Anna Maxwell Martin: 'I like playing baddies' - interview | reviews, news & interviews

Anna Maxwell Martin: 'I like playing baddies' - interview

Anna Maxwell Martin: 'I like playing baddies' - interview

She's been Sally Bowles, Lady Macbeth and Elizabeth Darcy. Now for a gritty courtroom drama about rape

She was Lyra in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials at the National, she has shared the stage with Eileen Atkins (in Honour and The Female of the Species), played Isabella in Measure for Measure, Regan in King Lear and Sally Bowles in Cabaret.

Maxwell Martin has scarcely been out of work since her first job after graduation, in The Little Foxes at the Donmar. Now she is back at the National Theatre, in Consent, a new play by Nina Raine, directed by her husband Roger Michell, who previously directed Raine’s lauded Tribes at the Royal Court. Maxwell Martin’s character, Kitty, is married to Edward (played by Ben Chaplin, fresh from Apple Tree Yard), a barrister who finds himself on the opposite side to a friend and fellow barrister in a rape case. Public and private matters intertwine painfully as Raine takes a forensic view of what exactly constitutes the truth, how legal procedures can twist everyday language and experience. The dialogue is well-observed, sharp and funny. Born in 1977 in Bewdley, Yorkshire, to scientific parents – her father was managing director of a pharmaceutical company, her mother a researcher – Maxwell Martin read history at Liverpool University before attending the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. She has two primary school-age daughters with Michell.

Born in 1977 in Bewdley, Yorkshire, to scientific parents – her father was managing director of a pharmaceutical company, her mother a researcher – Maxwell Martin read history at Liverpool University before attending the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. She has two primary school-age daughters with Michell.

Soon she will be seen in a new BBC comedy series about parenting, Motherland, by Graham Linehan, Sharon Horgan, Helen Linehan and Holly Walsh, but for the moment she is new mother and troubled wife Kitty in Consent. In a break from rehearsals to talk to theartsdesk, she comes over as relaxed, fun and refreshingly down to earth.

HEATHER NEILL What is it like being directed by your husband?

If you fluff a line you feel like a right tool in this play

ANNA MAXWELL MARTIN: Roger is a brilliant director, very ordered, very together. He delivers you very safely to the preview stage. He’d already cast a lot of the parts before he offered me mine and I knew quite a lot of those actors and knew they were brilliant and good people to work with, so I said yes. Working with him has often been a disaster before because he finds it difficult that I muck around a lot, I’m quite giggly. He’s the boss – and it is annoying, I can see that – but it’s my way into working, giggling and having fun and he finds that quite difficult. I don’t release a character by batting my head against a brick wall in the wings. But this one’s been really easy. I suppose we’ve been together a long time – over a decade – and perhaps he trusts me more, I don’t know.

Is it hard to switch off after work?

We have a rule: we don’t talk about it at home. It wouldn’t be fair on anyone else in the cast. We just don’t say anything; even the tiniest thing could escalate into a conversation about all sorts of things. I think he worries that I’m going to be inappropriate; I haven’t got a very good filter on my gob! I think he worries about that. I’m a company member, the same as any other company member.

The subject of the play, the treatment of rape in law, is potentially controversial. How have you researched it?

Heather [Craney], who plays Gayle [the victim in the rape case], has talked to Rape Crisis. There’s been group research too: we went to court a couple of times, we’ve spoken to three or four barristers who’ve come into the room. Of course, I’m not playing a barrister; Kitty is in publishing and I know people in publishing, so it’s no great stretch for me.

What have rehearsals been like?

It’s a really good play and it’s revealed itself to be even better in rehearsal. If you fluff a line you feel like a right tool in this play. You really have to keep it motoring, keep the arguments really strong, really together, really quick. It’s intensely written but funny. Roger is a very collaborative person and Nina is very supportive and easy to collaborate with, so it has been a help having the writer in the room all the time.

Is it a concern that some women might be put off by the play from reporting a rape?

That’s a really tricky thing, but it’s a play, not real life, and therefore it shouldn’t necessarily come with a warning. It’s not a universal message and it is very specifically about these people. Everyone knows the stats – that very few rape prosecutions end in a positive outcome – and there’s no point in the play lying about that. We can’t change the situation; that’s for others to do. It’s because of the nature of rape: it’s one person’s word against another’s. There are no witnesses.

Do you need to like the character you are playing, or at least see her point of view?

No. I like playing baddies. I don’t need to like the character I’m playing and I also don’t need people to feel sympathy for them. I don’t need to see things from Kitty’s point of view. I’m not at all like her, but I’ve got to make her seem believable. There’s light and shade in all the characters in this play – good and bad in all of them.

