Raven Girl, Royal Ballet/ Witch-Hunt, Bern Ballett/ The Great Gatsby, Northern Ballet | reviews, news & interviews

Raven Girl, Royal Ballet/ Witch-Hunt, Bern Ballett/ The Great Gatsby, Northern Ballet

Raven Girl, Royal Ballet/ Witch-Hunt, Bern Ballett/ The Great Gatsby, Northern Ballet

Story-ballets are back, with witches, raven girls and the all too scrutable Gatsby

Ballet is telling stories again. Last night Wayne McGregor’s debut as a narrator followed hot on the heels of Cathy Marston’s Witch-Hunt for Bern Ballett, both in the Royal Opera House complex, and Northern Ballet’s visit to London with David Nixon’s new The Great Gatsby. (To say nothing of David Bintley's Aladdin and even less of Peter Schaufuss's Midnight Express.)

Nixon is known as a straight narrative man, Marston a more expressionistic type, McGregor all abstract and kinetic, theory. Seeing the three works during the current orbit of Kenneth MacMillan’s eyepopping Mayerling at Covent Garden (now there’s storytelling) exposed that the priority for success is not “story” per se, but characters that seize you in a step, the exhilaration of expert movement, musical escape, the application of a stylised ensemble language, the suspenseful thrill of stillness. And as Balanchine said anyway, put a man and a woman on stage, and there's a story.

Of the three, Marston won out with her intelligent treatment at the Linbury Studio Theatre, for the visiting Bern Ballett, of a tale of medieval supposed witchcraft (last performance is tonight). It streaks ahead of Nixon’s expert but shallow treatment of Fitzgerald, visiting Sadler’s Wells last week, and McGregor’s lumpy, confused effort at Covent Garden with Audrey Niffenegger, Raven Girl.

McGregor’s is distant, cool, a bit of phoning home dutifully to the Royal Ballet, his heart not seeming in it

Myths are great in ballet, and Raven Girl and Witch-Hunt are both pregnant with superstitions and fairy fancies, the first a fairy-tale, the second a regrettable piece of history. But where you feel Marston urgently digging her claws into her material, McGregor’s is distant, cool, a bit of phoning home dutifully to the Royal Ballet, his heart not seeming in it.

The Raven-Girl in Niffenegger’s story is born from an unlikely marriage between a postman and a (girl) raven. The story treatment by McGregor is simplistic despite the luxury digital visuals and lush movie-score music - it’s no parable about difference, it’s no allegory about knowing yourself.

The raven girl is born to mismatched parents, feels split, asks a plastic surgeon to give her wings, then finds she can’t fly with the wings which are a lot better than her mum’s, and all is confusion after that. She wanders happily up a cliff in the dark with a raven swain, but is she now happy as all bird? And how do her odd-sock parents feel about their own life together?

Like Christopher Wheeldon’s Alice in Wonderland for the Royal Ballet, this is a work reliant on hyperactive designers while the choreographer takes a back seat. Niffenegger's charcoal palette from her book is faithfully deployed by digital whizz Ravi Deepres and designer Vicki Mortimer. There is less choreography in the inordinately long work (72 minutes) than mime and walking about, which conspires to avoid tackling the psychological life of the curious personages.

