Parsifal, Royal Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Parsifal, Royal Opera

Parsifal, Royal Opera

Passing musical pleasures can't redeem a bloody betrayal of Wagner's holier intentions

Is anyone else sick of creepy brotherhoods skewering the transcendent in Mozart’s and Wagner’s late operas? Both Sarastro’s cult and the company of the grail are in sore need of change - "fresh blood" would be an unfortunate term under the circumstances - when we first encounter them.

Langridge, who along with the present design team has done fine work on the powerful myth of Harrison Birtwistle's The Minotaur, is no doubt right to insist so much on grail celebrant Amfortas’s sickbed and drip. Central, certainly, is the horror of the undead ruler, pierced and wounded by a near-fatal dalliance with the most “dangerous” of the women who live on the margins of the secret society. So it's fair enough to present the hospital room, strip-lit in another cliché of alienation shared with the ENO Flute, as an ever-present centre-stage cube which “transforms” into the heart of the ceremony supposed to bring both daily relief and never-ending torment to the man who can’t die. Only here, in the first of many false steps, it’s the act itself – blood-letting of a pubescent boy (and to hell with the spoiler) – which disgusts both Gerald Finley’s tormented Amfortas, compelled to serve the needs of wheelchair-bound bloodsucker dad Titurel (Robert Lloyd), and Simon O’Neill’s appalled novice onlooker of a Parsifal. And us, too, if we’re human: this Parsifal wasn’t the only one who wanted to run away.

Your attitude to all this will depend on whether or not you feel, as I do, that the director’s first duty is to honour the moments of grace amidst all the apocalyptic darkness – and it isn’t just a question of having a grail cup and a shining light. Langridge's repellent ritual cancels out all the good intentions in conductor Antonio Pappano’s finest half-hour-plus, his gentle pacing of Wagner’s transformation music and grail ceremony. With Pappano, though, if the sounds are always right and tell us how modern and pre-Debussyan the textures of this extraordinary endgame always are, the pacing isn’t.

Your attitude to all this will depend on whether or not you feel, as I do, that the director’s first duty is to honour the moments of grace amidst all the apocalyptic darkness – and it isn’t just a question of having a grail cup and a shining light. Langridge's repellent ritual cancels out all the good intentions in conductor Antonio Pappano’s finest half-hour-plus, his gentle pacing of Wagner’s transformation music and grail ceremony. With Pappano, though, if the sounds are always right and tell us how modern and pre-Debussyan the textures of this extraordinary endgame always are, the pacing isn’t.

It felt especially unhelpful to the long narrative of past history unfolded by René Pape’s patient Gurnemanz after the Prelude. Pape (pictured above right with O'Neill's Parsifal in Act Three) has the most beautiful of bass timbres, he inflects the meaning well, but how – for the first time in my experience – all this essential information sagged perilously in the mouth of a narrator made by Langridge an unsympathetic cult-promoter. Pape is tested, too, by the generous outbursts of the last act, where Langridge comes closer to Wagner’s intended narrative with a Good Friday cleansing of the injured, newly experienced Parsifal by the “good father” and the now Magdalenesque Kundry.

