To the international world of ballet, Clement Crisp was the British critic to fear for half a century. Crisp's dance reviews for the Financial Times – "the pink 'un" – from 1970 until 2020 were legendary for their passionate fastidiousness about ballerinas and high style, their acuity about rising talents and the difficulties of creativity, and – often – their ferocity, when he saw something he thought a blight.

They were written with an unstoppable effervescence and expressiveness in language that sent readers hunting down their dictionaries for words like "borborygm", or consulting parents about characters in early soap operas. His hatchet jobs were often a high form of comic literature, because he believed he owed the reader an entertaining few minutes, as well as the spectator a sound guide to the worth of what they had just seen.

But Crisp, who died in Sussex aged 95 on Tuesday evening, was profoundly devoted to the art of dance in whatever form it came, seeking out its seriousness of intention and accomplishment, viewing criticism as a calling he had felt from the first time he saw ballet as a child.

"My criticism is dictacted by a passion for organised movement, be it Mariinsky classicism or hip-hop or tango, and a need to provide some historical and aesthetic setting for it," he wrote in a volume of his reviews published last year, Clement Crisp reviews: Six decades of dance (edited by Gerald Dowler, see image left). "My anger is reserved for incompetent staging, for the traducing of the past, and for choreographers whose works are laden with intellectual pretensions, with flagday generalities, and who deform existing works through insensitivities worthy of Attila the Hun. Here, comment must raise weals."

"My criticism is dictacted by a passion for organised movement, be it Mariinsky classicism or hip-hop or tango, and a need to provide some historical and aesthetic setting for it," he wrote in a volume of his reviews published last year, Clement Crisp reviews: Six decades of dance (edited by Gerald Dowler, see image left). "My anger is reserved for incompetent staging, for the traducing of the past, and for choreographers whose works are laden with intellectual pretensions, with flagday generalities, and who deform existing works through insensitivities worthy of Attila the Hun. Here, comment must raise weals."

I was one of the breathless critics trudging with blunt weapons in his wake, a younger generation with no direct access to the history he had lived as well as known, constantly learning comparative values from his writing. And in 2001 I noticed that ballet fans - who treated dance critics as pond-life, on the whole – had done a poll on which reviewers they trusted. There was no contest – Clement Crisp won an overwhelming share of the vote.

That year, Crisp happened to be claiming he was turning 70, so I asked him to give me an interview for the now defunct website Ballet.co.uk, incorporating questions from those devotedly trusted ballet fans. (I did not realise at the time that he had long been concealing his true age, and was actually 75, though Who's Who and all the official dictionaries still say he was born in 1931.)

