Katya Kabanova, English National Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Katya Kabanova, English National Opera

Katya Kabanova, English National Opera

Janacek's battle between darkness and light sharply rendered in a stark new production

It's amazing how much you can tell of what lies ahead from the way a conductor handles a master composer's first chord. Katya Kabanova's opening sigh of muted violas and cellos underpinned by double basses should tell us that the Volga into which the self-persecuted heroine will eventually throw herself is a river, real or metaphorical, of infinite breadth and depth.

David Alden's production and a strong cast eventually match their conductor's demands in a third act which ruthlessly enfolds Katya's struggle towards the light in terrifying darkness.

The insights, though never the pace, are slow in coming. In telescoping Russian theatrical pioneer Ostrovsky's 1859 drama of stifling, brutish provincial life, Janáček sheds nuance in most of the characters around the loving, tortured wife of mother's boy Tikhon Kabanov. They are one-dimensional, but they should still be recognisable as human beings, which not all of them are here.

Alden's favourite brand of expressionism, last season stretching the already broader-brushstroked Borough folk of Britten's Peter Grimes on the rack, fostered over-acting in John Graham Hall's Tikhon, Clive Bayley's too-repulsive uncle Dikoy and several of the smaller roles. Anna Grevelius and Alfie Boe as spirited, socially aware young lovers Varvara and Kudriash were more successful in embodying caged, superabundant vitality. Their projection of the text was impeccable, too, a virtue of the evening as a whole much assisted by Alden's insistence on downstage delivery.

Against these bundles of energy, the stillness of Susan Bickley's very imperial Kabanicha, her awful authority emphasised by gleaming tone rather than the usual paintstripping old-baggery, is matched by the pent-up feelings of Patricia Racette's downtrodden daughter-in-law. This Katya may not attain the ultimate in sensual abandon, which would be difficult given lyric-heroic tenor Stuart Skelton's hardly charismatic object of desire. In any case Janáček makes sure the sensuousness is always shipwrecked by self-flagellating religious guilt. What Racette does have in spades is a gleaming, secure middle register which allows her to enunciate beautifully and which connects well to a slightly more spread top.

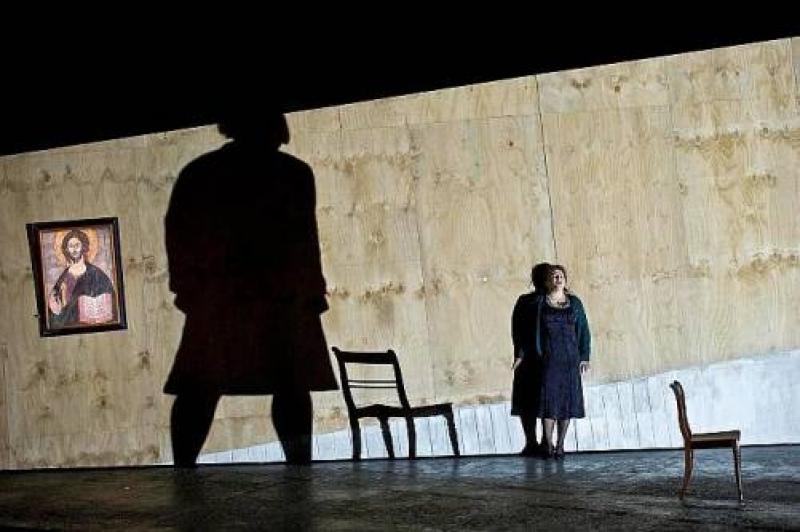

The real pay-off comes in the insistence on the space between Katya and everyone else. On the ENO's wide stage, extended beyond the proscenium arch to which Racette's heroine clings for comfort, distance is always emphasised, whether in the bare open vasts in front of the white slashes on canvas Charles Edwards uses to suggest the Volga, or in the shadows that wedge themselves between the characters against the wall of the Kabanov house. Perhaps the garden love-scene is too bleak, symbolic though it may be of Katya's still riven state of mind. Under a single lamp-post, the men never take their coats off; can this really be a summer night?

Shocking rewards are more justifiably reaped in the starkest of third acts. It hits us all the more powerfully without a preceding intermission (Glyndebourne undermined the supreme tension of Nikolaus Lehnhoff's unsurpassable Katya with a dinner interval three times the length of what followed). The half-ruined church with frescoed scenes of hell in which characters seek shelter from the impending storm becomes a proto-revolutionary poster shrilling damnation which collapses, like the heroine, at the height of the onslaught. Everything closes down for Katya's endgame, even the abstract river vista which will be her only possible way out. Alden's finest touch, hand in glove with Adam Silverman's quick-change lighting, finds Katya and Boris walking a tightrope in near-darkness from opposite sides of the stage to meet for one brief moment of true togetherness.

The hushed tenderness of the ENO Orchestra's phrasing under Wigglesworth is almost too painful to bear here. Either side of it a single clarinet note seems to come from the depths of Katya's tormented spirit and an oboe wails an unearthly threnody over her drowned body. Janáček, who insisted upon the expressive significance of every tone from voices and instruments, would surely have approved. And like Robin Ticciati, conductor of the superlative Glyndebourne on Tour Jenůfa, Wigglesworth understands the unbearable tension of silence. What is unsung or unplayed is as vital as what we see. When Alden's pared-down, even in earlier stages uncharacteristically bland vision matches that, great music-theatre happens naturally.

- Katya Kabanova is at English National Opera, London Coliseum until 27 March

- Check out what's on in the ENO season

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Káťa Kabanová, Glyndebourne review - emotional concentration in a salle modulable

Janáček superbly done through or in spite of the symbolism

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Buxton International Festival 2025 review - a lavish offering of smaller-scale work

Allison Cook stands out in a fascinating integrated double bill of Bernstein and Poulenc

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Tosca, Clonter Opera review - beauty and integrity in miniature

Happy surprises and a convincing interpretation of Puccini for today

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Hamlet, Buxton International Festival review - how to re-imagine re-imagined Shakespeare

Music comes first in very 19th century, very Romantic, very French operatic creation

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Falstaff, Glyndebourne review - knockabout and nostalgia in postwar Windsor

A fat knight to remember, and snappy stagecraft, overcome some tedious waits

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Salome, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - a partnership in a million

Asmik Grigorian is vocal perfection in league with a great conductor and orchestra

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Semele, Royal Opera review - unholy smoke

Style comes and goes in a justifiably dark treatment of Handelian myth

Comments

...

...