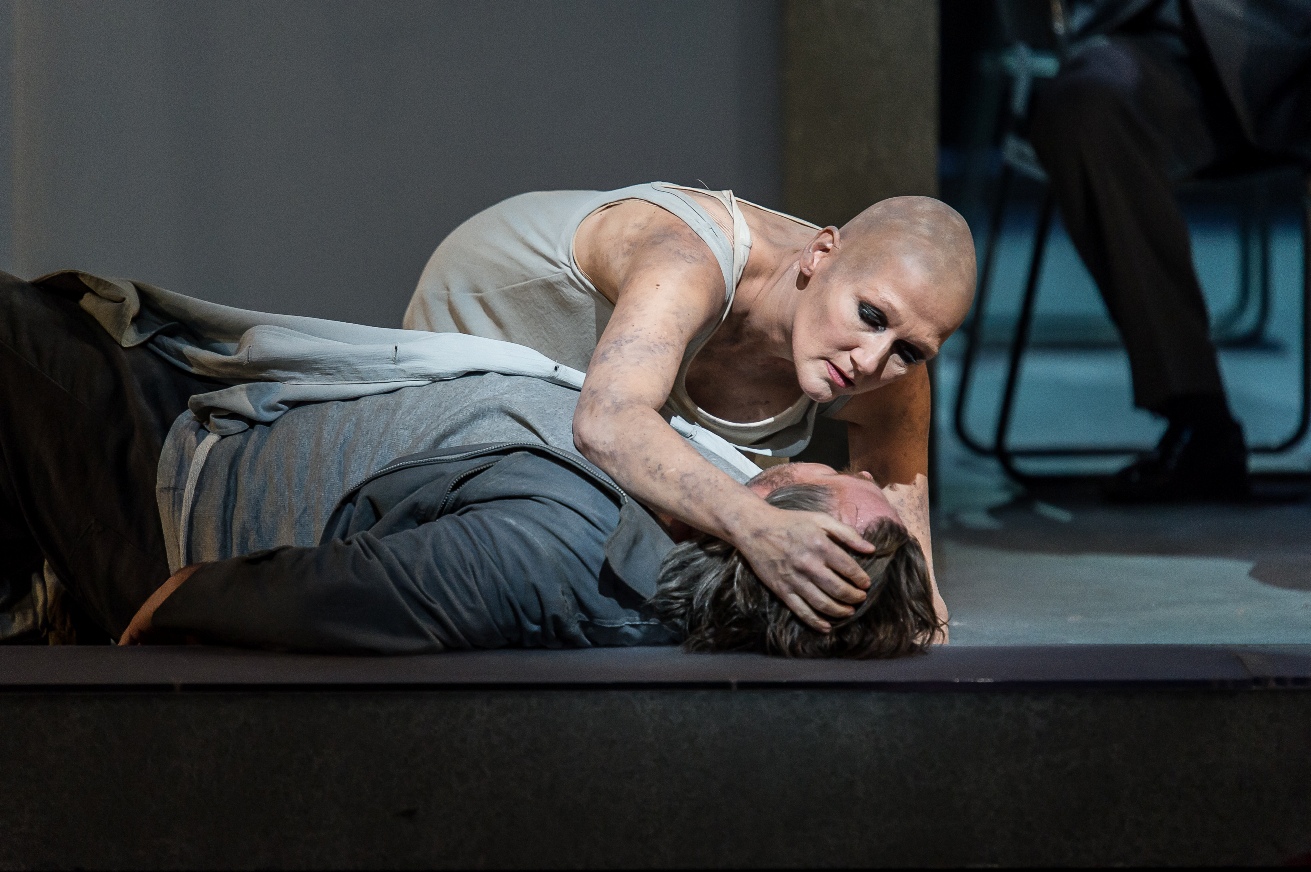

Who remains, in Angela Denoke’s dedicated interpretation, the most fascinating character in the opera: shaven-headed, dishevelled grail servant (pictured below with O'Neill in Act One), vamp under spell-bound compulsion and a woman finally restored to her noble wits. The voice isn’t exactly beautiful, there’s essentially only one colour, and it barely holds out for the final rants against a Parsifal newly aware of the weight of sin – but then the overtouted Waltraud Meier, for stage reasons alone the Kundry of choice over the past 30 years, couldn’t cut the mustard vocally there either.

It doesn’t help that Pappano is again much too slow, however beautiful and sleepy the string sound, in Kundry’s weird incestuous seduction where she takes on the role of Parsifal’s mother. The red wig is the giveaway, along with the many tableaux of What Happened Earlier played out in the cube (in Act One, where they include acolyte-gone-bad Klingsor’s self-castration, they’re no substitute for the reactions of a Kundry who should be on stage all through Gurnemanz's narrative but for some reason isn’t here).

It doesn’t help that Pappano is again much too slow, however beautiful and sleepy the string sound, in Kundry’s weird incestuous seduction where she takes on the role of Parsifal’s mother. The red wig is the giveaway, along with the many tableaux of What Happened Earlier played out in the cube (in Act One, where they include acolyte-gone-bad Klingsor’s self-castration, they’re no substitute for the reactions of a Kundry who should be on stage all through Gurnemanz's narrative but for some reason isn’t here).

