Putin, Russia and the West, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

Putin, Russia and the West, BBC Two

Putin, Russia and the West, BBC Two

In-depth, authoritative new four-part series ponders the enduring power of Putin

“Who is Mr Putin?” That was the question being bandied about by journalists and Kremlin watchers in the months after Boris Yeltsin’s out-of-the-blue New Year’s Eve 1999 resignation. Vladimir Putin, ex-KGB operative in East Germany, was prominent in the St Petersburg city administration through the early 1990s; called to Moscow in 1996, he held various Kremlin jobs, before being appointed head of the FSB (the KGB’s successor) in July 1998, and in August 1999 Russia’s prime minister.

In 2008 he handed over the presidency to Dmitry Medvedev, becoming again Russian prime minister, while remaining, by general consent, the dominant political figure in the country. Until December 2011, Putin looked all set to resume a new two-term presidency this March that could see him in power until 2024. Popular protests in Russia in December 2011 potentially put that previously shoo-in prediction in doubt, but Putin remains the likely winner of presidential elections this March.

There’s something faintly disingenuous about the remark at the first episode’s very beginning that Yeltsin’s 'eyes fell on' Putin as his successor

Putin, Russia and the West, a new four-part documentary directed by Paul Mitchell, made by production company Brook Lapping for the BBC (and a slate of other international broadcasters as well), examines in detail the changes of those 11-odd years, and is as authoritative as anything we have seen to date. It comes two decades after the same outfit's acclaimed The Second Russian Revolution, and the roster of senior Russian politicos who give up considerable screen interview time must be credited to Russian researcher Masha Slonim, also behind that earlier project. The surprising – to some, at least – events of late last year are obviously beyond its brief.

There’s a division between Putin the man – with various psychological traits that have only grown stronger the longer he has been in power – and Putin the statesman, reflecting and shaping the attitudes of his country. The country he took over from Yeltsin felt itself very much an underdog on the international stage, so from early on Putin’s reassertion of Russia’s world status played to receptive ears at home, even as the international press voiced suspicions from early days.

The first episode “Taking Control” caught the moment media freedom, most notably in television, first came up against the Kremlin – and lost. That was the arrest of media mogul Vladimir Gusinsky, his subsequent exile from Russia, and the transfer of his NTV channel to state-loyal new owners (it was also heavily debt-ridden, which formally forced the transfer). Then the celebrated meeting with the oligarchs, those who had secured control of the great part of Russia’s economy in the 1990s, which set new rules for their relation with the state; somewhat ironic to see an archive interview here with Mikhail Khodorkovsky welcoming such clarification, given that he would go on to push the lines much too far for Putin’s liking, a process that led to his high-profile imprisonment (he remains behind bars today). Putin typically distanced himself from both cases, citing the independence of the prosecutor’s office – but the question hanging over his whole time has been how much any state body in Russia, not least the courts, functions independently of the Kremlin, and whether such diktats come directly from Putin himself.

There’s one surprise at least – ne’er a mention in any of the four programmes of one-time oligarch and Yeltsin era powerbroker Boris Berezovsky, another media magnate whose loss of control of Russia’s main broadcaster was no less significant than Gusinsky’s losing NTV, and who, unlike Gusinsky, did not go gentle into the good night, setting himself up as Putin’s most vociferous foe from exile in the UK. (Russia’s failure to extradite him has left Britain a far from popular international partner for the Kremlin, even while London remains the favourite playground for Russia’s elite, financial and political alike). There’s something faintly disingenuous about the remark at the first episode’s very beginning that Yeltsin’s “eyes fell on” Putin as his successor, when that process was surely driven by Yeltsin’s inner circle, in which Berezovsky was a key player. It leaves us to speculate on a couple of “what if” scenarios: what if Putin and Berezovsky had not fallen into such an acrimonious conflict? And, more far-fetchedly, what if Putin’s predecessor as prime minister, Sergei Stepashin (a far less confrontational character than Putin) had been endorsed for the succession instead?

Condoleeza Rice’s rapport with her Russian counterpart Sergei Ivanov comes across as a genuinely close one: while 9/11 brought American alerts up to the highest level, Ivanov reassured her that Russian alerts were being decreased proportionately, leaving Rice thinking that “the Cold War was really over”. Despite that, ongoing negotiations over nuclear weapons treaties, as the USA left behind the ABM treaty to set up a new missile defence shield, proved distinctly problematic (deep Russian hostilities to proposed US warning bases in Poland and the Czech Republic were only pacified by a subsequent climbdown by Barack Obama).