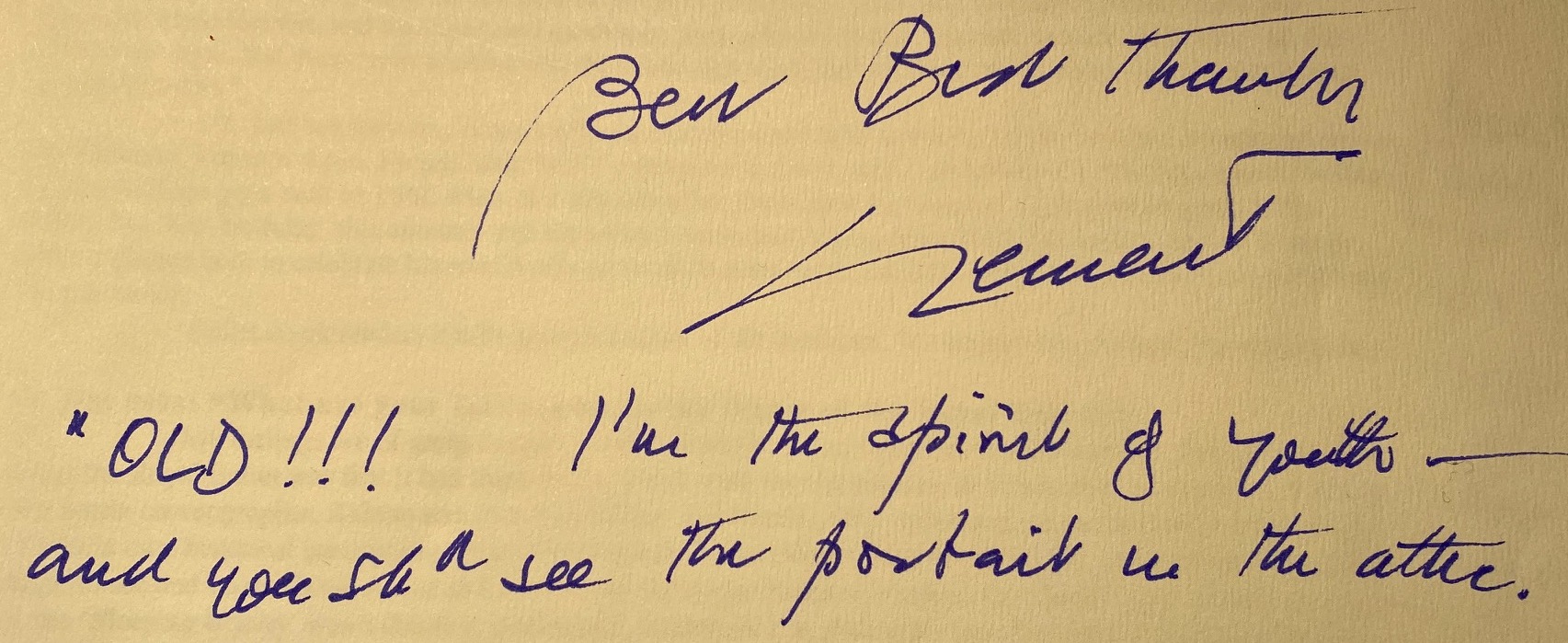

Our interview was a hoot because Clement rose to the occasion with all his base performer's instincts, as well as his inner teacher. He kissed and he killed with precision and abandon, and he asked for nothing to be expurgated when I gave the transcript to him to check – except for the adjective "old". ("Oh! How cruel!" he scribbled in the margin.)

Clearly our conversation was about then, not now, and many 2001 assessments and questions were overtaken by events. The new director of the Royal Ballet, Ross Stretton, was an unknown quantity, and would last only one very controversial year in the post. The impact of new contemporary creators on British and world ballet lay in the future, gamechangers such as Wayne McGregor, Akram Khan, Christopher Wheeldon and Alexei Ratmansky. Some of his targets in our interview have much more nuanced and even affectionate treatment in the new anthology, Clement Crisp Reviews.

But the flashing passion, curiosity, relish of theatrical cut-and-thrust, and rather innocent hopefulness that lay behind Crisp's outlook were part of his nature, and would never change. While he was often furious, sometimes even found objectionably personal in his attacks, he was never jaded. For him, the point was to have the argument out and sit down together for the next curtain-up.

The contemporary choreographer Siobhan Davies remarked of Crisp's combativeness: “I realise that his desire to write of dance in the way he does, stems from a deep understanding of the art, from affection for dance and dancers – and sometimes from frustration when dance is not well served by its creators or interpreters.”

Here, in tribute to a titanic source of priceless knowledge, writing artistry and sheer personality, is the 2001 interview.

Crisp commands English like a maestro controlling a vast orchestra of thousands of instruments, some splendidly abstruse

Clement Crisp invites me to lunch at his flat in Westminster, inside a large, gleaming Thirties apartment block with all the splendid elegance of an ocean-liner. It seems a most suitable residence, given that his taste and standards in ballet are rooted in the monumental achievements of the Ballets Russes and the artists who issued out of that extraordinary little group to colonise the world with ballet.

The walls of his flat are hung copiously with ballet images – designs, paintings, photographs and pictures of ballerinas, his favourites evidently being Natalia Makarova, Ludmila Semenyaka and Alicia Markova. Lunch is champagne and smoked salmon with salad. I tell him that in an internet poll Ballet.co.uk fans declared him, by an almost unbelievable margin, the critic they would most trust. He cackles, throwing his head back (rather like a rooster crowing).

It’s an explosive, arresting sound, one of the most recognisable laughs to be heard inside the London theatre and when you have placed it to this tall, white-haired, bespectacled and impeccably smart gentleman, it makes you study his face in a quite new way. You suddenly notice the pointy way those eyebrows fly upwards and outwards, the sharpness of his eyes behind their glasses.

No critic can kebab shoddy or vulgar work as cleanly and as ruthlessly as Clement Crisp; yet his kebabs come fronded with savoury, fascinating, even eccentric references to classicism, literature, TV soaps, bizarre current events, music hall acts, bits and pieces of magpie information – a cultural garnish sometimes tastier than he found the particular matter in hand.

Here he is kebabbing Ohad Naharin’s Sabotage Baby at the Barbican this year:

“The 'music' was actually very jolly. It was provided by Orkater, a Dutch ensemble which manufactures din from a complex of machines and gizmos that lurk at the back of the stage. Peter Zegveld and Thijs van der Poll (the musician/ machinists) busy themselves furiously amid this deranged gamelan, which is a cross between the Titfield Thunderbolt and Da Vinci's prototype for a Teasmade. Crazed tootlings, fearful borborygms, the occasional twang, fill the air, while Naharin's hapless cast lumber about, by turns lethargic or frenetic...

"As the evening wears suicidally on, four figures on stilts, sporting teeny feathered knapsacks and expressions of direst menace, totter above the common herd (and few herds have looked more common than these straining performers). I hoped they might have come from some pest-control agency.”

Crisp commands English like a maestro controlling a vast orchestra of thousands upon thousands of instruments, some splendidly abstruse. Readers scurry to their dictionaries. Ballet, which of all the performing arts offers the highest challenge to any attempt to express it in words, has produced a tiny handful of star writers able to match the brilliance of the achievements they saw on stage with their own verbal artistry. Edwin Denby, Arlene Croce, Richard Buckle and Clement Crisp are critics whose criticism lives an independent life as wonderful pieces of writing (whether you trust their contents or not), the virtuosity underpinned by the seething passion and important knowledge with which they form their judgments.

Newspaper English is nowadays more functional than stylish, but Crisp keeps style alive, prodding language insistently with everything from brutality to decorative hyperbole, as if English were a sluggard that would never get out of bed if he did not lash it with his borborygms and Teasmades.

