Unbound: A Festival of New Works, War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco review - ballet invests in its future | reviews, news & interviews

Unbound: A Festival of New Works, War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco review - ballet invests in its future

Unbound: A Festival of New Works, War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco review - ballet invests in its future

San Francisco Ballet pulls off an unprecedented feat of creativity

You have to hand it to the Americans: they think big. Where the Royal Ballet or ENB might put on three or four new works in the course of a season – because commissions are wildly expensive and a box office risk – San Francisco Ballet has just presented a dozen in the space of two weeks. What’s more, the 12 invited choreographers – four of them Brits or British trained – were given virtually carte blanche to create whatever they liked.

Whatever they liked – really? Presumably carte blanche didn’t mean they were free to present the dancers in the buff, but it did mean the stepsmiths weren’t told whether the work should be abstract or narrative, set to classical music or pop, or whether it should lend itself to being an opener or a closer in a triple bill (which is how the 12 ballets were eventually to be divvied up). The only stipulations were that stage design should be simple and the whole thing fit within half an hour. Given this freedom, it’s remarkable how balanced the four bills turned out to be, thanks, one has to assume, to the curatorial skill of Helgi Tomasson, who has been at the helm of America’s oldest ballet company for 33 years.

Arthur Pita's 'Björk Ballet' is a vivid and deliberate trashing of good taste

The idea of the Unbound festival was “to take the pulse of where ballet is now”, though the absence of certain creative talents (no Wayne McGregor) suggests there's personal taste involved. Tomasson spent the best years of his own starry performing career with George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins in New York, and the athletic neo-classicism they favoured is clearly his ideal.

So where should ballet be heading if it wants to appeal to Millennials? As if 12 new ballets weren’t answer enough the company organised a series of panel discussions to run alongside. Boundless: A Symposium on Ballet’s Future attempted to address some tricky questions, including how to maintain the elements of classicism that distinguish the art form while avoiding what the American scholar Jennifer Homans has called “sickly pieties and terminal athleticism”. Ouch.

If there is a down side to an all-you-can-eat buffet, it’s that the memory of individual dishes becomes blurred. And as this unprecedented feast of new ballet ran its course, the more generic pieces – which is to say those without a standout theme or gimmick – tended to give way to those that grabbed you by the lapels. Which is a little unfair, because some of those quieter pieces, shown in the usual context alongside older repertoire, would have easily held their own.

If there is a down side to an all-you-can-eat buffet, it’s that the memory of individual dishes becomes blurred. And as this unprecedented feast of new ballet ran its course, the more generic pieces – which is to say those without a standout theme or gimmick – tended to give way to those that grabbed you by the lapels. Which is a little unfair, because some of those quieter pieces, shown in the usual context alongside older repertoire, would have easily held their own.

One such was Bespoke (pictured below), by the Australian choreographer Stanton Welch, whose opening four minutes were danced in silence by a lone guy in loose white garb. The combination of Angelo Greco’s beauty of line and perfect feet and the lyrical fluidity of the steps held the packed 3,500-seater opera house rapt in what felt like a little glimpse of heaven. But once the orchestra started chug-chugging its way through a splice of two Bach violin concertos, and dancers en masse joined in to tread a smoothly contoured path through the hinterlands of classicism, it all felt rather too safe.

There was barely more to frighten the horses in Guernica from Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, whose A Streetcar Named Desire was such a touring hit for Scottish Ballet a few years ago. Perhaps the title was at fault, promising more than ballet could deliver. Combative group work, spiky flamenco hands and bullfight imagery only highlighted the limitations of dance in tackling a huge topic such as the terror of war. Guernica the ballet bore barely a quiver of the rage and grief you find in Picasso’s painting.

There was barely more to frighten the horses in Guernica from Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, whose A Streetcar Named Desire was such a touring hit for Scottish Ballet a few years ago. Perhaps the title was at fault, promising more than ballet could deliver. Combative group work, spiky flamenco hands and bullfight imagery only highlighted the limitations of dance in tackling a huge topic such as the terror of war. Guernica the ballet bore barely a quiver of the rage and grief you find in Picasso’s painting.

Perhaps Ochoa should have gone for the narrative option, as did the only other female choreographer in the festival. Cathy Marston’s Snowblind, a drastic concentrate of Edith Wharton’s novella Ethan Frome (a high school text for Americans), was a stunning example of the depth that can be mined from a slender storyline. Reducing the protagonists to three – Ethan, the lonely Massachusetts farmer, Zeena, his sick and mean-spirited wife and Mattie, her lively young cousin and home help – Marston pared the plot to a sliver and relied on Philip Feeney’s orchestral score (incorporating music by Wharton’s contemporary Amy Beach) to create the appropriate bone-chill.

Yet Snowblind never felt small-scale, thanks to Marston’s inspired use of a unisex corps de ballet as whirling snow – not delicate snowflakes as in The Nutcracker, but harsh, murderous, blizzardy sleet, moving in gusts of grey and dirty brown. A pedant might quibble that the ballet failed to deliver the plot twist on which the novel’s classic status depends. But if my own response was anything to go by, it sent its audience hurrying home to devour the book.

Ballet has never been particularly adept at addressing the way we live now, but two of the most successful pieces attempted it. Trey McIntyre’s Your Flesh Shall Be A Great Poem, set to quirky songs by Chris Garneau, sprang from reflections on his grandfather’s dementia. And yet it was full of light and happiness, viewing the end of life as childhood in reverse. The closing solo (pictured, top) for a man stripped to his boxers who found 101 ways to use a bathroom stool was both ingenious and moving.

