theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Singer Sir Thomas Allen | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Singer Sir Thomas Allen

theartsdesk Q&A: Opera Singer Sir Thomas Allen

This week the great lyric baritone celebrates his 40th anniversary role at Covent Garden as Don Alfonso

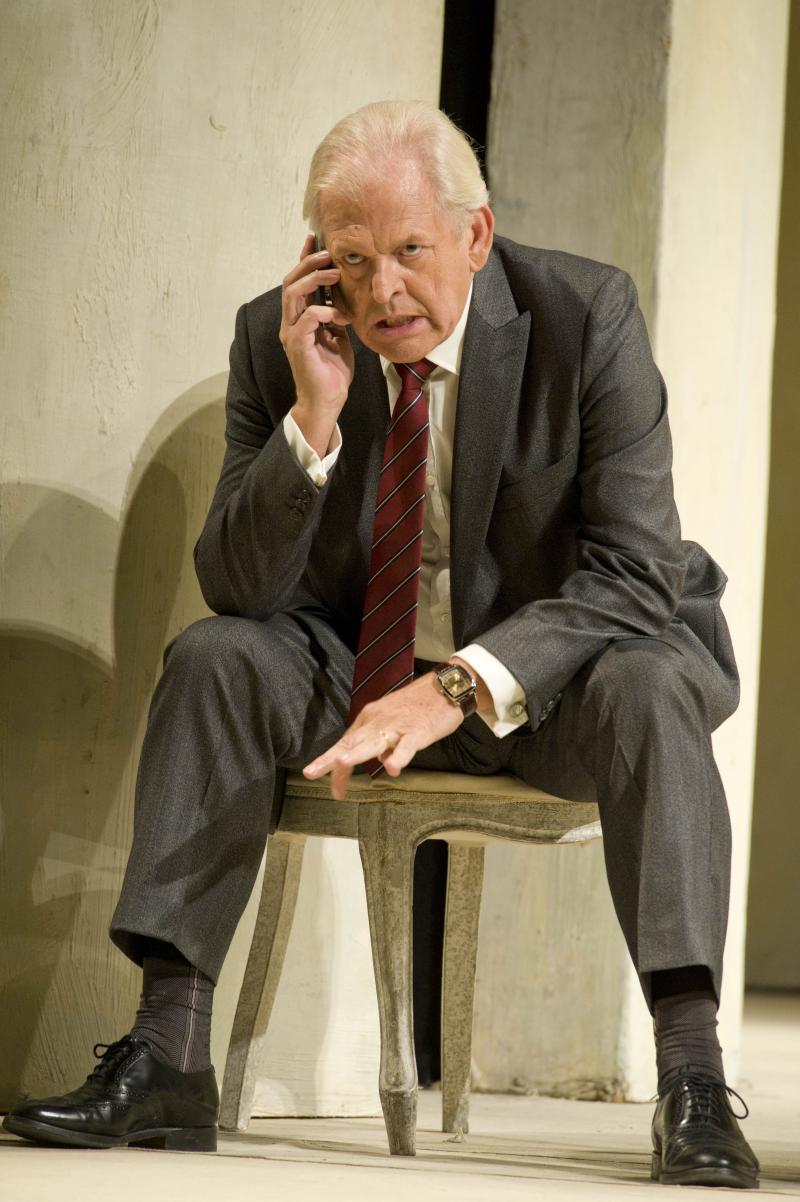

The landmarks continue to mount for Sir Thomas Allen (b. 1944). Awarded the CBE 22 years ago and knighted a decade later, the great lyric baritone notched up his 50th role at Covent Garden in 2009 and this week in Cosi Fan Tutte he celebrates 40 years with the Royal Opera House. In the same week he takes up his new appointment as Chancellor of the University of Durham. Indeed, although he has sung everything from Monteverdi to Onegin to negro spirituals, in his speaking voice he remains a son of County Durham. The first consonant of "opera" is unstressed to the point of inaudibility.

In a career ranging across languages, centuries and continents, the one constant has been his great gift for inhabiting a role not only as a singer but also as an actor. And he is still producing novelties. IN 2008, bizarrely under the direction of Woody Allen, he added Gianni Schicchi to his repertoire. In 2009 he sang alongside the voice of Stewie from Family Guy in the Proms’ tribute to the great MGM musicals. In a wide-ranging interview he talks to theartsdesk about a life spent in Covent Garden and beyond.