When he likes something or someone, I imagine they must feel, as they read the black print on the pink paper, as if they were being showered with rare jewels. As Tamara Rojo might have felt reading his appreciation of her first Royal Ballet Swan Lake a year ago:

“[Rojo's] actions speak so loudly that we need no words. The Swan Queen grieves and hopes against hope, and we know every nuance of feeling. Her Odile is malign, seductive, and dazzles Siegfried – as she dazzles us – with prodigies of steps. The third-act fireworks flared and glittered: triple fouettés, and the occasional quadruple; long-held and steady balances; musical sensitivity – all this told of her style. But even more exciting was the poetic sensibility that coloured every action. She is a fascinating young ballerina.”

He does not have any contact with the Internet, apart from knowing that his reviews are beamed out on the Financial Times website. He has been the FT’s dance critic for 35 years, and The Spectator’s for four. His knowledge goes back to 1942, when as a schoolboy he discovered the magical experience of going to the ballet.

His 70th birthday this autumn, and the seismic shifts now taking place in British ballet, seemed to me to offer a chance both to celebrate his remarkable gifts and to draw on the valuable insights of an almost uniquely long-lasting career. Ballet.co.uk readers kindly provided many of the questions. We began with, perhaps, the obvious one.

A critic who saw the first performance of Sleeping Beauty in 1890 could still have been writing in the 1950s, looking at the Royal Ballet’s Sleeping Beauty and saying, Well, it wasn’t quite like that. Which is a thing I can do

ISMENE BROWN: Jim asks: “What are your feelings about the future of the Royal Ballet?”

CLEMENT CRISP: My feelings are of despair. I really think the Royal Ballet has been denatured. The great point about the Royal Ballet was that it had three bases, which were the old classics, in honourable productions; the work of a house choreographer, Ashton and then MacMillan, and Cranko, very important; and a sense of history - Dame Ninette’s own historical perceptions about choreographers like Fokine, Massine, Nijinska, masterworks that people ought to see and know about. As far as I can see, we have now traduced classics: the Swan Lake [IB: Dowell-Sonnabend] is hideous to look at, the Sleeping Beauty [IB: Dowell-Bjørnson] was a disaster, malformed, destroyed. I’m glad to see that Coppélia came back looking all right, the Nutcracker is okay. But of course what has gone is the ability to dance these works properly. There is not a single dancer in that company of native training who I think is fit to dance those ballets.

Not Darcey Bussell?

No.

Miyako Yoshida?

No. They are no more than first soloists, essentially, if we look at performances of Swan Lake, Beauty, Giselle, Coppélia, by the absolute standard of the world. And this is the thing one could do, from very early on, with performances by Margot Fonteyn, Beryl Grey, Pamela May and Moira Shearer, who were all world-quality; and then of Nadia Nerina and Svetlana Beriosova, and then of Lynn Seymour and Antoinette Sibley and Merle Park. I do not think now there is a single dancer in that company of world quality who has been produced by the native tradition.

The interesting thing is that they did get Irek Mukhamedov, and now they’ve got Tamara Rojo, which is wonderful. They have Alina Cojocaru, Carlos Acosta, Johan Kobborg.

But these are all outsiders.

Yes.

It’s [previous Royal Ballet director] Anthony Dowell’s fault, and Merle Park’s at the school?

Yes, indeed, and the school.

That generation of dancers, which was so accomplished, didn’t know how to pass it on, did not understand the urgency of the need.

And they had no understanding, it seems to me, of the past. Some of the Fokine repertory comes back, a bit of the Nijinska, occasionally – but I’ve always believed that a company like the Royal Ballet should be full of dancers who know the stylistic differences between Petipa, Nijinska, Balanchine, Massine, Fokine – and also had those works in their bodies, just as any pianist will know his Bach, his Beethoven and Mozart. If you don’t have that kind of general knowledge in your body, even as corps de ballet, everything has to be “retaught” and reinterpreted and further degraded each time. The great thing about Russian tradition is that everything is nursed and looked after, it is rigorously handed down, and there is no fooling around with changing this, changing that – as Ashton has been changed, shall we say. Style is going, so that you must accept dancers kicking their legs up in the air in entirely the wrong places. That occasionally happens in St Petersburg too, of course. But it was interesting that the great Aurora we saw this summer from the Kirov was Janna Ayupova, who was markedly better than that tedious Svetlana Zakharova kicking her legs up into six o'clock all the time.

And then one looks at a Royal Ballet repertory which brings in Don Quixote, which the Royal Ballet is never going to be able to dance, not even as well as the Paris Opéra, because they don’t have the right coaching. They have no one who understands the energy, the vigour, the panache. I expect it’s just going to look rather flat. Mmm?

So that’s what has gone wrong so far. Is the future going to be better?

No. We don’t have a choreographer. We don’t have a music director. We have an artistic director [IB: Ross Stretton] who I think does not understand what the Royal Ballet is about. He has never worked with the company, I don’t think he understands what has made the company tick thus far. I mean, look at the fact that he brings in Mats Ek, who is an enemy to ballet, or that tedious Nacho Duato. What does this have to do with British ballet? Nothing at all.

Jonathan Burrows, Michael Corder, Russell Maliphant, Matthew Hawkins, Matthew Hart are all British choreographers who have made interesting work. Why have they not been encouraged in, to start with short workshop pieces, if you like? The understanding of classical dancing, or what classical training really means, is absolutely vital before you start, because if you don’t speak the language you can’t do anything with it. Whatever Jonathan Burrows may do – and I think he’s actually a deeply fascinating creator – whatever he does comes from the fact that he’s known classical dance for 20 years, and he’s said, "No, I don’t want to do that, I want to do this," and he knows why.

