What a difference a change of cast can make to a show. On Wednesday night I saw Tamara Rojo and Carlos Acosta as the titular lovers in English National Ballet’s Romeo and Juliet at the Royal Albert Hall (see below for that review). Last night it was the turn of ENB’s other Royal Ballet emigrée, Alina Cojocaru, and guest star Friedemann Vogel of Stuttgart Ballet.

Rojo and Acosta impressed me with their star power, and the intensity of their partnership, but left me feeling curiously un-tragic. Cojocaru and Vogel, on the other hand, had me spellbound like it was the first time I’d ever seen the story: surprised as they were by that coup de foudre in the middle of a stuffy party; tearfully thrilled by the balcony scene; desperately willing Fate to swerve over the sepulchre and let Juliet wake up in time; breathlessly applauding in the aisle, shaken enough not to care about the train I would miss by lingering. This is what Romeo and Juliet should be.

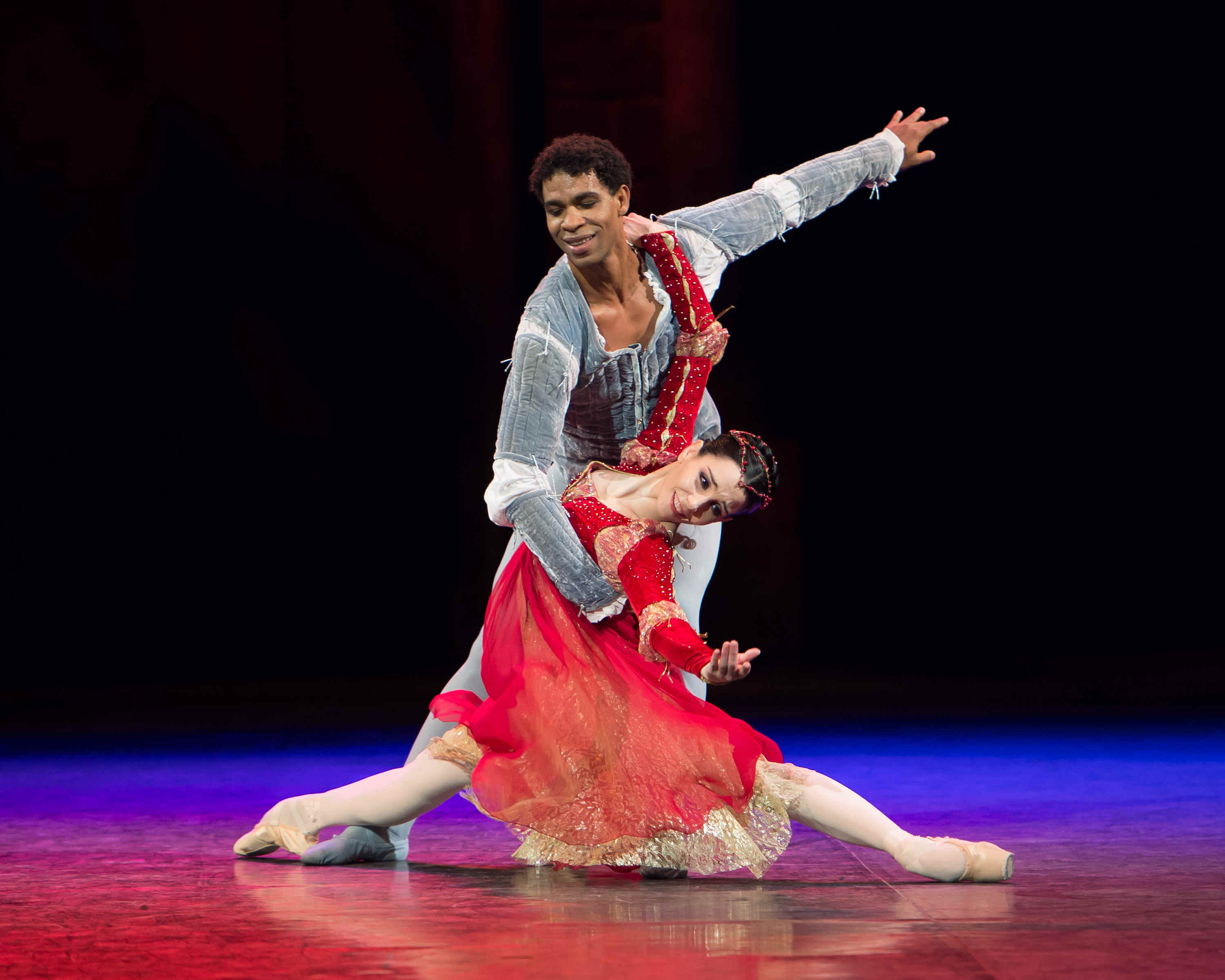

Cojocaru, at 33 and Vogel at 34, have the immense advantage not just of being younger than Rojo/Acosta but of looking it. Tiny, pale, slightly worried-looking Cojocaru perfectly embodies the gentle, intensely affectionate, sheltered daughter of a Verona family; slender, handsome, good-natured Vogel the confident but dreamy scion of another. At the ball, he seems so pleased to be talking to Rosalind (the character is preserved by Deane and played by Begoña Cao with memorable presence that bodes well for her turns as Juliet later in the run), she so distracted by obediently dancing with Paris (Arionel Vargas), that their encounter is a shock indeed. Cojocaru plays Juliet shy, hiding her face in her mandolin, while Vogel plays Romeo as tender, even reverent, trying to to impress her with jumps (good tactic, that: his jumps are stunning), but also to reassure her and draw her out with gentle smiles.