JASPER REES: So in your 40th year you've sung more than 50 roles at the Royal Opera House.

SIR THOMAS ALLEN: I’ve no idea. Somebody is keeping count around here, one of the trainspotters. They range from five-hour operas to a minute-and-a-half appearance.

What was that?

I think it was a Scythian in Iphigénie en Tauride. He comes on and gives a weather report and goes off again. It’s a very, very brief appearance.

Same pay?

Same pay?

Well, at that time when you’re a member of the company they’ve got you, you’re in hock to them so you just do it. You can take the night off if you wanted to as well. It works the same way. No, I think we’ve jointly had our money’s worth over the years. Can’t complain. Swings and balances.

If someone had told you in 1971 that in very nearly 40 years you would be singing your 50th role at the Opera House, what would have been your reaction?

Well, there would have probably been several reactions. If they’d told me it would be Faninal in Rosenkavalier I might have stopped right then (Pictured above right: Sir Thomas Allen as Faninal in Der Rosenkavalier © ROH / Mike Hoban). I was talking to a colleague of mine and said, “It’s one of those roles that’s quite tricky and engages the brain - what remains of it - and it would be nice if I were coming to it now, revisiting it after 20 years.” And he said, “Come on, be honest, if 20 years ago you’d been offered the role of Faninal, what would your gesture have been?” And so I made a rude Italian gesture, because that’s the truth.

Which one?

It involves a hand and an arm. Hopefully the arm is not false and goes flying over your shoulder. But no, I’d have been amazed. I remember just shortly before 1971 I used to sing a lot of concerts around the country and people would say, “Ooh, when you’re singing your first role at Covent Garden we must have tickets. Let us know when it’ll be.” And I thought they were talking to someone else. It’s been a journey of amazement really. I had no idea that what has happened in my life would have taken place. It’s all come as a big surprise.

Was it in any shape or form an ambition to have this kind of career? Would you not have had the gumption to form such a grand ambition?

I wouldn’t have had the gumption because I didn't know the nature of a music career or a singing career. I grew up in Seaham, a mining community in Durham. There weren’t many opera singers came out of my town. There were local singers but you didn't do it for a job. If you were in the local grammar school, you got through the 11-plus - which is what I did – you then went on to college or university or whatever it might be. We had a headmaster who actually encouraged you to graduate away from that community. He wasn’t mad on it, I look back in reflection now. He wanted us all to widen our prospects and horizons and see the rest of the world. I remember looking at newsreels at the pictures and seeing a big aeroplane arriving in London somewhere – probably it was still Croydon, I’m not sure – and a man called Beniamino Gigli getting off the plane because he was coming for the London season. And that was it. That doesn’t register. He might as well have been from Saturn or Neptune somewhere. It was that foreign, the concept. I had never imagined what that life must be, who this man was, and what was going on in a theatre such as this.

I was very lucky in several senses. Singing in general then had more street credibility than it seems to have now

And that was the case for quite a long time. I had no idea. Certainly at the age of 16 – I think it was around about then – I went to see at Sunderland Empire the Sadler’s Wells Company on tour performing Tosca. But even then I wasn’t curious or inquisitive enough to investigate what that was. We didn’t listen to the Third Programme at home. It was either Radio 4 or Radio 2. Two-Way Family Favourites on Sunday, that was it.

Did Tosca grab you by the lapels?

Yeah, it did. It made a big impression. In fact I got to know two of the people. The Tosca I got to know a few years after that and the Cavaradossi became a very good friend of mine some way down the line. It was Victoria Elliott who was a big star then, and a Welsh tenor, tough little fella, called Bob [Robert] Thomas who took an interest with his daughter once in a pottery class. She gave it up, he took it on and he became a potter. His career petered out. He was a tough, outspoken individual but I liked him very much and he made great pots. And he was also a very very fine singer. A colleague of mine – we were talking about him once quite a lot of years ago now – and he said, "Bob Thomas was the nearest thing I heard to Caruso” is what he said, which is rather extraordinary. Anyhow, that was the memory.

How much do you remember about that first production?

The first thing I did here was to understudy Onegin, which was early days for as big a role as that for me, but I got to know that cast who have been friends, those that survive, ever since. So that was memorable and that was a production that I went into rather further down the line with Peter Hall. I remember my first appearance onstage which was as Donald in Billy Budd and I understudied Peter Glossop as Billy Budd. And I can still remember standing on the stage for the first time, as opposed to the London Opera Centre where we did the early rehearsals. Standing on the stage one morning it was dark, and I think we came to a break in the morning’s rehearsal and the lights, the little candles, came on around the theatre and sentimental old me felt a tear gathering in my eyes. And I cried. It was an amazing thing to witness, to see this most beautiful theatre and to be involved in it, not knowing how long that involvement might last.