No unprejudiced criticism is worth reading. Or worth writing. Prejudice is what makes a critic interesting

Stretton has brought in repertory that he thinks is going to do the company good in some fashion.

Oh ho! Well. Interesting to see what good Mats Ek can do anyone. And Nacho Duato, this terrible, wambling, woolly soft-at-the-edges Jirí Kylián style which is so unmusical, and so repetitious, and so lacking in any kind of rigour.

I think the answer for the future of the Royal Ballet, if it is not to be destroyed by perfectly well-intentioned but entirely ignorant people, is that it has got to look to its own creatures. And I suspect the creature it has got to look at is probably Bruce Sansom. He seems to me the most likely choice for the future. [IB: Stretton's deputy Monica Mason would replace him a year later. Sansom went to San Francisco Ballet as assistant director.] The problem is, however, the exigencies of the Board and its planning. I love the way they plan opera three, four, five years in advance, whereas with the ballet season they don’t even know what they are going to do next year, and they don’t know what the casting is in a month’s time. All this waiting for Onegin casting is a scandal.

But you’ve got to think frightfully hard about where the Royal Ballet came from and how to encourage choreography. Given two studio theatres now in the Opera House, you’ve damn well got to have an extremely serious, probably expensive, certainly rigorous selecting of young choreographers, and someone there to talk to them, like several Dutch uncles. It’s what Sir Fred did for Kenneth. Someone who has a very wide experience of choreography – like Donald MacLeary, perhaps – someone who can help these choreographers, tell them, No, you can’t use this score. Or, why are you doing this ballet about the life of a barn owl when you know you should be thinking about steps?

And there is no music director. Barry Wordsworth, who is the rightful tenant of that post, is not there. When Madam started she had not only Markova as ballerina, who could dance anything beautifully, and the baby Fonteyn, but she also had the most vital figure of all, Constant Lambert. Lambert was a genius. Lambert was a brilliant musician, and he was extremely cosmopolitan and he had the most dazzling intelligence. Lambert could say Yes and No. He was not provincial or parochial, and so when the company began, it was not provincial or parochial. The Board today, I think, is largely comprised of people who don’t know what they’re talking about in ballet.

Has that not often been the case?

No. When Lord Drogheda was chairman of the Board, he was a brilliant and great man, and he decided you had to have the best, all the time. And David Webster knew what was good musically and what was good visually, and he insisted on getting the best. You look at the list of artists that Madam had in, her insistence on the visual picture.

Now I’m sure Ross Stretton is a very able and distinguished man, but I do not think he is right for the position he holds. The idea that you somehow suddenly attract a New Audience by putting on New Work is a pathetic fallacy. The ballet audience is by and large people in their 30s, 40s, 50s and so on. It is not the kids who want to go out dancing and drinking and going to clubs. And the idea of offering them little teases - okay, they’ll come and see a programme where there’s something shocking going on, but will they come back for Coppélia? Uh-uh.

I blame the BBC, the BBC does nothing now for ballet. When I first worked with the BBC I worked with a wonderful man, Richard Somerset Ward, who used to put on an entire month of programmes about ballet. Now we get a grudging transmission: “Oh, we’re going to show something in the piazza”. Aren’t people lucky to be able to stand or sit or squat in a freezing cold piazza to get the crumbs from the rich man’s table? It’s hypocrisy. Lip service to a fatuous idea.

Pete asks: “How do you feel the standard of ballet these days compares with that of past decades?” I’m not sure what he means by “standard of ballet” since it comprises so many factors...

No. Nor do I. I think several things have gone. No one has learned how to make a comic ballet. Nobody knows how to make a triple bill now. The Ballets Russes used to do what was called "ham and eggs" - Swan Lake Act 2 or Les Sylphides, then a serious ballet in the middle by Antony Tudor or whatever, then you’d finish with a Massine, a Boutique Fantasque or Gaieté Parisienne - a wonderful triple bill, with all your stars. Fantastic stars. How many ballet stars are there now in the West? I think Rojo, yes.

Sylvie Guillem is a star.

Hm. She’s not a real star.

She is a real star. You are wrong. You can’t compare her with old stars, she’s a different kind of star, but she is a star of top magnitude.

She fills the theatre, but she’s so uncompromising.

That’s why she is a star, because she is uncompromising.

I think she has a closed mind, artistically speaking. I would rather watch the Trockaderos’ Giselle than hers. I said it in a review.

Back to the question of standards.

I think standards of interpretation have gone down. Personality has almost completely disappeared. When Nerina and Beriosova danced, everyone was fascinated by these personalities. And Sibley, Dowell, Wall, Seymour. When the Balanchine company first appeared it was filled with the most extraordinary characters. The choreography had more flavour. The original Theme and Variations done by Alonso and Youskevitch was astoundingly beautiful. If you want to understand how Palais de Cristal was done in 1947 at the Paris Opéra, look at the Kirov doing Symphony in C now. That’s the way to do it. And funnily enough the way they do Apollo, too. Veronika Part? Sex bomb! Wonderful.