With Gerald Finley’s Amfortas severely overparted and taxed to the extreme by Pappano letting his two narratives drag when at that point in each of the outer acts we want to get to the end, and Willard White’s Klingsor going through now familiar motions, it’s left to Simon O’Neill to provide the best-connected singing of the evening. He’s no great shakes as an actor, at least under Langridge; here he stumbles and totters less convincingly than everyone else, and his get-up, especially the vest in which he slays the warriors of Klingsor’s castle, isn’t flattering. But how he can pull out the stops as he realizes the significance of Amfortas’s wound after Kundry’s kiss – the production has its moment here as a second cube is unveiled with the suffering grail king revealed behind the first – and how nobly he returns the stolen spear to the brotherhood at the end. It’s just a shame that the ultimate "redemption to the redeemer" is nothing more than a Wizard of Oz moment, a dissolution which should have happened much earlier.

O'Neill also manages to be playful with the Flowermaidens of Klingsor’s enchanted garden (pictured right with O'Neill), who eventually shuck off their widows’ headscarves and do what we usually expect of them; there are some promising voices here in the mix, chiefly Anna Devin, Celine Byrne and Anna Patalong. The female chorus, too, has a chance to make more of an impression than its male counterparts, marginalised by the ritual. Alison Chitty’s designs and Paul Pyant’s lighting come into their own for the magic; either side of it, they're far too stuck with red, grey and black. So much for a forest which ought to be a sanctuary of green but consists only of leafless timber, much of it fallen in Act Three.

O'Neill also manages to be playful with the Flowermaidens of Klingsor’s enchanted garden (pictured right with O'Neill), who eventually shuck off their widows’ headscarves and do what we usually expect of them; there are some promising voices here in the mix, chiefly Anna Devin, Celine Byrne and Anna Patalong. The female chorus, too, has a chance to make more of an impression than its male counterparts, marginalised by the ritual. Alison Chitty’s designs and Paul Pyant’s lighting come into their own for the magic; either side of it, they're far too stuck with red, grey and black. So much for a forest which ought to be a sanctuary of green but consists only of leafless timber, much of it fallen in Act Three.

So Act Two, as usual with directors who don’t know what to make of the essential holiness, works best. Nor is its short Prelude scuppered like its counterparts in the outer acts - the first with a video image of Kundry's mouth - laughing at Christ, presumably - which has nothing to do with the music that's unfolding, the last with the deracination of the grail community when the strings speak of Parsifal's endless wanderings. The uncomfortable truth remains that with a grail gathering that’s the exact opposite of what Wagner intended – and it’s one of the few elements in the mystifying drama where we can be sure, however vaguely, that he intended celestial good - this evening, for all its fleeting musical pleasures, falls at the first hurdle.

- Parsifal at the Royal Opera until 18 December with a live screening on the last night

- David Nice presents Building a Library on Parsifal on BBC Radio 3's CD Review, 14 December

- More about Parsifal on David Nice's blog, I'll Think of Something Later

- Introducing The Wagner Interviews, a series of video conversations with eminent Wagnerians

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Comments

Very detailed and informative

Agreed, Joe. I think Michaela

Agreed, Joe. I think Michaela Schuster is probably heading to the top of the list, too. I saw her at the beginning of her career in a Graz Parsifal (directed by David Alden) which seemed to me to hit every target.

Excellent review. I thought

OK - we get that you didn't

Very well argued

Very well argued rationalisation, Tim, thank you. I get what you're getting at and possibly Langridge too. And I'm absolutely in favour of new productions opening up fresh possibilities so that one says, "I never saw the music in that light". But I think there has to be a novel approach to what's actually there (Richard Jones has shown us that time and again).

Surely, though, the music of the grail ritual around Amfortas's anguish - and I have a problem with the knights' chorus later on - is pure light, and can't be contradicted by something shocking and sick. I hadn't grasped the significance of the reappeared Christ figure at the end - it wasn't made clear enough in the action, and throughout I couldn't see from far back what the knights were doing to their hands, or sometimes what objects they were carrying or giving to each other - but I still don't think it serves as a post hoc rationalision of a horrible rite. Amfortas going off with Kundry, yes, I liked that. But the means didn't justify the end for me.

I'm all for updates-Richard

I went to see this live

Just seen it at the cinema. I