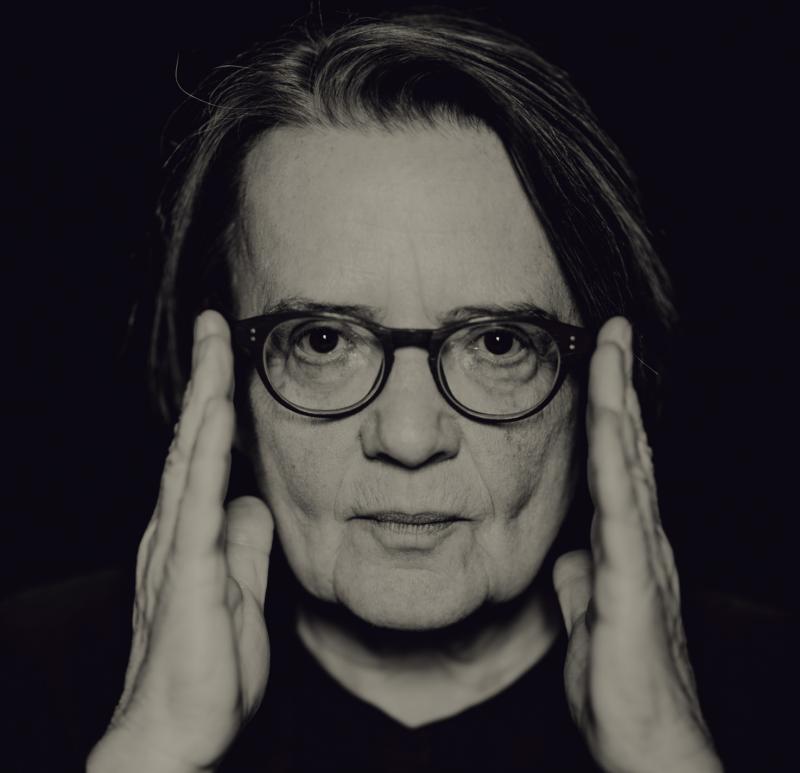

Filmmaker Agnieszka Holland: 'Without journalism, democracy will not survive' | reviews, news & interviews

Filmmaker Agnieszka Holland: 'Without journalism, democracy will not survive'

Filmmaker Agnieszka Holland: 'Without journalism, democracy will not survive'

'Mr Jones' director discusses why she's fascinated by Europe's darkest hours

Agnieszka Holland is one of Europe's leading filmmakers. Growing up in Poland under Soviet rule, her films have often tackled the continent's complex history, including the Academy Award-nominated Europa, Europa, In Darkness and Angry Harvest. In America, she's become a trusted hand for prestige television, with credits on The Wire, House of Cards and The Killing. Her latest film, Mr.

OWEN RICHARDS: What first drew you to this story?

AGNIESZKA HOLLAND: The script was sent to me by the writer Andrea Chalupa. She’s an American journalist of Ukrainian descent, and her grandfather was one of the survivors so she’s very sensitive to the story. Also as a journalist, she became extremely inspired and intrigued by Gareth Jones’s story. So she put it together, adding George Orwell, who was also connected to her grandfather’s story, and she sent it to me.

I was reading quite a lot of scripts about the atrocities of 20th century because I did three holocaust movies. Most of them I was putting on the side because it was getting too much. But I read this one and I found it very relevant. The communist crimes are not known enough, they’ve been forgotten and forgiven which I think is very wrong, not only for the moral reason but also because of the consequences for the future. I became really aware of that when I read a survey in Russia about who was the most important leader of Russian history, and Joseph Stalin came first. I imagined immediately what we would say if a similar survey was made in Germany and Adolf Hitler came at the top. It means a lot of people are watching the past in a very wrong way and it means the lessons have not been learned. Those nameless victims are crying for recognition somehow.

Gareth Jones’s story is known to historians but wasn’t known to the people of Wales. I thought it would be great to celebrate his courage, and show his model for contemporary journalism. There are many journalists now who are taking risks to investigate and report the truth, sometimes for a very high price.

Also, what was very interesting to me was the relevance of the story against production of fake news, using propaganda as an important political tool to serve populist agendas, and the ease with which it’s going on. Do you think it’s the role of cinema to remind people of history and the truth?

Do you think it’s the role of cinema to remind people of history and the truth?

I don’t know if it’s cinema’s role altogether. It’s first role is entertainment. But, for me personally, with my temperament and life experience, my vision of the present and the future, I feel the responsibility not only as an artist but as a citizen of the world, and Europe, and Poland, to become a kind of signalist. For me it’s something that is important, but I don’t want to say that all filmmakers are obliged to make political statements.

But what was important to me was to make this kind of movie, not as a political statement, but to show the complexity of history. Show the different reasons why we come to the place of no return, where disaster is inevitable.

Also, I was always attracted to the mystery of the “good”. How it happened in the war people could be so lazy, or so mean even. So easily they are receiving this message they can be evil and kill other people, and decide who is worthy of living and who is not. Then, how it happens that some people go against the flow, and choose justice and empathy as their main behaviour, and we don’t know why. Is it some gene? A gene of justice? I don’t know, but because it is a mystery, it is interesting to watch and show those people.

As you said, you’ve done a lot films set in World War Two and under the Soviet Union, have you got any closer to finding an answer to what makes people choose justice?

No! Not closer, but I believe more and more are real. You are always suspicious of people’s intentions, maybe they want to show that they are better than others. Altruism is always this other side, but some people just have this imperative.

And with Gareth Jones, we know very little about this man, how he really was. I think at the start, it’s curiosity and ambition that he will find a story, and he will be the first to report it. Just like he was the first person to interview Hitler after his rise to power. Then, after he’s seen what he’s seen, the impact and the scale of this tragedy and disaster, he became the messenger for those people, because he didn’t have a choice. As an honest man, he had to stick to the role of the messenger, no matter what it meant for his future.