Putin, Russia and the West goes beyond its brief, effectively capturing most of the dramatic moments of the era

The big hiccoughs came in relation to Russia’s “near abroad”, Ukraine (which takes up much of episode two, “Democracy Threatens”, next week) and Georgia (covered in practically all of episode three, “War”), not least because both were at different times up for NATO membership (strongly favoured by the US). Ukraine’s 2004 elections saw a first-round victory for Viktor Yanukovich, the candidate both of the old Kiev regime and of Putin’s Kremlin, before that was overturned in the country’s Orange Revolution: Putin had sent in his Kremlin spin-doctors to work on that one, and his premature message of congratulation to Yanukovich certainly left him with egg on his face (definitely not his favourite state, even if more officially it was expressed that Russia had “lost prestige”). The eventual winner, Viktor Yushchenko, made his first trip abroad as president to Moscow, and a meeting with Putin; given that Yushchenko had been severely poisoned, his face badly disfigured, in that campaign, his remark, “his [Putin’s] behaviour had caused a lot of bitterness” must rank among diplomacy’s greater understatements.

The preamble to Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 set the sides even more into opposition, with the US and Russia never so close to war. Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili, who had overthrown Soviet veteran Eduard Shevardnadze, was pursuing a strongly pro-NATO and Europe line, and ranked as Putin’s enemy number one. The redoubtable Condoleeza Rice admits to some surprise when, on one of her negotiating trips to Moscow around that time, she was brought along to a Moscow dacha where Putin and entourage were celebrating a colleague’s birthday. Formal discussions continued later in an adjoining room: such is personality-led diplomacy. The conflict over Georgia was the only real moment when the driving force for negotiation came from Europe, in the shape of Nicolas Sarkozy.

The title of the series’ fourth and last episode, “New Start”, may have assumed a new relevance given the events of the last two months in Russia, but in the programme’s context it refers to the attempt by the incoming Obama administration to “reset” relations with Russia. As diplomatic gestures go, Hillary Clinton presenting her Russian colleague Sergei Lavrov with a button marked with that word in English, but with its Russian equivalent mistranslated as “overcharge”, must rank among the more embarrassing. Though Obama was positively received by Medvedev, it duly took a one-to-one phone conversation between them to clear up another deadlock on more nuclear reduction talks that had stalled in more traditional negotiating forums.

What of the future? There’s a revealing comment from Michael McFaul, Washington’s brand new ambassador to Moscow, that Putin has “one foot in an antagonistic mindset”, with his refrain, “You can’t treat Russia like that.” Clearly that was an approach that won him real popularity at home in his time as president, and the fact that he often expressed his views in rather fruity vernacular terms made little difference with domestic audiences, while periodically unsettling his international partners. Whether Russian voters are ready for an indefinite continuation of that style, accompanied by ever-increasing corruption, and a series of TV reports showing Putin in one macho pose after another, will be among the open questions of this year.

Putin, Russia and the West goes beyond its brief, effectively capturing most of the dramatic moments of the era. If it leaves one direction little explored it’s in the variety of opinions to be found in that most nebulous of terms, “the West”. One of the achievements of Putin’s foreign policy was to divide Europe, often around issues like energy. There’s no top-level voice from France to be found here, while Putin’s close friendship with Silvio Berlusconi, which assumed in its final years something of a pantomime character, isn’t alluded to at all. The top German voice is ex-Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who departed – ignominiously in the view of many of his former colleagues - from leading his country straight into a lucrative consultancy with a Russian energy pipeline under the Baltic sea.

Putin, Russia and the West goes beyond its brief, effectively capturing most of the dramatic moments of the era. If it leaves one direction little explored it’s in the variety of opinions to be found in that most nebulous of terms, “the West”. One of the achievements of Putin’s foreign policy was to divide Europe, often around issues like energy. There’s no top-level voice from France to be found here, while Putin’s close friendship with Silvio Berlusconi, which assumed in its final years something of a pantomime character, isn’t alluded to at all. The top German voice is ex-Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who departed – ignominiously in the view of many of his former colleagues - from leading his country straight into a lucrative consultancy with a Russian energy pipeline under the Baltic sea.