Yes, but the American balletomanes on the net made very sharp comments about that, called it yukky over-sexualisation.

Of course they did! Balanchine once said that Apollo was “like a farm boy”.

Next question, from Lily. “Will you be updating the Ballet-goers’ Guide in the near future?”

No.

Any books in the pipeline?

No, I’ve been asked to do about five, but I’ve said I’m too bored. I don’t think it’s interesting. There are so many bad books and I’m not going to add to them. [Crisp has already published 14 books, several with Mary Clarke or Peter Brinson.]

Question from Helen: “In what ways do you think ballet in Britain has changed during your career as a critic?”

Every possible way.

Just got worse generally?

Yes! We have stopped being a nation of ballet choreographers, we have stopped being a nation of interesting ballet-dancers, and we have stopped being a nation who go to ballet to enjoy ourselves.

And are they linked?

Yes, of course they are. The fault is largely that, financially, life has become so difficult for ballet companies that they not only have to play safe - Manon, Romeo and Juliet, Swan Lake - but they have also in a sense been corrupted by the success of modern dance. You see, where once these were separate and admirable manifestations of dance, there has been this gradual cross-pollination, so that people have forgotten how interesting a new ballet could be.

I wish people could have seen how that wonderful choreographer Walter Gore produced ballet after ballet after ballet, season after season, and when he got stuck, Kenneth Rowell, the designer, who was a great friend of mine, told me, “I used to give Wally a prop, a chair or a cup or something, and Wally would then start to make more steps.” Nobody is able to make ballets like that now, because everything is so hung around with bills.

One of the most interesting new things I saw was a couple of years ago, when I was on the jury of the first Peter Darrell choreographic competition, and the decor for this piece, which was to Stravinsky’s Renard, was a chicken coop, which must have cost all of £2.50. Marvellous. And then you see what the Opera House puts on for the latest masterpieces of Ashley Page and William Tuckett.

You could see every single company you wanted to see in London after the war. By 1960 we’d seen everything. I had a sensational education. Everything I do now is conditioned by the fact that I saw such good dancing

An American dance writer, Mary Cargill, asks: “I would like to know what kind of training, official and unofficial, he had, and what qualities he thinks a good critic needs.”

I had no training at all, I started going to ballet when I was 10, and loved it. If I’ve been educated at all it’s by watching every possible form of dance, all round the world, except Australia – yet. And I was very fortunate in that I saw an enormous number of very great dancers when I was very young: Lifar, Dolin, Markova, Danilova, Fonteyn, Helpmann, all those, and some wonderful Russians like Shelest and Plisetskaya, Ulanova, Sergey Koren, and real stars, Tamara Toumanova, Tatiana Riabouchinska. It was so easy to go to ballet, so cheap. I used to go to Sadler's Wells four times a week, back of the pit stalls, 2/6 a time.

I was also fortunate that although I knew very few dancers they were very great, and were prepared to talk about what they did. I learned from people like Vera Volkova [the leading London teacher], who was terribly funny and enormously illuminating. I still do learn from Markova – Alicia Markova was my university.

And people like Lincoln Kirstein, who was absolutely fascinating. Lincoln, who was a genius, devoted a large part of his genius to making it happen for George Balanchine, which is the most devoted, selfless activity you can imagine. He told me the truth about the whole Balanchine enterprise. He discussed how things were, what was going to happen, what he wanted. From 1933 to 1948 – 15 years – until they went to the City Center, they lived a lot of their life in a wilderness. But Lincoln believed that Balanchine was the greatest choreographer of the 20th century, and he made it possible for him to make dances. It is that American thing that I find so admirable, that you have to give art to society. You do it by founding a library, or giving huge sums to a museum, or you pay for an operatic season. What Lincoln did is part of a great tradition that still continues.

It is the phenomenon that stands out in the 20th-century story of ballet, isn’t it? Now the second part of that question: the qualities of a good critic.

Don’t bore people. Tell them what you see. Do your homework.

And don’t be prejudiced?

Oh, no unprejudiced criticism is worth reading. Or worth writing. Prejudice is what makes a critic interesting.

What are your prejudices?

Pro. Love of classical dancing. My prejudices are for, essentially, very beautiful Russian-trained dancing, for New York speed, for French temperamental virtuosity and physical virtuosity – their need to show who they are.

Anything English?

Oh, yes. At its best, English lyricism can be very beautiful, you see it in the work of Ashton. My prejudices contra are pretension, messages, the week’s good cause, flat feet, unstretched bodies, dancers with no necks. Unmusical dancers. Dancers who are not old enough – sending out boys to do men’s work, sending out girls to do women’s work. I think many dancers are at their most beautiful when they are over 40. I really love 40-year-old ballerinas. They know so much.

Sarah asks: “Please could you tell us how and why you became a dance critic?”

It was Andrew Porter who gave me my chance as a critic. We had met at Oxford. He was already a brilliant critic in his early twenties, and in 1953 he and Derek Granger, a most gifted theatre critic, started the Arts Page on the Financial Times. After about three years Andrew invited me to contribute occasional reviews. The page expanded and I wrote more and more, and in 1970 when Andrew went to New York, I took over all the dance reviewing.

Tell me about your schooling.

