

“When we perform together,” says Ruby Hughes of working with Huw Watkins, “it feels very, very easy, but also spontaneous.” It also feels as if this pair have a real instinct for finding contrasting repertoire that will really work for them both. There is palpably a chemistry and a shared purpose in their collaboration. The extensive liner note by Richard Bratby unravels some of the links across the centuries: we hear vocal Bach and folk songs through the prism of arrangements by Britten. We hear Purcell as arranged by Tippett and by Thomas Adès. There are also songs by composers of our time: a new song cycle by Huw Watkins which gives the album its title, and in which my highlight is a setting of Yeats’s “When you are old…”.

The 2012 song “Lament” by Cheryl Frances-Hoad, to words by Andrew Motion, has a wonderful arc to it, starting and ending at the borders of silence, building and then scaling down the intensity. This is a fascinatingly constructed programme. But, more importantly and above all, care, love, very great tenderness and fabulous musicianship are to be heard throughout this captivating sequence. Perhaps the best moments – and there are a lot of them – are those when we as listeners can be just transported by the sheer vocal beauty and refreshing candour of Ruby Hughes’s voice. Can Purcell’s “Music for a While” have ever been sung with more ineffable lightness than here? I doubt it. (Hughes and Watkins will be performing a very similar programme at St David’s Hall Cardiff on 28 March.) - Sebastian Scotney

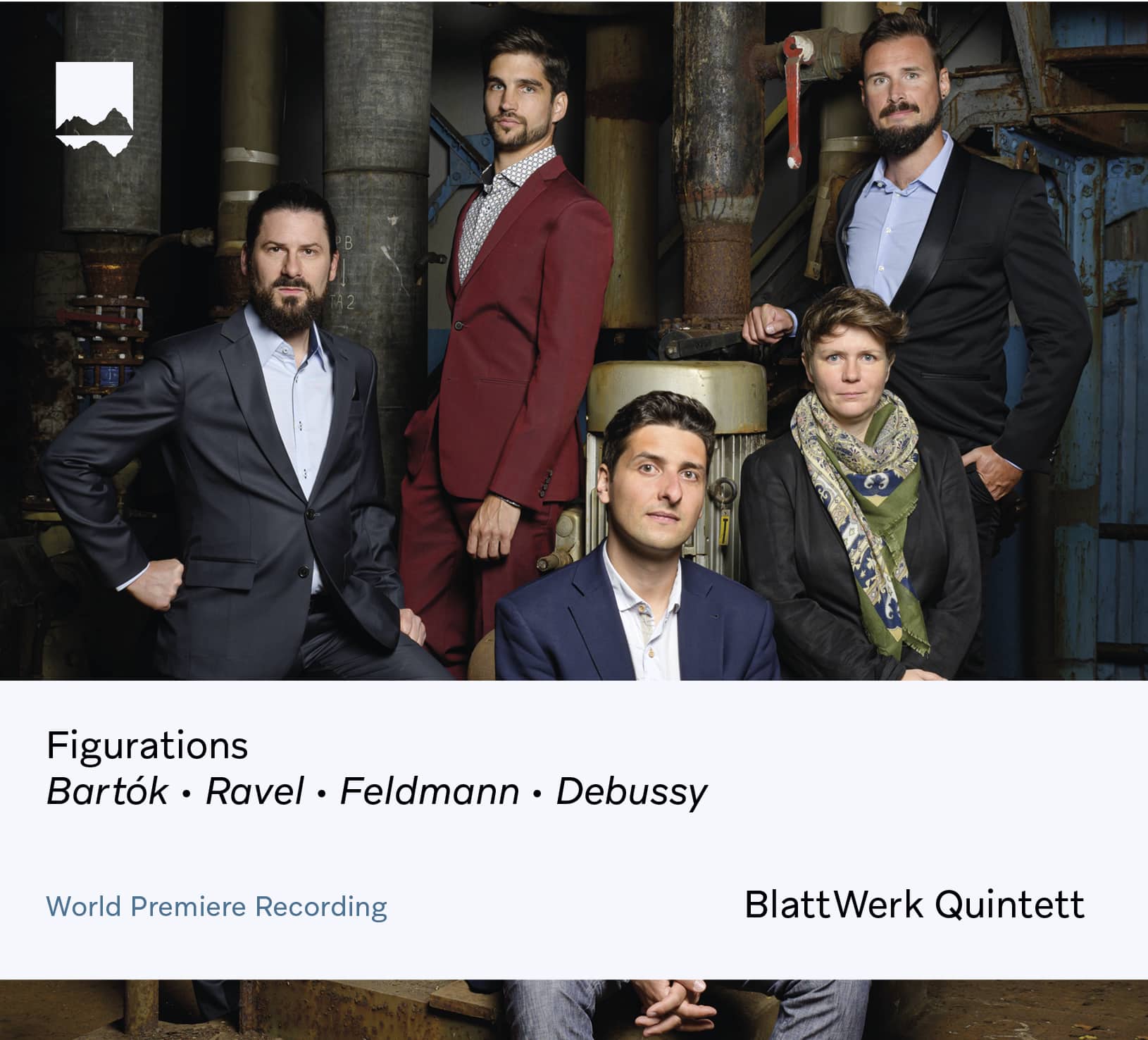

Figurations BlattWerk Quintett (Schweizer Fonogramm)

Figurations BlattWerk Quintett (Schweizer Fonogramm)

BlattWerk Quintett is styled as a reed quintet, not the normal wind quintet: comprising oboe, two clarinets, saxophone and bassoon, it jettisons the more mellow flute and horn in favour of the punchiness of the sax. As a fresh line-up the group has had to “build up our own, new repertoire and anchor ourselves in a still young musical tradition.” This means mostly using bespoke arrangements (some by members of the group) and commissioned compositions to explore this unique sonority. There are several arrangements of Ravel’s Ma Mère l’Oye out there for standard wind quintet – the piece clearly works for this kind of combination – but arrangers Elise Jacoberger and Jonas Tschanz are slightly battling against the odds in movements like “Laideronette”, whose high figuration really cries out for the flute. In other places, like “Les entretiens de la Belle et de la Bête” the lower tessitura allows the “beastly” middle section to have a real fruitiness. The flexibility of having the two clarinets cover between them the normal B-flat as well as bass and E-flat instruments means the sound of the ensemble is constantly shifting, and there is a deep, woody warmth about the final movement, “Le Jardin féerique”.

The pieces that bookend the album are delightful. Bartók’s Suite op.14 leaves me feeling I should listen to more Bartók, as listening to Bartók always does. The arrangement, by Richard Haynes, one of the clarinettists, does a great job of transferring the very pianistic textures of the solo piano original into something different but recognisably of the same character. Debussy’s Suite Bergamasque also ventures from the original in places, more broadly melodic than the Bartók, emphasising the clean outlines of the music that can get submerged by a pianist’s pedal. The biggest single piece is Walter Feldman’s figurations de mémoire, whose 14 minute duration explores complex metrical overlaps and a harmony that flirts with consonance only to shy away. It has echoes of all the other composers represented while being something more explicitly contemporary. The playing throughout is hard to fault and the sound is beautifully captured by Fréderic Angleraux, credited in the booklet for “Künstlerische Aufnahmeleitung”: “artistic recording direction”. - Bernard Hughes

Add comment