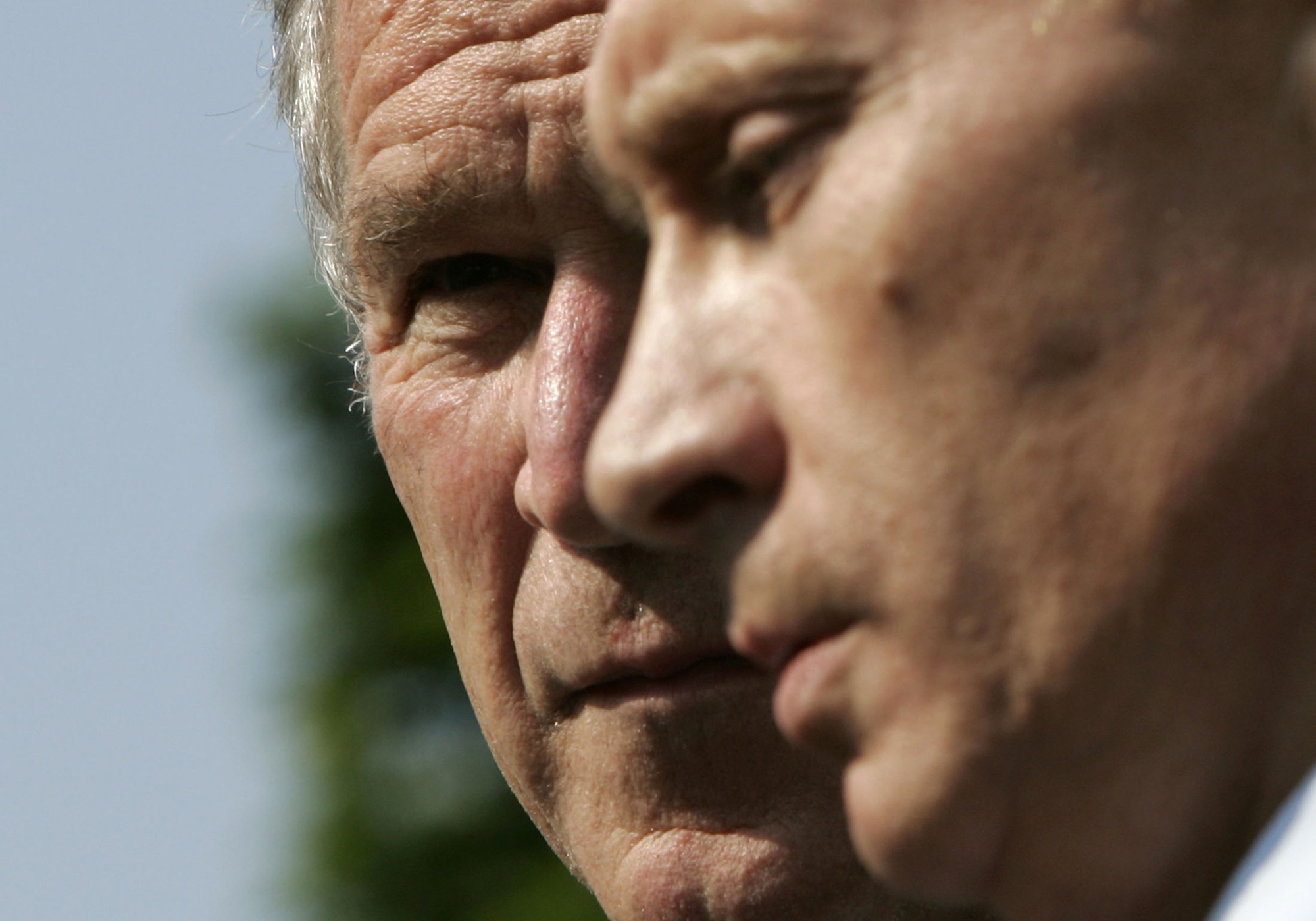

Britain gets no more of a look-in than Poland, with David Milliband left with a few minutes at the end of episode two to comment on the polonium poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko (pictured above left) in London in November 2006. But he speaks powerfully of a reversion to the worst habits of the Cold War, and wonders whether Russia is capable of occupying an “honourable place in the international community of nations”. For all the diplomatic comings-and-goings of the decade, the treaties negotiated, the conflicts averted, it’s surely the likes of Litvinenko’s murder – or the assassination in Moscow a month earlier of the crusading Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, with subsequent protests on a popular level around the world – that will stay in our minds.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Comments

hi there, i watched some of

This is easily the best