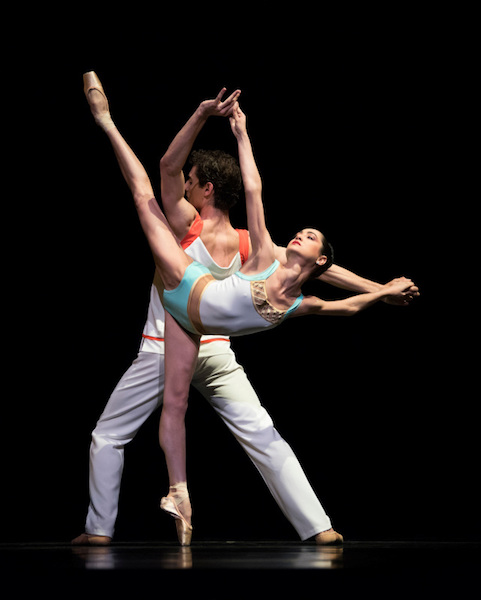

Of all 12, the contribution from Christopher Wheeldon was the most hotly anticipated, for he is not only a choreographer incapable of making a bad ballet, but one of few to have breached the Broadway/opera house divide with notable success. Bound To (pictured above) was a titular twist on the theme of the festival, but less ambiguous, because the object the dancers were "bound to" was their smartphones.

Of all 12, the contribution from Christopher Wheeldon was the most hotly anticipated, for he is not only a choreographer incapable of making a bad ballet, but one of few to have breached the Broadway/opera house divide with notable success. Bound To (pictured above) was a titular twist on the theme of the festival, but less ambiguous, because the object the dancers were "bound to" was their smartphones.

An opening ensemble sees each dancer fixated on a hand-held device, and when they pair off, each continues to peer at the screen over their partner’s shoulder. Just one girl (Dores André) is without a phone, and in a humorous pas de deux she struggles to get Benjamin Freemantle’s attention, resorting to clambering on his thighs and hanging down his back to wrench his gaze from his screen. Wheeldon then abandons the props and turns his attention to all the experiences we’re missing when keeping up with social media. A segment for women in long dove-coloured frocks brings to mind Chekhov’s Three Sisters, dancing against silhouetted winter trees. Do they long to go to Moscow or merely Central Park? Jean-Marc Puissant’s design is gorgeous in its pale grey palette. But it didn’t need the preachy projected captions. We would have got the message anyway: look up and live.

But not one of the works discussed above responded directly to the brief in terms of releasing the art form itself from any perceived shackles (and of course many ballet lovers would prefer it to stay just as it is). Enter Arthur Pita, whose Björk Ballet (pictured below) was a vivid and deliberate trashing of good taste – that is to say elegance, restrained costuming, and all the stuff we'd seen elsewhere in the festival. Set to a string of Björk songs and composed pieces from across her albums, it might have been subtitled The Tacky Horror Show for its Las Vegas-meets-Chinese takeway costumes and settings. At the outset, two dozen tinsel palm trees clatter to the stage fro(m the ceiling, and the next 30 minutes is a non-stop parade of bondage and trashy sci-fi imagery.

There's gender-bending too, natch: guys in yashmaks and women in silver spray paint snogging each other. What larks! The choreography is, shall we say, fit for purpose, ranging from erotic entanglings to bopping on the spot. Several of the soloists are delivered centre stage on a huge bier carried by shuffling slaves. Well why not throw in Carry On Up the Nile as well? If you think liking ballet shouldn't preclude liking a good laugh, then Pita is your man.

There's gender-bending too, natch: guys in yashmaks and women in silver spray paint snogging each other. What larks! The choreography is, shall we say, fit for purpose, ranging from erotic entanglings to bopping on the spot. Several of the soloists are delivered centre stage on a huge bier carried by shuffling slaves. Well why not throw in Carry On Up the Nile as well? If you think liking ballet shouldn't preclude liking a good laugh, then Pita is your man.

But when San Francisco Ballet makes one of its rare visits to London next year, I know which of the Unbound ballets I most want see again: Hurry Up, We're Dreaming, by Justin Peck – another ballet choreographer who has been making waves on Broadway (in the new Carousel). Hurry Up, which takes its title from its upbeat music, an album by Anthony Gonzalez, is a piece that wears its innovations lightly, but it has the feel of classical dance reminted. Shod in white sneakers and clad in silvery jeans and street clothes, the company engage with Peck's choreography with the casual delight of stepping onto new-mown grass at a summer festival. Yet precision abounds, and glorious stretched lines, even in those clumpy trainers: this is a ballet about how it feels to be young. It's how everyone wants to dance, in their dreams.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

R:Evolution, English National Ballet, Sadler's Wells review - a vibrant survey of ballet in four acts

ENB set the bar high with this mixed bill, but they meet its challenges thrillingly

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

Like Water for Chocolate, Royal Ballet review - splendid dancing and sets, but there's too much plot

Christopher Wheeldon's version looks great but is too muddling to connect with fully

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

iD-Reloaded, Cirque Éloize, Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury review - attitude, energy and invention

A riotous blend of urban dance music, hip hop and contemporary circus

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Comments

Thank you for a great review!

Thank you I have found