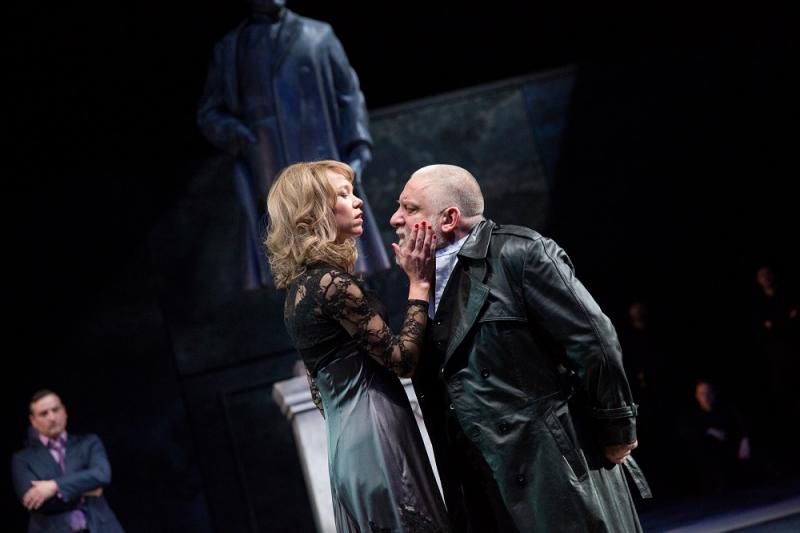

If you are playing someone like Lady Macbeth, you don’t find it hard to leave the character behind? (Pictured below: Anna Maxwell Martin with John Heffernan in Macbeth. Photograph by Richard Hubert Smith) I don’t get overwrought. My biggest challenge in playing Lady Macbeth [at the Young Vic in 2015] was that I had to come on and be on my own onstage – reading a letter aloud. So embarrassing! Mortifying! Please give me someone to talk to! I could never do a one-woman show. One of my dearest friends, Eileen Atkins, does a one-woman show [as Ellen Terry] and she’s unbelievably brilliant in it. I could never do that.

I don’t get overwrought. My biggest challenge in playing Lady Macbeth [at the Young Vic in 2015] was that I had to come on and be on my own onstage – reading a letter aloud. So embarrassing! Mortifying! Please give me someone to talk to! I could never do a one-woman show. One of my dearest friends, Eileen Atkins, does a one-woman show [as Ellen Terry] and she’s unbelievably brilliant in it. I could never do that.

In the past you have criticised roles available to women as dumbed down. Is that still the case?

Things are really changing quite quickly in that respect and in terms of diversity. It took a long time to get going, but people are mindful of that, are talking about it. Also you have this world opening up where Glenda Jackson plays King Lear. I’ve played loads of good characters on film and stage, so I wouldn’t necessarily moan about it – although there aren’t enough to go round, for sure.

You began performing as a singer, didn’t you? Would you like to do more?

I did do lots of singing when I was younger. I’d love to do more – not musicals, though: I was not very good in Cabaret. I’m constantly apologising to Rufus [Norris, who directed] for it! Maybe I just wasn’t confident enough. I wouldn’t feel so neurotic about it now. I’d love to be a folk singer – have a second career!

Did you have any heroes in the business when you were growing up?

I always wanted to be Julie Walters. Actually I always wanted to be Julie Walters in Victoria [Wood]’s stuff.

You were very young when you played Lyra, only a couple of years after you graduated. That must have been challenging.

It didn’t feel like that at the time. It sounds arrogant to say so, but I didn’t feel daunted by that play, I think because I wanted to play the part so much. I loved the books, had huge respect for Philip [Pullman], and Nick [Hytner] planned for it really well, knew what he wanted and was a strong force in the room. I never felt that I was floundering because I could focus totally on the part and loved playing it and found it easy. There’s no point in getting in a massive fandango about it if you love playing the part.

It didn’t feel like that at the time. It sounds arrogant to say so, but I didn’t feel daunted by that play, I think because I wanted to play the part so much. I loved the books, had huge respect for Philip [Pullman], and Nick [Hytner] planned for it really well, knew what he wanted and was a strong force in the room. I never felt that I was floundering because I could focus totally on the part and loved playing it and found it easy. There’s no point in getting in a massive fandango about it if you love playing the part.

And Esther Summerson, in Bleak House, came soon after (pictured above).

Again, it wasn’t that daunting because I loved the part so much. And all the collaborators on that were extraordinary, Andrew Davies’s script was brilliant and it was so well cast. Those jobs are easy.

Have there been any that weren’t?

I’ve had jobs which were a nightmare because people weren’t working hard enough or you weren’t well enough prepared. You are juggling so many things – the relationships in the room – and we all behave badly at times. Occasionally, the job can be stressful because you are walking on eggshells – it’s an artistic endeavour. But look, I’m really lucky, I love my job and I have hardly ever had any bad experiences or worked with people who were difficult.

I don’t get in a terrible state. I don’t over-think acting – it doesn’t help. You need to be prepared, to know what world you come from (exactly as Roger has done for the guys who are playing barristers), but I don’t over-think lines, I just try to think what I’m doing to the other person.

What is your character in Motherland like? You have said – despite being smiley in real life – you find that hard when acting.

I don’t smile in Motherland. I’m a nutter! It’s really well written and the pilot was really funny. I’ve not done that much comedy and on the first day I was terrified. I had to ad lib on my own, shouting out of the car window and I was nearly in tears. I did have a semi nervous breakdown on the first day – I was supposed to be having a nervous breakdown - but by the third day I got into it and I have really loved doing it.

And what about Hollywood?

No.

Any parts you’d like to do?

I’d love to have a go at Beatrice. I’d like to do A Doll’s House. But new writing can be exciting if it’s as good as Nina’s.

This is your sixth time at the National Theatre. What is its allure?

Yes – the Stoppard trilogy, Honour, Three Sisters, Dark Materials, then King Lear (pictured above, Anna Maxwell Martin with Simon Russell Beale), then this. The National has amazing people working for it. It used to feel a bit ramshackle – and there’s a sweetness to that. The operation started to get a lot slicker with Nick [Hytner] and you get this little folder of information now when you arrive. You used to wander around in a daze. But it hasn’t changed that much. I met my husband here, in Honour, in the same theatre, then the Cottesloe. It’s nice to be back with my husband/director!

- Consent, a co-production with Out of Joint, is at the Dorfman Theatre until 17 May

- More interviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Where is this comment heading