Stewart Goodyear: Callaloo, Piano Sonata; Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue Stewart Goodyear (piano), Chineke! Orchestra/Wayne Marshall (Orchid Classics)

Stewart Goodyear: Callaloo, Piano Sonata; Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue Stewart Goodyear (piano), Chineke! Orchestra/Wayne Marshall (Orchid Classics)

Callaloo is Stewart Goodyear’s indecently entertaining suite for piano and orchestra, the title referring to a mixture of diverse elements. Goodyear alludes to having grown up in a polyglot, multicultural Toronto, also taking inspiration here from his Trinidadian heritage. Specifically a recent encounter with the country's Carnival tradition (“I was exposed to Calypso music for two weeks straight, riveted every second”). Visceral excitement aside, you're won over by how seamlessly Goodyear integrates sophisticated classical elements into the music. Think late Gershwin. Driving string ostinati push “Mento” forward, and there's more rhythmic fun to be had in a very mellow middle movement. Best is the effervescent closer, “Soca”, music which deserves a Proms outing. You're left marvelling at exactly how Goodyear managed to actually notate this stuff, and at the insouciant virtuosity with which he and Wayne Marshall’s Chineke! Orchestra attack the music. Anyone in need of an energy boost need look no further. Goodyear’s youthful Piano Sonata is a precocious attempt “to pull out the stops and create the most difficult piano work ever composed”. As with Callaloo, there's a brilliant mingling of serious and popular elements, the music’s technical difficulties never getting in the way of the fun.

Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue makes for a neat closer. Goodyear suggests that this work is another callaloo, fusing 1920s popular music with klezmer and blues. Sensibly, he and Marshall opt for the original jazz band version in one of the most enjoyable modern accounts I've heard. Fast, ferocious and brilliantly characterised, the big tune’s reprise is totally free of bombast. An enjoyable collection.

Nielsen: Symphonies 3 & 5 London Symphony Orchestra/François Huybrechts, L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande/Paul Kletzki (Decca Eloquence)

Nielsen: Symphonies 3 & 5 London Symphony Orchestra/François Huybrechts, L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande/Paul Kletzki (Decca Eloquence)

Nielsen's symphonies are almost standard repertoire now, but this disc take us back to a time when they were real rarities. I can dimly remember spotting Paul Kletzki’s Nielsen 5 LP in a charity shop years ago, kicking myself ever since for not having bought it. Several decades on, it's a joy to finally hear the performance, Kletzki having succeeded Ernest Ansermet at the helm of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande in 1967. That the players sound so at ease with the work is testament to Kletzki's skills as an orchestral trainer: this is a thoughtful, very exciting performance. Very Gallic-sounding bassoons at the symphony's start signal that we're in for something special; Decca's spectacular sound adds to the impact. I've heard crazier snare drum cadenzas, but the sense of relief when it's vanquished is glorious, Kletzki's principal clarinet unmatched at the movement's close. Nielsen's dizzying finale stretches these players to the limit, Kletzki’s swiftish tempi making the closing pages overwhelming. This is one of the great symphonic endings, all the better for Nielsen's refusal to wallow in the music’s triumph. Kletzki does it justice.

The coupling is rarer still, one of a handful of recordings made by the Belgian conductor François Huybrechts. Though a prize-winner at the inaugural Dmitri Mitropoulos Conducting Competition, extensive Googling reveals no trace of what happened to Huybrechts or where he is now. Please drop me a line if you know. His 1974 account of Nielsen's glorious Sinfonia Espansiva also boasts resplendent engineering, plus incisive playing from a London Symphony Orchestra familiar with the Nielsen idiom. Alas, the first movement is far too weighty for comfort, suggesting a first run-through rather than a performance. The finale is similarly ponderous, Huybrechts’ sudden burst of energy near the close coming too late to convince. A real pity, as the middle movements are beautifully done, with Felicity Palmer and Thomas Allen as starry offstage vocalists. The quirky scherzo is deliciously spiky. A curio, then, but still worth hearing. Buy this disc for the Kletzki – it's a wowzer.

