Tim Henman - brilliant and unfairly treated, or... not? Even when John McEnroe passionately enumerates Henman’s qualities, do you both nod hopefully and realistically shake your head? Because, yes, our lad may be a rare craftsman of the grass court game, but if the point is giving us the shock of unexplained genius that is, say, Federer's (or McEnroe's) habit, then no chance, mate. And so to Richard Alston, whose court is dance, and the point of dance is to make you feel exultant, shuffle off your mortal coil, thrill to music and movement, feel the out-of-body tug of that other world which is theatre.

Alston has attracted radiant reviews from many critics, particularly in the US, but after an evening such as last night’s at Sadler’s Wells I remain, respectfully, unradiated. Yet I go every time as a would-be acolyte ready to be persuaded, and I mourn when yet again my notebook ends up full of complaints. It is about the lack of that e-word, exultancy. As with Henman, here is someone who has the right qualities - the technical ease, the application, the aptitude - and yet lacks that panache of risk-taking, because theatre is a dangerous place where you only succeed by staring failure in the face.

Two of the three pieces last night were Alston’s. I arrived so precisely for curtain-up that I didn't read which came first, and with an innocent eye started scribbling, “My, how Alston is discovering, in his sixties, something more youthful, the occasional unpremeditated throwaway gesture, the merest hint here and there of something offbalance. There is a little of Cunningham here in the squared yet destabilised torso, even a ghost of Mark Morris in the Puckish, squatting thrusts, despite the usual stolid walking on and off by dancers that kills the tension. Maybe,” I scrawled with relief, “this uptight choreographer is loosening up and his workmanlike style can become grace. Even if the Bach Brandenburg Concerti do still far outrun the choreography in their capacity to make my spirits bubble over.”

But it wasn’t Alston, it was his protegé, Martin Lawrance, who made To Dance and Skylark. I was taken in because the costumes were pure Alston - hideously unflattering, with shimmery elastic pants under big blue T-shirts, and the low slanting light by Charles Balfour that makes every leg look as white, heavy and bulbous as a parsnip. There was one parsnip-defying move, a romantic whirl by the men of their sleeping ladyloves round and round in the air (though I think I have seen that before somewhere). A few years back his Grey Allegro to Scarlatti felt clean and sharp; this one is much of a muchness.

Much of muchness can be said about Alston’s revision of his 1994 Movements from Petrushka. This is staged with nice theatricality, with a pianist and piano centrestage, Jason Ridgway playing the fiendish 1921 keyboard version of Stravinsky’s Russian ballet score from memory and with tremendously impressive command. Behind him a backcloth cleverly derived from the old Ballets Russes cloth of moon rising over Russian roofs, and before him two quartets of what look like Moscow eatery waiters in white shirts and black trousers - who in fact set up an opposition of men against women that has an intriguingly subtle flirtatiousness. Their dance is self-consciously “Russian”, with Alston inserting gopak-stype stomps, and it feels promisingly like a situation waiting for an event.

Between the busy ensembles comes Petrushka’s music, for which there is a lad in black, the eyecatching ingénue Pierre Tappon, in a spry solo displaying an elastic athleticism far from the puppet’s sawdust floppiness. The distance that Alston sets between the celebrated Fokine characterisation and his own is welcome, allowing poses of anger and distress in the lad’s choreography without evoking those emotions too dominantly. There’s a clever entrance then of the eight waiters, circling the piano yet allowing the soloist a fleeting leap to wave them farewell and exit the stage in an echo of Nijinsky. The anticipated event comes right at the end, an echo of Rite of Spring, as the lad faces the crowd, but too quick and unclear to register anything more than a dance history reference.

Ridgway’s piano-playing stresses how dansante Stravinsky’s marvellous music is, but also prompted yet again my usual wonder why Alston picks up on rebellious music that is so far from the rational, sober nature of his choreography, and which will always expose the mismatch.

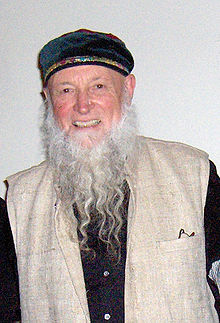

There is more imperturbability and unflappability on offer in his Overdrive (2003), a mechanical ensemble for 11 dancers set to a monochrome electronic keyboard study by the seminal American minimalist Terry Riley (pictured right). It is billed as “responding to excitement”, which it may well be, but generating excitement is something else. The relentless clacking of the minimal notes and grey empty stage evoke an earnest atmosphere of assembly lines, inhuman monotony, mechanistic ruthlessness, and the dancers’ busy, arm-flagging routine (wearing grey or red) is roughly on a par with watching expert aerobics in a gym. People walk in and out stolidly and perform a loop of movement: leg raise, knee bend, straight arm waves, leg flick. It seems to want to be considered turbo-charged, but actually is keeping well within the 50 mph speed limit.

There is more imperturbability and unflappability on offer in his Overdrive (2003), a mechanical ensemble for 11 dancers set to a monochrome electronic keyboard study by the seminal American minimalist Terry Riley (pictured right). It is billed as “responding to excitement”, which it may well be, but generating excitement is something else. The relentless clacking of the minimal notes and grey empty stage evoke an earnest atmosphere of assembly lines, inhuman monotony, mechanistic ruthlessness, and the dancers’ busy, arm-flagging routine (wearing grey or red) is roughly on a par with watching expert aerobics in a gym. People walk in and out stolidly and perform a loop of movement: leg raise, knee bend, straight arm waves, leg flick. It seems to want to be considered turbo-charged, but actually is keeping well within the 50 mph speed limit.

Does watching it make you envious? Do you want to be them or to be there? Do you wonder what fascinating thoughts and visions they are having? The way you do with Cunningham, Ashton, Morris, Oguike or Tharp? Maybe you do. I envy you.

- Richard Alston Dance Company performs in Sadler's Wells tonight, then tours until 19 June, with performances in Brecon, Brighton, Northampton, Norwich, Shrewsbury, Glasgow, Leicester and finally London's The Place.

- Check out what's on at Sadler's Wells this season

Add comment