Cojocaru, at 33 and Vogel at 34, have the immense advantage not just of being younger than Rojo/Acosta but of looking it. Tiny, pale, slightly worried-looking Cojocaru perfectly embodies the gentle, intensely affectionate, sheltered daughter of a Verona family; slender, handsome, good-natured Vogel the confident but dreamy scion of another. At the ball, he seems so pleased to be talking to Rosalind (the character is preserved by Deane and played by Begoña Cao with memorable presence that bodes well for her turns as Juliet later in the run), she so distracted by obediently dancing with Paris (Arionel Vargas), that their encounter is a shock indeed. Cojocaru plays Juliet shy, hiding her face in her mandolin, while Vogel plays Romeo as tender, even reverent, trying to to impress her with jumps (good tactic, that: his jumps are stunning), but also to reassure her and draw her out with gentle smiles.

Both have an incredible gift for conveying delight, not just with their faces but in their dancing, which has all the speed, lightness and abandon of a truly great partnership. It’s almost impossible to believe that this is only the third time they have danced these roles, but for the freshness they bring to it. In the balcony scene, it’s as if they are seeing the world for the first time – astonished, and ecstatic. You are rooting for them at every moment – when they are married by gentle Luke Heydon as Friar Lawrence, when after their wedding night, they find it almost impossible to tear themselves apart, when Cojocaru, desperate and desolate, takes the potion. Her white-faced fear when she has stabbed herself conveyed like no other Juliet, with the horror of dying alone among those candles and corpses. But then she fairly broke my heart by climbing up to nestle beatifically beside Romeo, for all the world like a woman who has woken from a nightmare and settles with relief into her husband’s back to fall asleep again.