I went to a very good school during the war, in Surrey, Oxted Grammar School. Everyone tends to dramatise the war now, but you just lived and got on with it. I went to the ballet about every couple of weeks. It was only an hour on the train. I would budget it, have a glass of milk and a bun for lunch, then go to either the New Theatre or the Prince’s, see a show, and be back home by six. During the war, sometimes they gave three performances in a day, at 12, 3 and 6. Moira Shearer told me a very funny story about going down on stage for Les Rendezvous and finding two other girls who also thought they were doing the lead.

Helpmann was also terribly important. He was so funny, so fascinating. Not much as a dancer but a staggering artist. Very good in Façade - why do the Royal Ballet never dance Façade now? His Hamlet, Comus, The Birds... not bad. And his fascinating face, the mouth, the eyes...

And you could see every single company you wanted to see in London after the war. By 1960 we’d seen everything. The Danes made their first appearance, the Paris Opéra came. We’d had Roland Petit’s company. The last great relics of the Diaghilev company, the relics of the pre-war Ballet Russe company, and then all the major artists of the Royal Danish Ballet, the Paris Opéra. And ABT within seven years of its foundation, and City Ballet within two years of its foundation. Such variety, such wit, such style, such beautiful design, and such good music - I had a sensational education. So everything I do now is conditioned by the fact that I saw such good dancing.

I think of the longevity of people like Mary Clarke, Kathrine Sorley Walker, John Percival, Clive Barnes and myself. I’ve been looking at ballet since 1942, damn nearly 60 years. If you think, a critic who saw the first performance of La Bayadère in 1877, or the first performance of Sleeping Beauty in 1890, could still have been writing in the 1930s or even 1950s, looking at the Royal Ballet’s Sleeping Beauty and saying, "Well, it wasn’t quite like that." Which is a thing I can do, which John can do, and Mary, and Clive and Kathrine. That is a very important thing for a critic.

Can that get in the way, though, of allowing times to change?

No, because we have changed with time too.

I mean, in the sense that people who judged the Ballets Russes who came from 1890s St Petersburg would have been shocked by Diaghilev - if you are brought up on the values of the Forties and Fifties, can’t it impede the acceptance of the changes that contemporary dance has effected on it, and this new face that ballet needs to turn to the world?

It is not a new face, it is a corrupted face.

You referred to the importance and influence of contemporary dance, but actually the audience for that remains very small in comparison with ballet’s.

Yes, but we do not have in classical ballet in this country two choreographers as significant as Richard Alston and Siobhan Davies. And there are more interesting people making contemporary dance than in ballet. Would you give me the names of three important classical choreographers in the world today? Roland Petit. John Neumeier. Wheeldon.

I also think William Forsythe is extremely important.

If you switch off the machine, we will talk about Forsythe. [He then lays into him with energy.]

Next question is from Martin Jay: “How much attention should artistic directors, companies and dancers pay to critics?”

For the most part, none at all. Most criticism is trumpery and pointless, based on ignorance rather than knowledge. I’m not blowing even the smallest trumpet for myself, but I do worry about some of the comments I see. Inevitably criticism is important, and it must be there. Many dancers don’t read criticism, many directors don’t read criticism. Well, okay. Criticism is written for the public, to tell the public something about the thing the critic saw the night before.

So who should artistic directors take notice of? We critics are all going to take advantage of our organs to express our opinions of Stretton’s achievements - should he take a blind bit of notice of what any of us says?

Hm. Not yet. Watch the box office. I think the box office is going to die the death. I think there are already very serious box office problems there. Broadway 80 percent down, business everywhere is suffering, and I think the Opera House is among them, when you’ve got to pay £50, £60 for a ticket.

Kevin Ng asks: “Do you see any likelihood that a genius choreographer will emerge in this century of the same calibre as Petipa and Balanchine in the last two centuries?”

Who knows? It’s an unanswerable question. I’m not a crystal ball.

I took Ludmila Semenyaka to see Alicia Markova for tea and they fell in love with each other straight away because they spoke the same language. I listened and thought these two girls are 50 years apart in age but they both came from the same place

Wendy Glavis has four questions: “What are the high point of your career so far? (any low points?)”

Oh, yes, many high points. Great dancers. One’s first sight of Ulanova in Romeo and Juliet. Plisetskaya in Don Quixote - phenomenal. Fonteyn’s Aurora. Markova in Giselle and then Swan Lake. One’s first sight of Makarova, one’s first sight of Irina Kolpakova and of Ludmila Semenyaka. And Margrethe Schanne. It was nearly always falling in love with ballerinas. Nina Vyroubova I adored beyond belief. So expressive, so Russian. Lifar was wonderful, the first sight of him. One’s first sight of the Bolshoi, one’s first sight of the Kirov, Yuri Soloviev, Baryshnikov.

You have not once mentioned Nureyev.

Yes. I thought he was [sighs] a "star". A great star, but not a great dancer. I mistrust that sort of stardom, that doesn’t come out of technical command and a kind of serenity.

Alexandra Danilova, who was so funny, so beautiful, so witty, elegant. Odd things... you remember Evelyn Hart? One of the most transcendant moments of my entire career was seeing her dance Giselle in Vancouver. If I talk about great Giselles, I say, there were three or four. Like Markova, Makarova, and Evelyn Hart too.

You haven’t mentioned Gelsey Kirkland.

No. Neurotic. Mannered. If she’d stayed with Mr Balanchine she would have been a much more interesting dancer.

