After all the encomia for Natalia Osipova it’s time for a paean to another Bolshoi ballerina, whose witty underplaying and conquest of style makes her the lady I’d choose to see shipwrecked in full tutu, diamonds and pink satin pointe shoes on any desert island I fetched up on. Maria Alexandrova starred in two 19th-century restorations of palatial opulence - the pirate party Le Corsaire and the princess party Paquita. Mistress of balletic patisserie, she decorates these glorious old wedding cakes of choreography with delectable sugar rosettes in her footwork, leaps of lightest meringue, and a hint of citrus in her dimpled smile.

This is the kind of epicurean artistry that is rarely seen in young ballet dancers who all want to show all that they can do, rather than conceal all that they can do. It was what spoiled the dancing of other ladies, such as the second lead of Le Corsaire last night, Marianna Ryzhkina, who fails to command with her arms and back the perfect spatial architecture that Alexandrova (pictured right by Sergey Gavrilov) proudly outlines and then tosses away with a sophisticated flick of her hands. Golly, but Alexandrova’s good.

In both Le Corsaire and Paquita, we had the luck to see her partnered with the fruity Nikolai Tsiskaridze, who is an entire floor-show in his kit and make-up alone. As a pirate who kidnaps his pirate moll back from a seraglio, he wears long ringletted hair that he can toss about dramatically, a drop earring (ditto), and fetching George Clooney stubble; as a nobleman who marries a gipsy girl who turns out to be a princess, he sports a long ponytail, sideburns that reach the corners of his mouth, and moustaches that reach almost to his ears. In both rigs, he smiles broadly like a goal-scorer whenever he catches the audience’s eye, which is basically as often as possible.

In both Le Corsaire and Paquita, we had the luck to see her partnered with the fruity Nikolai Tsiskaridze, who is an entire floor-show in his kit and make-up alone. As a pirate who kidnaps his pirate moll back from a seraglio, he wears long ringletted hair that he can toss about dramatically, a drop earring (ditto), and fetching George Clooney stubble; as a nobleman who marries a gipsy girl who turns out to be a princess, he sports a long ponytail, sideburns that reach the corners of his mouth, and moustaches that reach almost to his ears. In both rigs, he smiles broadly like a goal-scorer whenever he catches the audience’s eye, which is basically as often as possible.

He is much stouter now than he was, but still has those uncannily split legs in his jumps, and partners like the buttress of a cathedral. To total astonishment in the hall last night, he performed a remarkable Corsaire pas de deux (the one Nureyev immortally did with bare chest but here Tsiskaridze wears skirt and trousers, boots, waistcoat, little cap, sash and what looks like a man-bag), pulling off a tricky series of spinning jumps with enormous aplomb and grinning at the storm of applause. That’s entertainment.

Though it’s not class, which is what Alexandrova has in spades. In Paquita she has to trump a catwalk of exhibitionist ballerinas - who in Friday’s cast included the sensational Osipova, the elegant Maria Allash and the neat Nina Kaptsova - and gave a masterclass in regal understatement. In Le Corsaire she has to drive a story of utmost silliness, emitting emotions from joy to wretchedness, all the while with the complicity of a glance that draws spectactors in alongside her to enjoy the nonsense.

Petipa is credited with the choreography for both, and both are restored close to his final 1881 and 1899 productions by Yuri Burlaka, Le Corsaire with added choreography by Alexei Ratmansky too. Both productions have a luscious unhurriedness that is all of a piece with the stately pageantry of the landmark Mariinsky restoration of The Sleeping Beauty. In other words, though they aren’t on the same level as dance entertainment (Le Corsaire is really a pantomime with dance numbers attached), they do feel as if they all come from a particular context of theatrical style and society. This is a great and relishable merit, and it’s fine to see what a true Bolshoi stylist like Alexandrova makes of this time-warp - she rises above her competition in the Paquita parade by wrapping herself smilingly in mystique, not showing all her technical armoury at once, but choosing how to let us glimpse it.