The first thing I did here was to understudy Onegin, which was early days for as big a role as that for me, but I got to know that cast who have been friends, those that survive, ever since. So that was memorable and that was a production that I went into rather further down the line with Peter Hall. I remember my first appearance onstage which was as Donald in Billy Budd and I understudied Peter Glossop as Billy Budd. And I can still remember standing on the stage for the first time, as opposed to the London Opera Centre where we did the early rehearsals. Standing on the stage one morning it was dark, and I think we came to a break in the morning’s rehearsal and the lights, the little candles, came on around the theatre and sentimental old me felt a tear gathering in my eyes. And I cried. It was an amazing thing to witness, to see this most beautiful theatre and to be involved in it, not knowing how long that involvement might last.

The sense of arrival was palpable.

It was. And surprising too because I had never planned to be involved in opera. I didn’t train to be an opera singer. I had no stage craft at all. I had to pick it up as I went along. I trained to be a singer.

What were the circumstances in which you gravitated towards the other discipline?

Money. I had to make a living.

You studied oratorio and Lieder first.

That was my life at the Royal College [of Music].

Was there an option to study opera?

I could have gone into the opera school. It didn’t have a great reputation at the time and I didn’t see myself doing it until some years down the line. I still towards the end, my last year there, saw myself as being principally a singer of recitals and oratorio as well, and occasionally making it to an opera house. And then I got the opportunity, because a baritone went missing – he took a job and was gone – they needed a baritone and I was the best one going upstairs in the rest of the college. I was approached and said I would do it. It might be good experience. So I did, I went downstairs and did one opera.

Which was what?

It was The Prima Donna by Arthur Benjamin, which I haven’t actually sung since, and nor has anyone else as far as I know.

Below: Sir Thomas Allen as Music Master in Ariadne auf Naxos, 2002 © Bill Cooper/Royal Opera House

However, it must have turned on a light.

However, it must have turned on a light.

Oh, it did. I enjoyed it. I felt an affinity with the stage. I couldn’t do my make-up and I didn’t do my make-up for quite some time - I hadn’t learnt anything of that sort. But the director of it recognised that I had a facility around the stage which was in a very raw state and could be developed and it went on from there.

Had you as a grammar school boy in County Durham already discovered a facility for stage acting?

No. I carried a gun in The Devil’s Disciple. I could march because I was in the church lads’ brigade but speaking verse, rhyming couplets or whatever else – it was usually Shakespeare we did at school – I had nothing to do with. I didn’t get onstage. I rather wish I had.

Not even to sing?

To sing I did.

How good a singer were you as a teenager at, say, 15?

Exceptional.

How good were you before your voice broke?

I was a good boy singer. I was head chorister in the church. But my voice didn't take time to break. I was head chorister at a practice one Thursday night and the following Thursday something happened in that week in between which I didn’t notice but they took the ribbon off me and I went and joined the men in the back row and sang the bass line. I went straight from treble to baritone. And I continued singing through school.

Were you individually tutored?

I was very lucky in several senses. Singing in general then had more street credibility than it seems to have now. We had a school choir and we all enjoyed that. And at the end of the year there would be a school concert, we’d sing choruses from Messiah or The Creation or whatever it might be. There was always the need for a soloist. There was always the recorder group and the school orchestra in which the French master played flute. It wasn't a great orchestra but I played an organ solo, I remember, and also sang a solo. I offered up a song which I sang and it clearly registered. And it was my physics master who played for me – Renaissance man personified – and then offered to give me lessons. I started lessons as a 15-year-old at school.

The landmarks continue to mount for Sir Thomas Allen (b. 1944). Awarded the CBE 22 years ago and knighted a decade later, the great lyric baritone notched up his 50th role at Covent Garden in 2009 and this week in Cosi Fan Tutte he celebrates 40 years with the Royal Opera House. In the same week he takes up his new appointment as Chancellor of the University of Durham. Indeed, although he has sung everything from Monteverdi to Onegin to negro spirituals, in his speaking voice he remains a son of County Durham. The first consonant of "opera" is unstressed to the point of inaudibility.