Suzanne Farrell?

Was a very interesting dancer, but not as interesting, funnily enough, in some of her roles as Uliana Lopatkina. Lopatkina is something very, very extraordinary. Just as Ayupova is a throwback.

You see, one of the things I love, and is terribly important to me, is a sense of continuity, of lineage. I do love to see where a dancer has come from in their performance. You can see in Ayupova’s dancing that she goes back 20 years, and that that goes back another 20 years by way of her teachers - and so on!

Alla Shelest, who made a few appearances in England, was a very great dancer. I remember Grigorovich saying, “I married my first wife for her intelligence” – that was Shelest – “and my second for her beauty” – that was Natalia Bessmertnova.

I think also with choreography there was the first time one saw anything by Balanchine. And I’ll always remember the first night of Ashton's Scènes de Ballet, how thrilling it was. And the first night of Mayerling, which was really quite tremendous. Do you know, once upon a time the Royal Ballet asked us to watch the dress rehearsal so that when you went to the first performance you were slightly armed with understanding. I was fortunate enough that the FT gave me plenty of space and I was able to review all three casts, David Wall, then Wayne Eagling, then Stephen Jefferies, and I wrote in excess of 1,000 words on each performance of what I think was a deeply fascinating work of art. You can’t have that nowadays.

I think strange things like Lifar dancing his own Icare was totally marvellous. I loved a dancer called Serge Peretti at the Paris Opéra, so clean, so elegant. Yvette Chauviré. Nerina on the first night of La Fille mal gardée is totally unforgettable. Ondine, I love Ondine very much indeed.

Did you like it as much this time around?

Do you know, in a funny way I thought one saw it better with Tamara Rojo, because the entire apparatus and focus was not directed at Fonteyn. You saw how brilliantly Ashton had put water on the stage. I wish Palemon had been danced by Mukhamedov, he would have done something with it.

What I constantly remember are performances. Irek in Giselle, ultimately the best Albrecht I’ve ever seen. When one saw Nina Vyroubova in Balanchine’s Night Shadow, a version of La Sonnambula, you were so drawn into her imaginative world – she was so attractive, one so loved her. It is of course a love affair – I think one’s relationship with dancers is a kind of love affair. I remember the back of Makarova’s neck is so beautiful, Semenyaka’s speed and that ravishing placing of the foot – how Russian ballerinas offer their foot to the ground, that’s what you look for, it’s in training, it’s the lineage thing.

I remember taking Luda [Semenyaka] to see Markova for tea and they fell in love with each other straight away because they spoke the same language. They were talking about variations, and Luda knew the variation Markova was talking about, “Oh, I know, it was Pavlova’s variation that I was taught.” And they were talking about Casse-Noisette and the double gargouillade, which no one can do now. And I listened and thought, these two girls are 50 years apart in age but they both came from the same place. A lot of dancers now, I don’t know where they come from.

With Elisabeth Platel you see that French bloodline back through Chauviré. With Vyroubova one goes back through Trefilova. You know at the end of the entrée in the last act of Sleeping Beauty, Aurora goes right down onto the ground, puts up her hand and the Prince takes it and she rises up – when Markova did that, she came up so slowly, there was such strength in that foot and leg that you couldn’t believe it. Everyone now just comes straight up. I said to her, "Where did you get that from?" She said, "From Madame Trefilova." Another Russian I saw did the same thing and she said, "Oh, it was the old tradition."

I love going to the theatre, I love seeing the curtain go up, I love anticipating what I’m going to see. I look forward to every single performance. Except by Nederlands Dans Theater

Wendy Glavis again: “At this point in your career, do you think being a critic has blunted your enjoyment of ballet or enhanced it?”

No, absolutely not! I love going to the theatre, I love seeing the curtain go up, I love anticipating what I’m going to see. I get terribly excited, and I look forward to every single performance. Except by Nederlands Dans Theater.

Her follow-up: “Are there any ballets you never want to sit through again?”

Hundreds. Do you want names? The entire works of Ashley Page, every single step. Every single step of Jirí Kylián except his version of L’enfant et les sortilèges, which I think is absolutely marvellous. The entire works of Mats Ek, the works of his mother, Birgit Cullberg. Endymion by Serge Lifar, which was perfectly terrible. But there are too many, too many. The works of Boris Eifman that I have seen. The works of that man in Monte Carlo, Maillot. Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker - all of it.

So which choreographers do you think are actually most life-enhancing at the moment?

First of all, Paul Taylor. Roland Petit. Christopher Wheeldon. Most of Mark Morris. Siobhan Davies.

Merce Cunningham?

Yes, Cunningham now. I think early Cunningham was a bit tiresome.

On the subject of how you express yourself in print, this suggests a question about the extremeness of passion with which one reacts for or against things - can this be a hazard?

Not a hazard, it’s a merit! [He is shouting again – he reminds me faintly of Patrick Moore, another rather sudden shouter.]

To be very for or very against?

Yes, of course.

Is it not more truthful to hover half-way if necessary?

No. Kiss ’em or kill ’em. There is no point in half-measures. People who write half-measures, like a lot of critics nowadays, are just boring. And not only boring, but lying.

But is it fair?