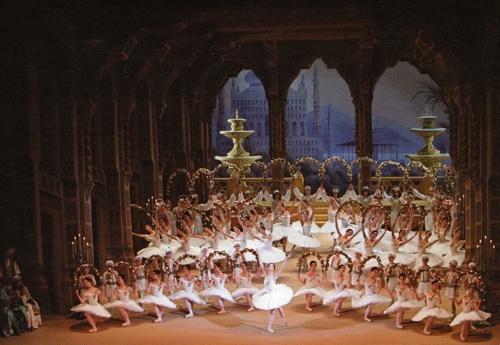

Sets and costumes for both ballets are mouthwatering - a wreathed garden palace of Spanish rococo in Paquita, populated by dancers in a rich, restrained palette of garnet, black and vanilla, while Le Corsaire offers a picturesque Mediterranean port (pictured below), a superb seraglio, a magnificent pirate grotto and a general attention to what will give the audience something to gawp at. The Act Three "Jardin Animé" scene is saturated in girlishness of utmost fragrance, glistening white tutus accessorised with flowers, fans, tiaras, veils and (rather erotically) the odd pistol or two.

Musically Paquita wins hands-down, Minkus being much more Petipa’s soulmate in vigorous waltz tunes than the hotchpotch of the Le Corsaire music, said to be by Adolphe Adam (of Giselle), but whispered to have quite a handful of duff hands concerned.

Musically Paquita wins hands-down, Minkus being much more Petipa’s soulmate in vigorous waltz tunes than the hotchpotch of the Le Corsaire music, said to be by Adolphe Adam (of Giselle), but whispered to have quite a handful of duff hands concerned.

While Le Corsaire is a long, leisurely evening of ballet mime-show, with only a couple of really distinguished ballet numbers, the Paquita grand pas is the dazzling finale of what would have been a similarly languid and exotic entertainment, and opulently staged here as surely only the Bolshoi can, with courtiers, children and a catwalk parade of feminine beauty. It will seem almost criminal now for anyone else to stage Paquita without this luxury.

Paquita's Fabergé excess rounded off a triple bill much blessed by the newish Ratmansky Russian Seasons, which he created for New York City Ballet in 2006, and which now the Bolshoi claim by birthright and turn, with their eloquent Russian backs and necks, into a modern masterpiece.

It has fascinating music - 12 musical seasons by Leonid Desyatnikov for an enchanting variety of string orchestra and sung chants, and the soprano brought by the Bolshoi, Yana Ivanilova, has the voice of a nightingale, haunting, liquid, deeply stirring. To this inspiring tapestry Ratmansky creates a series of dance episodes involving six couples in different states of love, bookended by a pair whom we see in courtship at the start and about to be married at the end. There gradually builds, through the telling contrast in the dances, a sense of foreboding for the wedding couple, with shades of Les Noces (both Stravinsky’s music and Nijinska’s choreography). The naturalism of the way the boys and girls cluster, mingle, argue, is reminiscent of the best of Mark Morris or Christopher Bruce but the choreography is pure ballet, instinctively full of rich references back and technical enjoyment but vibrantly expressive of modern life. Friday's cast was superb, individualised and unafraid, particularly the passionately involving Anastasia Meskova in red.

I was very disappointed with the brand-new "restoration" of Petrushka, made from its choreographer Fokine’s notebooks, says Sergei Vikharev, but feeling strangely circusy and heavyhanded, rather than the folkloric and eerie ballet about the secret life of puppets that fascinated Europe in 1911. In this performance, both musically and choreographically every incident emerged like a 19th-century solo number, stagey and overstressed. I wanted Merce Cunningham to come in and iron all the self-consciousness out of them, put some random surprises and serendipity into this excited street scene.

The supernatural little story can’t emerge when the broken straw puppet Petrushka is reeling off double tours and virtuosic leaps, and the ballerina doll performs like a 21st-century competition entrant. Ivan Vasiliev, the magnificent Spartacus and an impressive solo act in Le Corsaire last night (the Pas d’esclaves), has not yet found the imaginative path to turn his athletic body boneless, hopeless, spineless. But Igor Tsvirko’s Moor was amusingly clumsy, his long face mocking himself as he hacked at his coconut with a cardboard scimitar (Tsvirko also caught attention in the Ratmansky). Still, this is a real let-down - Petrushka is such a Russian piece that we expect Russians to show us its spooky genius.

Add comment