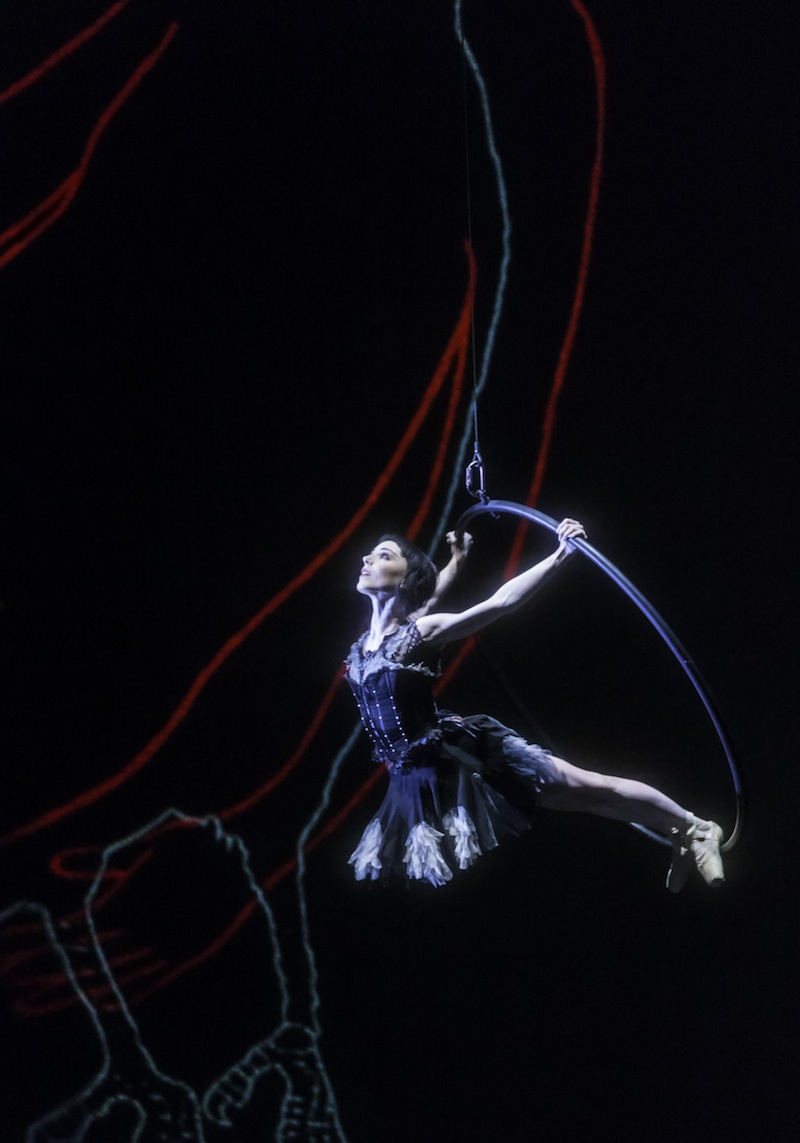

Sarah Lamb looks sweet and pliant in a black gamine wig as the Raven-Girl, and gives not a clue whether she feels pain in any part of her life, with or without wings. But she hasn’t much to play with, except for trapezes and chairs (pictured right by Johan Persson/ROH). Only two pieces of dance stand out. There's an unkindness of ravens, a corps de corbeaux, so stylishly underlit by Lucy Carter that what must be time-consumingly intricate choreography is almost invisible.

Sarah Lamb looks sweet and pliant in a black gamine wig as the Raven-Girl, and gives not a clue whether she feels pain in any part of her life, with or without wings. But she hasn’t much to play with, except for trapezes and chairs (pictured right by Johan Persson/ROH). Only two pieces of dance stand out. There's an unkindness of ravens, a corps de corbeaux, so stylishly underlit by Lucy Carter that what must be time-consumingly intricate choreography is almost invisible.

We get lift-off finally in the culminating pas de deux for the Raven Girl and the Raven Prince, who appears like magic at the end, an unexplained mystery. This makes lovely, heart-lifting attempts at launch, Lamb wafted weightlessly in her dream of flying by the supportive Eric Underwood, helped into her own fantasy through some imaginative and even erotic work by McGregor which at last sets loose something childlike and human in that oppressively cool cerebrum of his.

However, it is more rewarding to see a choreographer who you sense felt an imperative to put her characters on stage and show us their emotional lives. Cathy Marston isn’t an innovative or inventive choreographer of movement, but she has thrown all her might into Witch-Hunt. An intelligent passion for her subject runs through the work, redeeming many of its weaknesses. Her choice of 17th-century music by Vivaldi and his contemporaries offsets music created to rise above baseness against events that expose human beings’ animal fears, particularly about women and sex.

