Kudos, first, to Edward Gardner for mastering a rainbow programme of 21st century works in his first season as the London Philharmonic Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. Three Americans and a Berlin-based Brit, two women composers and two men, one of them a Pulitzer Prize-winning Afro-American who wrote the work in question in his nineties, all had the benefit of committed, clearly well-prepared performances, enthusiastically received by an ideally mixed audience.

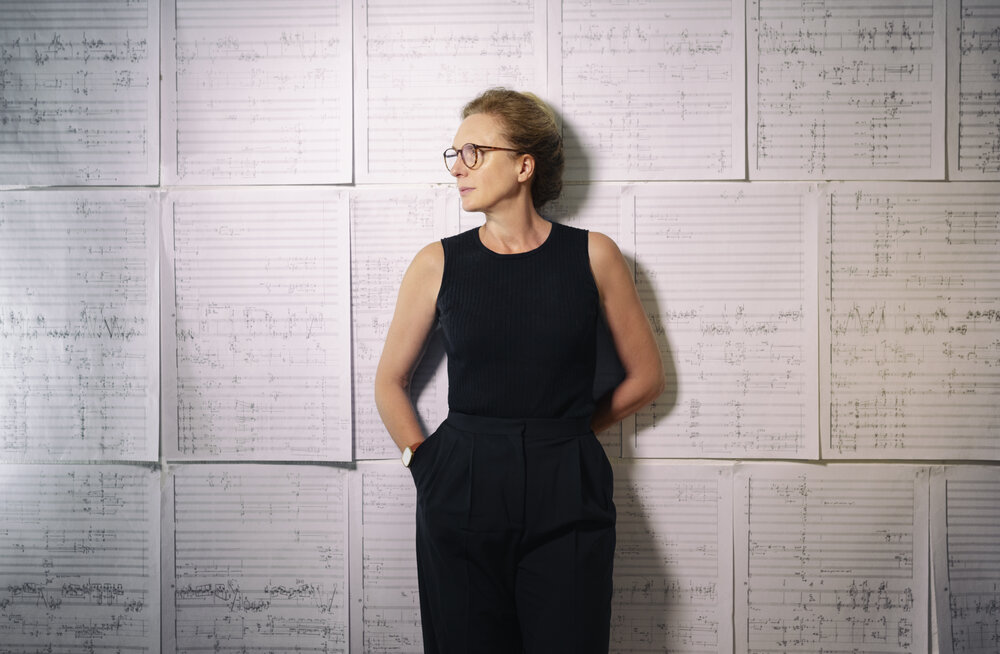

The concert kicked off a five-day Southbank Centre celebration of new and newish music from around the world, SoundState (though oddly none of the other events was so much as mentioned in the LPO programme). It’s a catch-all title, though its related cliché of a word, “soundscape”, sets alarm-bells ringing in certain circumstances. I had a feeling Gardner might use it, in the first of his affable spoken introductions, about Rebecca Saunders’ musical essence (the composer pictured below by Astrid Ackermann), and he did. Saunders has quite a following which I’ve never quite got, respectful though I have to be about an austere, often painful canvas which is all about process and rarely about hooks. In other words, every piece of music should have a “soundscape”, but what about the substance?  to an utterance for piano and orchestra is at least typical Saunders plus, the foreground being the fidgety-brilliant role for the soloist, “a disembodied voice… on an uncertain quest,” as the composer puts it; “it seeks its own final silence through its own excess”. In the breathtaking hands of Nicolas Hodges, whose improvised cadenza at the two-thirds mark sounded like at least four hands at the keyboard, the essence struck me as a terrible beauty crying out to be born, but never quite making it. Harsh clusters find mostly gentler echoes from the strings between violent exclamations. There is contrast, but no detectable shape; shorn of 10 minutes, the work would make its mark more strongly.

to an utterance for piano and orchestra is at least typical Saunders plus, the foreground being the fidgety-brilliant role for the soloist, “a disembodied voice… on an uncertain quest,” as the composer puts it; “it seeks its own final silence through its own excess”. In the breathtaking hands of Nicolas Hodges, whose improvised cadenza at the two-thirds mark sounded like at least four hands at the keyboard, the essence struck me as a terrible beauty crying out to be born, but never quite making it. Harsh clusters find mostly gentler echoes from the strings between violent exclamations. There is contrast, but no detectable shape; shorn of 10 minutes, the work would make its mark more strongly.

Missy Mazzoli’s “utterance,” River Rouge Transfiguration, managed to be uncertain of tone and direction in a very brief space. While John Adams’ Short Ride in a Fast Machine hurtles purposefully, Mazzoli’s not much longer ride seems to be in a car that’s going nowhere against a not unartistic rolling backcloth, spattered with ideas that are attractive but derivative. At least it’s never for a moment the endurance test that is her opera on Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves.

Mason Bates’ Liquid Interface is a much more arresting journey through various plays of water, a lovable crowd-pleaser to follow the impressive LPO showcasing last month of Peruvian composer Jimmy López's new Piano Concerto. Bates described the programmatic context of its essence beguilingly in his First Person piece for theartsdesk; the actuality proved mostly laid-back in a good way, and this time with at least one “hook” every minute. Recording of Antarctic glaciers breaking and electronic beats flowed seamlessly with luminous orchestral sounds – full marks to the clarinet department – and on to the pointillist play of “Scherzo liquid”. Perhaps the terror of destructive waters overpowering New Orleans jazz in “Crescent City” didn’t quite overwhelm as promised, but the Adams technique of evolving an uneasy melody brought a new dimension, and the ”electronic hurricane” submerging Dixieland jazz duly hit before the cool epilogue “On the Wannsee”. Liquid Interface is a lovable crowd-pleaser; extraordinary that it’s taken 15 years to cross the Atlantic.  Gardner warned us that George Walker’s Sinfonia No. 5 (Visions) would be disconcerting (the composer pictured above by Frank Schramm). It’s not the language that’s hard to grasp but the form. Three years before his death at the age of 96, the composer had begun sketches when he learnt of the murder of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina by a young white supremacist. The response is unremittingly angsty. We expect contrasts to take hold, but the timpani strokes and the blurted fury never quite gives up, despite the attempts of the woodwind to make some lyrical headway. Maybe painful repetition is the composer’s obsessive point; and he knows when to stop. I look forward to hearing much more of Walker’s music: his own musical identity isn’t yet clear to me. But the Sinfonia made a perfect second-half contrast to the essential amiability of Mason Bates.

Gardner warned us that George Walker’s Sinfonia No. 5 (Visions) would be disconcerting (the composer pictured above by Frank Schramm). It’s not the language that’s hard to grasp but the form. Three years before his death at the age of 96, the composer had begun sketches when he learnt of the murder of nine black churchgoers in Charleston, South Carolina by a young white supremacist. The response is unremittingly angsty. We expect contrasts to take hold, but the timpani strokes and the blurted fury never quite gives up, despite the attempts of the woodwind to make some lyrical headway. Maybe painful repetition is the composer’s obsessive point; and he knows when to stop. I look forward to hearing much more of Walker’s music: his own musical identity isn’t yet clear to me. But the Sinfonia made a perfect second-half contrast to the essential amiability of Mason Bates.

Add comment