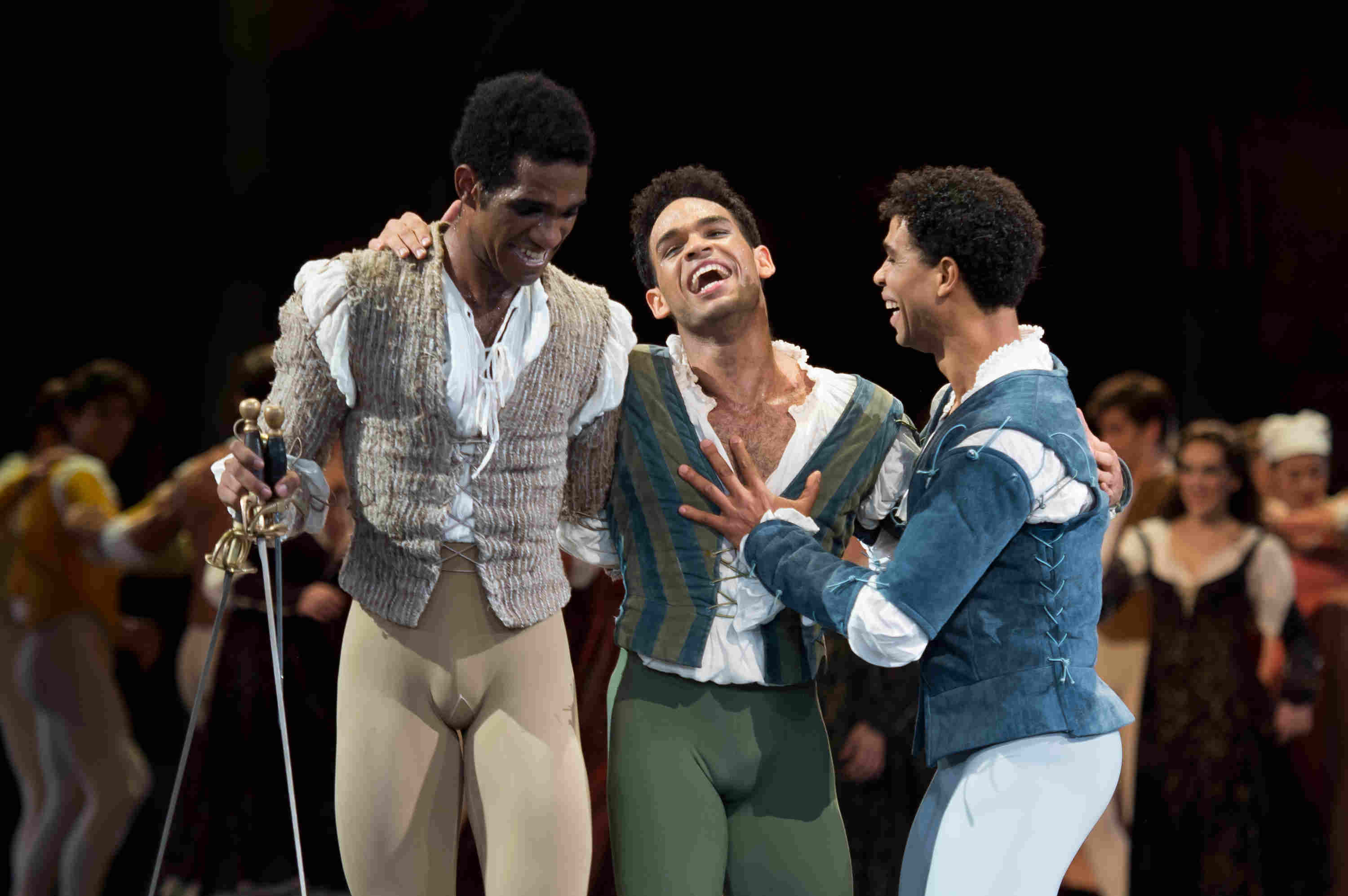

Excellent casting paired Vogel with the similarly shiny-haired, good-looking Fernando Bufala and James Forbat as Mercutio and Benvolio: they make a charming, ebullient trio, very light and crisp in their petits batteries. Barrel-chested Max Westwell is an angry, thuggish Tybalt, but with just a touch of confusion, reminding us that Tybalt too is caught up in events not entirely of his own making. Lauretta Summerscales, Nancy Osbaldeston, Ksenia Ovsyanick and Adela Ramírez, four of ENB’s top women, dance the Harlots – as they did on Wednesday – with character, charm, and verve.

I must confess that the power of the central story completely changed my assessment of Deane’s choreography. What on Wednesday seemed rather staid now impressed me with its simplicity, its naturalness, and its skilful use of the large round stage – unlike the regimented Swan Lake in the round, which took proscenium-front choreography and multiplied it by four sides, this choreography is always twisting and turning, offering something to every compass point without seeming to, and creating the busy, engaging atmosphere that is such a strength of plays in the round. Under Gavin Sutherland the ENB orchestra were really going for it, filling the RAH with lush waves of Prokofiev, full of strings and woodwind and bass, but easy on the strident brass.

With the right cast, this Romeo and Juliet is a supremely passionate, immersive experience – a tremendous night at the ballet.

First Cast Review (Thursday 12 June 2014)

It’s tempting to try and deduce what the young Tamara Rojo was like from Derek Deane’s 1998 Romeo and Juliet. Is it because he created his teenage heroine on this gifted, determined, magnetic dancer that Deane made Juliet the story’s driving force? Or do we think it's just because one of Rojo’s gifts is to make her every performance seem like a definitive interpretation?

Last night at the Royal Albert Hall she offered us a supremely confident, fiery and imperious Juliet. It’s an interpretation that suits Rojo’s position – aged 40, not only an international superstar ballerina, but the director of English National Ballet – but it also puts a new spin on the story, driving both Verona’s oppressive society and the terrifying ecstasy of teenage sexuality into the background and focusing instead on the wills of young aristocrats.

I suppose a family like the Capulets might well have bred a proud, sparky young woman who, cosseted and privileged, is accustomed to getting her way (presumably a type not wholly unknown here in Kensington...) This kind of Juliet is happy to flirt a little with a mild-mannered Paris (role debut Daniele Silingardi, looking nervous at having to partner his boss); when Romeo (Carlos Acosta) grabs her attention at the ball she masks her fascination in arch laughter; but when he appears under her balcony she is so hot for him – and sure of herself – that it looks for a moment like they might deny us all the famous pas de deux by scooting straight upstairs to the bedroom.