The cast, dressed in white, resemble staff at a psychiatric hospital, where an actress voices her memories of being an ailing child who came under the influence of a new servant to the household, a beautiful, alluring creature whose sexual attractiveness rapidly saw her accused as a witch. The child vomited needles; who put the needles in her milk? The servant, being a witch? The mother, both jealous of the servant and in love with her, attempting to frame her? The child herself, unhinged by her desperate sense of alienation from her mother?

Clemmie Sveaas emits a focused sensuality that illuminates why the woman was found both irresistible and suspicious

Three versions of the story play out, and Marston has talent enough to indicate a change in nuance and yet the same facts - not an easy thing to do, and it’s no surprise she can’t pull it off quite well enough to grip our emotions and lead us through the end of her 75 minutes (at least they seem shorter than McGregor’s 72). The economy of the set - a chain of bare metal frames which link together unceasingly into doors, windows, walls - works well, and the music editing has choice moments, like Vivaldi's jagged Winter from the Four Seasons when she swallows the needles.

The doubling of the pivotal child between a speaking actress and a dancer is a mistake - the text is a wordy, pretentious distraction. Paula Alonso as the dancing, pre-pubertal girl Annamiggeli lollops with a neediness and readiness to be seduced that works in character terms, even if it feels fairly primitive in dance terms. As her idol and, perhaps, exploiter, the magnetic Clemmie Sveaas emits a focused sensuality as the servant Anna Göldi that instantly illuminates why the woman was found both irresistible and suspicious.

What Marston also gestures at is the power of the ensemble in dance; she deploys her “nurses” and “citizens” in strong friezes that evoke the looming authority of the community, a tidal wave of mass disapproval that the ambiguous Anna Göldi can’t escape. But the piece overall is either too long or too short - it would be better as a 40-minute one-acter, or a two-acter with Marston more boldly loosening the limited vocabulary of her choreography to travel with her psychological interest.

Marston is a positive sophisticate compared to Northern Ballet's David Nixon, whose The Great Gatsby is undemanding numbers-ballet, with smart costumes, a light-entertainment score by the late Sir Richard Rodney Bennett and a swanky set designer, Jérôme Kaplan, who knows how to make space and light look expensive.

It passes time, but this isn’t a plot that has much scope in dance, a bore already in the literary version. George is married to Myrtle who loves Tom who’s married to Daisy who loves Jay, who’s fancied by Nick and Jordan... The lack of any dominant character interaction means that Daisy is flighty and Jay is a stuffed shirt, and it takes a determined performer like Isaac Lee-Baker as George or John Hull as Tom Buchanan to break through the fourth wall and seize one's interest in what happens to them.

You don’t need a story to tell a story if you’ve got enough steps in your toolbox

Just one more thing: on the bill with McGregor at the Royal Ballet is Balanchine’s crisp tutu ballet Symphony in C, whose exhilaratingly tricky, delicious choreography marries the teenage Bizet’s effervescent symphony with a profound joy in music that sets dance alight like a match to paper.

As if proving his point about a man and a woman being a story, last night Marianela Nuñez and Thiago Soares soared above the clunkiness of the rest of the cast to fly away in the second movement. Echoing their remarkable performance of Balanchine's Diamonds a few years back, they once again showed such glorious empathy between them, and such poise in their execution (hers in particular) that between them they created their own tale - a lesson for other choreographers that you don’t need a story to tell a story if you’ve got enough steps in your toolbox.

- Bern Ballett perform Cathy Marston’s Witch-Hunt at the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Studio Theatre tonight

- The Royal Ballet performs McGregor’s Raven Girl with Balanchine’s Symphony in C at the Royal Opera House, London, on Tuesday and Wednesday next, then 3 & 9 June

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Comments

In the book of the Raven

I enjoyed the opening