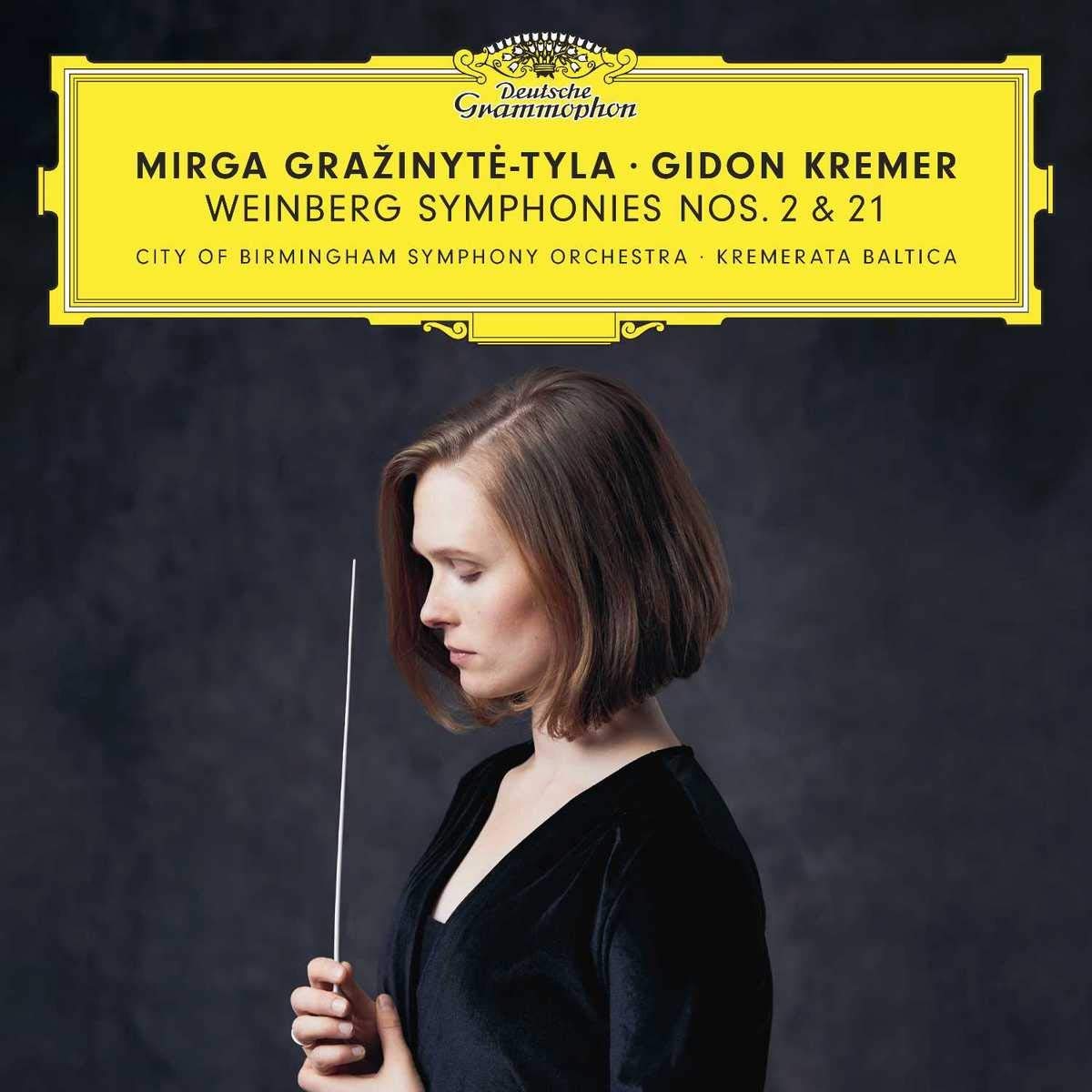

Weinberg: Symphonies 2 & 21, “Kaddish” Kremerata Baltica, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, with Gidon Kremer (solo violin) (DG)

Weinberg: Symphonies 2 & 21, “Kaddish” Kremerata Baltica, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra/Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, with Gidon Kremer (solo violin) (DG)

Weinberg's 21st symphony was the last major work he completed before his death in 1996, a vast, unwieldy single-movement work which had occupied him for several decades. Dedicated “to the memory of those who were murdered in the Warsaw Ghetto”, it's a brilliant summing up of Weinberg's strengths as a composer. This symphony should make sensitive listeners weep and wince, Weinberg deploying his vast orchestral resources with rare skill. Savage tutti outbursts nestle alongside extended passages of chamber music. Like Shostakovich, Weinberg makes haunting use of material which would sound trite in lesser hands. Clarinettist Oliver Janes throws in a jaw-dropping snatch of klezmer in the symphony’s slow third section, Weinberg segueing abruptly into an aggressive stomp of a dance. And the haunting “Andantino” which follows, xylophone and solo violin (Gidon Kremer) turning a naïve, childlike melody into something profoundly unsettling. And, my goodness, the cry of despair which kicks off the slow final section. It's incredibly moving, only topped by conductor Mirga Gražinytė-Tyler’s wordless soprano contribution a few minutes later. This performance has a unique emotional charge, Gražinytė-Tyler’s CBSO augmented by Kremer's Kremerata Baltica in what was audibly a labour of love for all involved. Kremer writes that encountering this symphony was “as if one had discovered Mahler's 11th… a musical monument that sets to music one of the greatest tragedies of the 20th century.” Believe the hype.

Weinberg’s strings-only 2nd Symphony was completed in 1946. This limpid, lyrical music exudes cautious optimism, composed shortly before state-sanctioned anti-Semitism threatened Weinberg's existence in his newly-adopted USSR. Reach the soft final bars and weep, and marvel at how beautifully Kremer's chamber orchestra captures the symphony’s varied moods under Gražinytė-Tyler’s baton. One of the most important orchestral releases of the year.

Add comment