Do you think there are lessons to be learned from his approach to journalism for the modern day?

Listen, I think we are in this situation where societies are polarised and divided, countries are divided, nations are divided. The press, media and television are mostly following this division. The media is serving one side, depending on which political agenda they follow. It’s truly dangerous. It means the division is only growing, and you don’t know how to recognise facts from fake news. With social media and the internet, it’s become even more dangerous, and easier to manipulate.

The honest, objective journalist who speaks to the truth of the facts, and doesn’t serve any agenda. Even if the journalist has opinions and believes one is better than the other, they have to report the truth. Without this journalism, democracy will not survive. Fake news is the biggest danger to democracy.

How aware were you of the Holodomor before this project?

I was a little bit aware because I was living in a communist country when I was about 15 and I started to really understand how bad it is, how many lies and crimes were happening. I started to study it, but the material I was able to read wasn’t officially available, but we had some important immigration publications.

It was impossible to legally read George Orwell’s novels. It was printed outside of Poland and smuggled in. It’s why I had such an interest in it because it was like forbidden fruit, it seemed more interesting than it would for a young Englishman. So pretty soon I heard about the big famine. I didn’t know the impact of it, and actually the first time I read a bit more about it was like 10 years ago in Timothy Snyder’s book Bloodlands. He’s one of the most important historians of this area and time, and it was the first time I read about Gareth Jones. I love the aesthetics of the film and how they differ between countries. What was your approach to capturing this time period?

I love the aesthetics of the film and how they differ between countries. What was your approach to capturing this time period?

For the character Gareth, going to these places was like going to a different world, even if it’s within the same country. The life in Moscow, especially the life of the international correspondents and the high-class officials compared to the poor people in Moscow, was like black and white. But then the lives of the poor in Moscow and the dead in Ukraine is incredibly different again. So we had to express this visually, the difference between the destinies and the situation in both places.

Also, I was using some stylistic tools inspired by the Russian Soviet avant-garde because the country was having this energy of the culture, and at the same time producing the most incredible crimes against humanity. Some people even knew about the bad things going on, like Walter Duranty says in the film, “You can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs.” Many people at this time believed that even if the costs were terrifying, it was worth it for the bright future.

It looked like a very cold and brutal conditions when you were filming in Ukraine, how difficult was it?

We didn’t plan it! We shot at the beginning of March, exactly the days when Gareth Jones would’ve visited Ukraine, just by chance. We were told that due to global warming, normally in the Ukraine the temperature would be very mild and there’s no snow at all. Me and my cinematographer came up with some visual concepts of the yellowish brown grasses and patches of snow, and when we arrived, the snow was so high I was unable to walk! James Norton our lead actor managed, but somebody had to walk in front of me to clear the way. We had days of -20°C on the first shooting week, and James arrived straight from London, so for him it really was a journey to a different world, which helped I think.

There’s been some controversy from members of Gareth Jones’s family over the inclusion of cannibalism in the film. This did happen during the Holodomor, but there’s no evidence Jones took part. What was the reason for including this in the film?

Cannibalism was pretty far spread. Any countries where you have famine, cannibalism comes second after you eat all the animals and roots, then you eat the dead’s flesh. There were tragic situations where dying mothers would beg their children to eat them. That is something that is shameful to speak about, but without talking about it we don’t understand that this crime was not only against people’s bodies, but their souls.

In the scene where Gareth takes part in this without knowing, we felt this was necessary. We cannot make him somebody who is just watching other people do this. He has to experience it and then the audience can really identify with the tragedy of the people through him. He is our medium. I don’t think it makes him worse or guilty.

I’m sorry about this controversy with a member of Gareth’s family who didn’t like this approach. The nature of this film is not a documentary or Gareth Jones’s biography, it is the story of courageous men who reported the truth about the tragedy of millions, and his courage is the main truth about him.

What would be the one message you want people to take away from this film?

I want to say that we have been not indifferent. When we see or feel that something is really wrong going on around us, we have to speak out. When the three conditions come together, the corruption of the media, the cowardice and conformism of government, and the indifference of society, anything can happen.

- The BBC Storyville film Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones screens at Regent Street Cinema, London on Thursday February 6 at 18.30

- Mr Jones is released in cinemas on Friday February 7

- Read more film interviews and reviews on theartsdesk

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Little Trouble Girls review - masterful debut breathes new life into a girl's sexual awakening

Urska Dukic's study of a confused Catholic teenager is exquisitely realised

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Young Mothers review - the Dardennes explore teenage motherhood in compelling drama

Life after birth: five young mothers in Liège struggle to provide for their babies

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Blu-ray: Finis Terrae

Bleak but compelling semi-documentary, filmed on location in Brittany

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Sex review - sexual identity slips, hurts and heals

A quietly visionary series concludes with two chimney sweeps' awkward sexual liberation

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Sorry, Baby review - the healing power of friendship in the aftermath of sexual assault

Eva Victor writes, directs and stars in their endearing debut feature

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Blu-ray: Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Fast-paced and visually inventive Czech comedy

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Oslo Stories Trilogy: Love review - freed love

Gay cruising offers straight female lessons in a heady ode to urban connection

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Beating Hearts review - kiss kiss, slam slam

Romance and clobberings in a so-so French melodrama

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

Materialists review - a misfiring romcom or an undercooked satire?

Writer-director Celine Song's latest can't decide what kind of film it is

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Leonie Benesch on playing an overburdened nurse in the Swiss drama 'Late Shift'

The Guildhall-trained German star talks about the enormous pressures placed on nurses and her admiration for British films and TV

Comments

Her father helped establish

This is an interesting