In a career ranging across languages, centuries and continents, the one constant has been his great gift for inhabiting a role not only as a singer but also as an actor. And he is still producing novelties. IN 2008, bizarrely under the direction of Woody Allen, he added Gianni Schicchi to his repertoire. In 2009 he sang alongside the voice of Stewie from Family Guy in the Proms’ tribute to the great MGM musicals. In a wide-ranging interview he talks to theartsdesk about a life spent in Covent Garden and beyond.

JASPER REES: So in your 40th year you've sung more than 50 roles at the Royal Opera House.

SIR THOMAS ALLEN: I’ve no idea. Somebody is keeping count around here, one of the trainspotters. They range from five-hour operas to a minute-and-a-half appearance.

What was that?

I think it was a Scythian in Iphigénie en Tauride. He comes on and gives a weather report and goes off again. It’s a very, very brief appearance.

Same pay?

Same pay?

Well, at that time when you’re a member of the company they’ve got you, you’re in hock to them so you just do it. You can take the night off if you wanted to as well. It works the same way. No, I think we’ve jointly had our money’s worth over the years. Can’t complain. Swings and balances.

If someone had told you in 1971 that in very nearly 40 years you would be singing your 50th role at the Opera House, what would have been your reaction?

Well, there would have probably been several reactions. If they’d told me it would be Faninal in Rosenkavalier I might have stopped right then (Pictured above right: Sir Thomas Allen as Faninal in Der Rosenkavalier © ROH / Mike Hoban). I was talking to a colleague of mine and said, “It’s one of those roles that’s quite tricky and engages the brain - what remains of it - and it would be nice if I were coming to it now, revisiting it after 20 years.” And he said, “Come on, be honest, if 20 years ago you’d been offered the role of Faninal, what would your gesture have been?” And so I made a rude Italian gesture, because that’s the truth.

Which one?

It involves a hand and an arm. Hopefully the arm is not false and goes flying over your shoulder. But no, I’d have been amazed. I remember just shortly before 1971 I used to sing a lot of concerts around the country and people would say, “Ooh, when you’re singing your first role at Covent Garden we must have tickets. Let us know when it’ll be.” And I thought they were talking to someone else. It’s been a journey of amazement really. I had no idea that what has happened in my life would have taken place. It’s all come as a big surprise.

Was it in any shape or form an ambition to have this kind of career? Would you not have had the gumption to form such a grand ambition?

I wouldn’t have had the gumption because I didn't know the nature of a music career or a singing career. I grew up in Seaham, a mining community in Durham. There weren’t many opera singers came out of my town. There were local singers but you didn't do it for a job. If you were in the local grammar school, you got through the 11-plus - which is what I did – you then went on to college or university or whatever it might be. We had a headmaster who actually encouraged you to graduate away from that community. He wasn’t mad on it, I look back in reflection now. He wanted us all to widen our prospects and horizons and see the rest of the world. I remember looking at newsreels at the pictures and seeing a big aeroplane arriving in London somewhere – probably it was still Croydon, I’m not sure – and a man called Beniamino Gigli getting off the plane because he was coming for the London season. And that was it. That doesn’t register. He might as well have been from Saturn or Neptune somewhere. It was that foreign, the concept. I had never imagined what that life must be, who this man was, and what was going on in a theatre such as this.

I was very lucky in several senses. Singing in general then had more street credibility than it seems to have now

And that was the case for quite a long time. I had no idea. Certainly at the age of 16 – I think it was around about then – I went to see at Sunderland Empire the Sadler’s Wells Company on tour performing Tosca. But even then I wasn’t curious or inquisitive enough to investigate what that was. We didn’t listen to the Third Programme at home. It was either Radio 4 or Radio 2. Two-Way Family Favourites on Sunday, that was it.

Did Tosca grab you by the lapels?

Yeah, it did. It made a big impression. In fact I got to know two of the people. The Tosca I got to know a few years after that and the Cavaradossi became a very good friend of mine some way down the line. It was Victoria Elliott who was a big star then, and a Welsh tenor, tough little fella, called Bob [Robert] Thomas who took an interest with his daughter once in a pottery class. She gave it up, he took it on and he became a potter. His career petered out. He was a tough, outspoken individual but I liked him very much and he made great pots. And he was also a very very fine singer. A colleague of mine – we were talking about him once quite a lot of years ago now – and he said, "Bob Thomas was the nearest thing I heard to Caruso” is what he said, which is rather extraordinary. Anyhow, that was the memory.