I suppose a family like the Capulets might well have bred a proud, sparky young woman who, cosseted and privileged, is accustomed to getting her way (presumably a type not wholly unknown here in Kensington...) This kind of Juliet is happy to flirt a little with a mild-mannered Paris (role debut Daniele Silingardi, looking nervous at having to partner his boss); when Romeo (Carlos Acosta) grabs her attention at the ball she masks her fascination in arch laughter; but when he appears under her balcony she is so hot for him – and sure of herself – that it looks for a moment like they might deny us all the famous pas de deux by scooting straight upstairs to the bedroom.

Complementing Rojo’s entitled Juliet, we had the excellent Fabian Reimair as a sneering, bully-boy Tybalt – the kind of viciously arrogant public schoolboy who’s used to pushing people around – and the Capulet parents (Jane Haworth and James Streeter) as hyperventilating nonentities, struggling to control their own emotions as well as their daughter, and so lurching impotently between theatrical grief and empty threats. It’s saved from being Cruel Intentions or The Secret History only by the extreme niceness and likeability of Rojo herself, Acosta, and the Montague boys (pictured above left). Not only is the perennially lovely Acosta on particularly cheerful form, his young nephew Yonah (pictured below right) makes an adorable spark of a Mercutio, minxily strumming on his mandolin and doing lovely big jetés. If he and Junor Souza’s admirably self-effacing Benvolio seem like frolicking puppies (no curse is spat on this Mercutio’s dying breath), it does at least fit with the production’s general tame-and-teenage theme.

Complementing Rojo’s entitled Juliet, we had the excellent Fabian Reimair as a sneering, bully-boy Tybalt – the kind of viciously arrogant public schoolboy who’s used to pushing people around – and the Capulet parents (Jane Haworth and James Streeter) as hyperventilating nonentities, struggling to control their own emotions as well as their daughter, and so lurching impotently between theatrical grief and empty threats. It’s saved from being Cruel Intentions or The Secret History only by the extreme niceness and likeability of Rojo herself, Acosta, and the Montague boys (pictured above left). Not only is the perennially lovely Acosta on particularly cheerful form, his young nephew Yonah (pictured below right) makes an adorable spark of a Mercutio, minxily strumming on his mandolin and doing lovely big jetés. If he and Junor Souza’s admirably self-effacing Benvolio seem like frolicking puppies (no curse is spat on this Mercutio’s dying breath), it does at least fit with the production’s general tame-and-teenage theme.

This is a production that relies on acting, rather than dancing, to tell stories: it’s a testament to ENB’s current form that they can field enough dancers with the presence to carry it off, but Deane’s choreography is unlikely to excite anyone familiar with those of Cranko, MacMillan, Nureyev, or even the rarely-performed Ashton. It doesn’t harm Rojo and Acosta – at this stage in their careers, they could both improvise the whole thing and still be tremendous – but it gives everyone else less to do. The corps de ballet are stage dressing rather than representatives of a particular society (these are the same anonymous onlookers who dance the harvest home with Giselle, or look concernedly at that dark girl Prince Siegfried is so taken with), and everything is sanitised. Even the four quaintly named "Harlots" have lovely velvet brocade dresses and shiny shampoo advert hair.

This is a production that relies on acting, rather than dancing, to tell stories: it’s a testament to ENB’s current form that they can field enough dancers with the presence to carry it off, but Deane’s choreography is unlikely to excite anyone familiar with those of Cranko, MacMillan, Nureyev, or even the rarely-performed Ashton. It doesn’t harm Rojo and Acosta – at this stage in their careers, they could both improvise the whole thing and still be tremendous – but it gives everyone else less to do. The corps de ballet are stage dressing rather than representatives of a particular society (these are the same anonymous onlookers who dance the harvest home with Giselle, or look concernedly at that dark girl Prince Siegfried is so taken with), and everything is sanitised. Even the four quaintly named "Harlots" have lovely velvet brocade dresses and shiny shampoo advert hair.

It’s a thrill to see Rojo back on her best form. In her last two story ballet outings she was in difficult classical parts (Swan Lake, Le Corsaire) with an unfamiliar partner (Matthew Golding). In Deane’s less demanding choreography, with the support of her long-time Romeo, Acosta, she is free to light up the Royal Albert Hall with her formidable charisma, leaving us in no doubt that she is still one of the greatest dramatic ballerinas of all time. As for the rest, it’s a crowd-pleaser, but only the Rojo-Acosta partnership has a deeper emotional resonance, not the story’s own horror. There is precious little of tragedy, or catharsis here.

- English National Ballet are performing Romeo and Juliet in the round at the Royal Albert Hall until 22 June

Add comment