Whoever said the theatre was fair? Criticism is not fair. Criticism is a matter of prejudice. My prejudices against your prejudices. You might think Sylvie Guillem is a wonderful dancer, I respect you for it, but I think a lot of the time she is tiresome, and I want to shake her, because there are such good qualities going to the bad.

I think good writers sometimes write bad books. Unlike Darcey Bussell, who is a weaker artist, and who is sometimes lucky enough to be put into something in which she looks quite marvellous.

She should have gone to New York City Ballet.

Carly Gillies asks: “I know you had a great respect for Peter Darrell... in the present troubles of the Scottish Ballet, how important is any artistic director to the quality and direction of any ballet company, and does its future depend on the qualities of the artistic director? And what should these qualities be?”

Yes! Of course it depends on the qualities of the artistic director. I think Darrell should never have gone to Scotland in the first place, but he made a great success of it anyway. I think any company reflects its artistic director. It’s his extra-terrestrial body, his doppelgänger. I know of no good company that is directed by a bad artistic director. I know many indifferent companies that have been rescued by a good artistic director.

How would you say The Royal Ballet reflected Anthony Dowell over the last 15 years?

In the repertory and the quality of the dancing. That has nothing to do with his own dancing. You can be a perfectly good dancer and an indecisive artistic director. The proof of the pudding is Dowell. I think with an institution the artistic director is often shackled. Unless you are tough and strong and uncompromising, you are going to be eaten up. I think Dowell’s problem is that he was not given the weapons to fight the Opera House against the ludicrous Board and the abominable history of ballet taking second place to opera, and also that he was unable to fight for the thing that was central, which included really serious musical direction and really serious choreographic endeavour.

Nureyev was a fascinating dancer who proved to be a very great artistic director. What I loved and respected, despite some of the things he did as a dancer, was his profound and consuming passion for classical ballet

Where do you think a good dancer has proved an equally distinguished director?

George Balanchine actually, he was a very good dancer. Serge Lifar was a very, very fine director. He was like Nureyev, in that he made the Paris Opéra great. Then when he left in 1958, for the next 25 years the company was in the doldrums. Then along comes Nureyev, who was a fascinating dancer and proved to be a very great artistic director who, through the passion and glamour of his temperament, gave back to the Paris Opéra what it had long lacked, drive, force, a new repertory, and taught those miraculous dancers to be proud of themselves once again.

Was he a better director than dancer?

It’s a very interesting question. I think he actually was an inspired artistic director. What I loved and respected, despite some of the things he did as a dancer, was his profound and consuming passion for classical ballet. If there was one thing that mattered, it was a fifth position. And he was a very interesting case of a self-educated musical man who actually ended up, I think, being a very musical choreographer. His Raymonda has some extraordinary things in it.

Looking around at the very many distinguished dancers who are now coming to the end of their careers, are there any who you think have any chance of being a good artistic director?

I think it’s probably like riding a bicycle - you can’t know until you’re in the saddle. I think there are an awful lot who want to be artistic directors and who shouldn’t.

Going back to music, I was dismayed when I saw on a poll of fans on the ballet website, about which factors influenced their appreciation of a ballet work - choreography, music, visual, and so on - and a very very low rating of importance was given to music, something like 20 percent. I was horrified that so few ballet fans are musical.

I think it’s partly that they’ve had so much lousy dance and music to hear. They’ve been forced to watch and listen to rubbish. I find it extraordinary, also, that musical performances are so poor at the Opera House – I really don’t know how people can dance to such playing sometimes. Choreographers listen to music, endlessly, and it enters their souls, and out of it comes steps – this happened with Balanchine, Ashton, and with MacMillan. For a lovely piece called Symphony Kenneth listened to the Shostakovich first symphony day and night. Nowadays it is not possible to make steps to a score like John Adams or Philip Glass, unless you are Jerome Robbins, because the music does nothing – it just churns on, and you can’t just have steps churning on.

How far did your own musical training go?

I was a good pianist, till at 15 or 16 I realised that I wasn’t a good pianist and I was not prepared to practise seriously or hard enough.

You were born in Romford, I believe? An Essex boy.

I suppose, yes, I am an Essex boy. My father worked in the city, my mother was a wife and mother. I was the only child. My mother was born in 1895, at which time Romford was actually country, and they had horses, not cars. My mother had diphtheria when she was five, and she remembers how they had to lay straw in the street outside her house, because of the noise of the carriage wheels. My father remembers fields all around that house. It is now an Essex waste.

I studied French in Bordeaux and then at Oxford. For a while I worked in the city, for a friend of my father’s – some sort of import and export. I sat at a desk and papers came and went, and I occasionally had to go and look at wood coming in at the docks. And all this wood had little marks on its end, and your wood had some mark or other. I think my father had a terrible bust-up with his business partner, so I thought I’d got to earn my living somehow, and so I taught French for seven or eight years in a comprehensive in Dulwich, South London. I was enormously successful as a teacher, because I scared the living daylights out of the pupils.

Just by being thoroughly menacing. I believed they had to do what I told them, and I made them do so. I taught them very well and they were all very successful and passed their O-levels and their A-levels. I don’t have any temper, of course, I am the soul of sweetness and light. One or two of them still write to me occasionally. Eventually I was doing a lot of reviewing, and I got bored of the shlep to the school, and I’ve been writing full-time for 35 years now.

- Clement Crisp OBE, born 21 September 1926, died 1 March 2022

Add comment