How much do you remember about that first production?

The first thing I did here was to understudy Onegin, which was early days for as big a role as that for me, but I got to know that cast who have been friends, those that survive, ever since. So that was memorable and that was a production that I went into rather further down the line with Peter Hall. I remember my first appearance onstage which was as Donald in Billy Budd and I understudied Peter Glossop as Billy Budd. And I can still remember standing on the stage for the first time, as opposed to the London Opera Centre where we did the early rehearsals. Standing on the stage one morning it was dark, and I think we came to a break in the morning’s rehearsal and the lights, the little candles, came on around the theatre and sentimental old me felt a tear gathering in my eyes. And I cried. It was an amazing thing to witness, to see this most beautiful theatre and to be involved in it, not knowing how long that involvement might last.

The first thing I did here was to understudy Onegin, which was early days for as big a role as that for me, but I got to know that cast who have been friends, those that survive, ever since. So that was memorable and that was a production that I went into rather further down the line with Peter Hall. I remember my first appearance onstage which was as Donald in Billy Budd and I understudied Peter Glossop as Billy Budd. And I can still remember standing on the stage for the first time, as opposed to the London Opera Centre where we did the early rehearsals. Standing on the stage one morning it was dark, and I think we came to a break in the morning’s rehearsal and the lights, the little candles, came on around the theatre and sentimental old me felt a tear gathering in my eyes. And I cried. It was an amazing thing to witness, to see this most beautiful theatre and to be involved in it, not knowing how long that involvement might last.

The sense of arrival was palpable.

It was. And surprising too because I had never planned to be involved in opera. I didn’t train to be an opera singer. I had no stage craft at all. I had to pick it up as I went along. I trained to be a singer.

What were the circumstances in which you gravitated towards the other discipline?

Money. I had to make a living.

You studied oratorio and Lieder first.

That was my life at the Royal College [of Music].

Was there an option to study opera?

I could have gone into the opera school. It didn’t have a great reputation at the time and I didn’t see myself doing it until some years down the line. I still towards the end, my last year there, saw myself as being principally a singer of recitals and oratorio as well, and occasionally making it to an opera house. And then I got the opportunity, because a baritone went missing – he took a job and was gone – they needed a baritone and I was the best one going upstairs in the rest of the college. I was approached and said I would do it. It might be good experience. So I did, I went downstairs and did one opera.

Which was what?

It was The Prima Donna by Arthur Benjamin, which I haven’t actually sung since, and nor has anyone else as far as I know.

Below: Sir Thomas Allen as Music Master in Ariadne auf Naxos, 2002 © Bill Cooper/Royal Opera House

However, it must have turned on a light.

However, it must have turned on a light.

Oh, it did. I enjoyed it. I felt an affinity with the stage. I couldn’t do my make-up and I didn’t do my make-up for quite some time - I hadn’t learnt anything of that sort. But the director of it recognised that I had a facility around the stage which was in a very raw state and could be developed and it went on from there.

Had you as a grammar school boy in County Durham already discovered a facility for stage acting?

No. I carried a gun in The Devil’s Disciple. I could march because I was in the church lads’ brigade but speaking verse, rhyming couplets or whatever else – it was usually Shakespeare we did at school – I had nothing to do with. I didn’t get onstage. I rather wish I had.

Not even to sing?

To sing I did.

How good a singer were you as a teenager at, say, 15?

Exceptional.

How good were you before your voice broke?

I was a good boy singer. I was head chorister in the church. But my voice didn't take time to break. I was head chorister at a practice one Thursday night and the following Thursday something happened in that week in between which I didn’t notice but they took the ribbon off me and I went and joined the men in the back row and sang the bass line. I went straight from treble to baritone. And I continued singing through school.

Were you individually tutored?

I was very lucky in several senses. Singing in general then had more street credibility than it seems to have now. We had a school choir and we all enjoyed that. And at the end of the year there would be a school concert, we’d sing choruses from Messiah or The Creation or whatever it might be. There was always the need for a soloist. There was always the recorder group and the school orchestra in which the French master played flute. It wasn't a great orchestra but I played an organ solo, I remember, and also sang a solo. I offered up a song which I sang and it clearly registered. And it was my physics master who played for me – Renaissance man personified – and then offered to give me lessons. I started lessons as a 15-year-old at school.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Comments

...

...