The Secrets of Scott's Hut, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

The Secrets of Scott's Hut, BBC Two

The Secrets of Scott's Hut, BBC Two

Ben Fogle explores the deep-frozen legacy of Captain Scott

Captain Scott's doomed 1910-1913 expedition to the South Pole has become one of the enduring myths of the later British Empire, a paradigm of pluck, grit and a refusal to surrender in the teeth of hideous odds. Subsequently, some historical revisionists have reached a different conclusion, that Scott was in fact an ill-prepared amateur who committed a string of fatal errors.

A new generation of splendid chaps has been revisiting the bitter, haunted wastes once trudged over and sometimes died in by our great explorers. Jasper Rees wrote majestically about James Cracknell's programme The Great White Silence, which was built around the films and photographs shot by Scott's embedded lensman, Herbert Ponting. Now here's Ben Fogle, top chum of Harry and Wills, getting terribly excited about being granted special visitation rights to Scott's hut at Cape Evans in Antarctica, which formed the base camp for the effort to reach the South Pole in 1911.

We might call Fogle a re-revisionist. He admits to having idolised Scott since his childhood, and came not to bury the ill-fated explorer but to thaw him out and present him in fresh, rose-tinted, 360-degree light. To give him his due, Fogle has earned respect in matters of endurance against hostile elements, having rowed across the Atlantic and crossed Antarctica on foot. His cheerful, enthusiastic demeanour suggests that he would find it difficult to think badly of anybody.

Even just watching it on TV, it was obvious that the Cape Evans hut is an extraordinarily complete time capsule, preserving all kinds of data and artefacts about the expedition and the kind of society it came from. Walking through the front door for the first time, Fogle was struck with almost physical force by the layers of compressed history still locked within its wooden walls. He was virtually speechless for the first few moments (Captain Scott in his hut, pictured above).

Even just watching it on TV, it was obvious that the Cape Evans hut is an extraordinarily complete time capsule, preserving all kinds of data and artefacts about the expedition and the kind of society it came from. Walking through the front door for the first time, Fogle was struck with almost physical force by the layers of compressed history still locked within its wooden walls. He was virtually speechless for the first few moments (Captain Scott in his hut, pictured above).

But he quickly recovered, and was soon babbling eagerly about the 10,000 original items which have survived remarkably intact thanks to the freezing temperatures and lack of light inside the building. These range from clothing, reindeer sleeping bags and harnesses for ponies and dogs to foul-smelling cheeses, Heinz baked beans, tinned veal, and copious quantities of biscuits specially made for Scott's trip by Huntley & Palmers. The explorers' clothing was supplied by the likes of Burberry and Jaeger, and was made from natural fibres which were apparently remarkably effective at keeping out the cold (the team had devised what Fogle termed a "willy-hole", a trouserial protuberance through which the wearer could urinate without having his member ravaged by frostbite).

This plethora of famous brand names was all part of Scott's pioneering plan to exploit the then largely untapped goldmine of commercial sponsorship. One of photographer Ponting's major tasks was to make sure Scott's men were pictured in close proximity to well-known commercial products - a large portion of the hut was walled off to serve as Ponting's darkroom - and Scott was well aware of the publicity he could leverage from the burgeoning newspaper industry back home.

This plethora of famous brand names was all part of Scott's pioneering plan to exploit the then largely untapped goldmine of commercial sponsorship. One of photographer Ponting's major tasks was to make sure Scott's men were pictured in close proximity to well-known commercial products - a large portion of the hut was walled off to serve as Ponting's darkroom - and Scott was well aware of the publicity he could leverage from the burgeoning newspaper industry back home.

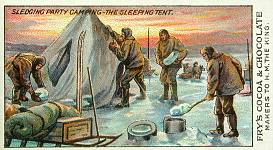

If Scott was forward-thinking or even mercenary in some respects, he was reactionary in others. The rigidly hierarchical structure of the expedition was revealed in the way Scott built walls in the hut to separate the officers and scientists from the "unranked" men, who also had to use their own toilets. Captain Oates was of the opinion that if a fellow "broke down", he shouldn't hesitate to avail himself of a revolver and avoid becoming a burden to his comrades. It still beggars belief that so many sons of the Edwardian era were prepared to submit to months of pitch blackness and temperatures of minus-40 degrees, and would stoically march themselves to death across glaciers through howling blizzards. These were attitudes about to be tested to destruction by the First World War (Scott's team promote Fry's chocolate, pictured below).

Fogle's trip unearthed plenty of fascinating fragments of information, though the programme struggled to fill its 90-minute slot convincingly. As for his efforts to put Scott back on his pedestal, they emitted a whiff of special pleading. We saw Fogle telling a Royal Geographical Society audience that it was time to allow Scott to "be a man... a man with faults, but also with qualities that made other men want to follow him to the end of the earth". But perhaps a better leader could have brought them all back again (Scott's men reach the South Pole, pictured below).

Fogle's trip unearthed plenty of fascinating fragments of information, though the programme struggled to fill its 90-minute slot convincingly. As for his efforts to put Scott back on his pedestal, they emitted a whiff of special pleading. We saw Fogle telling a Royal Geographical Society audience that it was time to allow Scott to "be a man... a man with faults, but also with qualities that made other men want to follow him to the end of the earth". But perhaps a better leader could have brought them all back again (Scott's men reach the South Pole, pictured below).

Particularly unconvincing was his attempt to argue that Scott wasn't merely trying to be the first to reach the South Pole, but was engaged in serious scientific endeavour, as betokened by equipment left in the hut. This conspicuously failed to square with what he'd already told us about Scott's eye for commercial exploitation and his rivalries with both Ernest Shackleton and Roald Amundsen. The latter beat him to the Pole by being better organised and unswervingly focused on that single task.

Particularly unconvincing was his attempt to argue that Scott wasn't merely trying to be the first to reach the South Pole, but was engaged in serious scientific endeavour, as betokened by equipment left in the hut. This conspicuously failed to square with what he'd already told us about Scott's eye for commercial exploitation and his rivalries with both Ernest Shackleton and Roald Amundsen. The latter beat him to the Pole by being better organised and unswervingly focused on that single task.

"This is where the science of climate study began, in Antarctica," Fogle ventured hopefully. Captain Scott as the original crusader against global warming? Under the circumstances, he'd probably have welcomed it.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

Comments

...

...

...

...