There's a tension in Alfred Hitchcock’s early films between misogyny and condemnation of the patriarchal suppression of women. The suppression was inherent in the original sources from which The Pleasure Garden (1926), Easy Virtue (1927), Champagne (1928), The Manxman (1929), Blackmail (1929), Juno and the Paycock (1930), and The Skin Game (1931) were adapted.

Unconscious or not, the gynophobia that also flickers in these films is shared by The Lodger (1926), Downhill (1927), and Rich and Strange (1931). That it's intensified in Hitchcock's mature work, culminating in Psycho (1960) and Frenzy (1972), indicates the consistency with which the master of suspense sought to punish desirable and especially sexually active women.

Unconscious or not, the gynophobia that also flickers in these films is shared by The Lodger (1926), Downhill (1927), and Rich and Strange (1931). That it's intensified in Hitchcock's mature work, culminating in Psycho (1960) and Frenzy (1972), indicates the consistency with which the master of suspense sought to punish desirable and especially sexually active women.

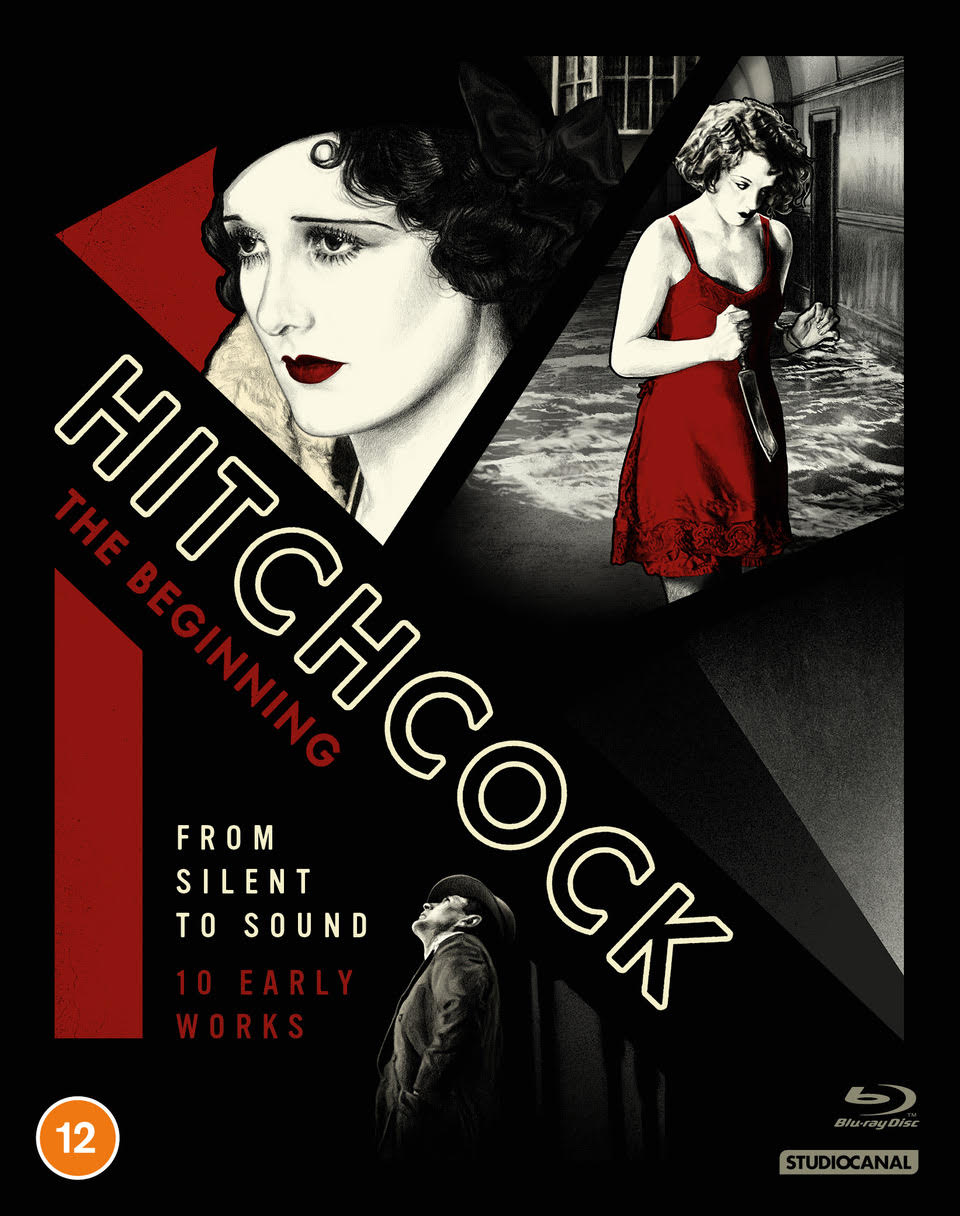

The Lodger, Downhill, and Easy Virtue are missing from StudioCanal’s 11-disc Blu-ray box set Hitchcock –The Beginning, but the films it assembles amply demonstrate their conflicted sexual politics. The set's subtitle From Silent to Sound acknowledges the technical transition Hitchcock made with more flair and inventiveness than his British peers.

Of his nine surviving silents, which were restored by the BFI and shown in 2012’s international touring exhibition, the collection includes The Ring (1927), Champagne, The Farmer’s Wife (1928), and The Manxman, along with the silent and sound versions of Blackmail and the talkies Murder! (1930), Juno and the Paycock, Rich and Strange, The Skin Game, and Number Seventeen (1932). The Murder! disc includes the simultaneously filmed German-language version, Mary (1931).

The addition to the set of Laurent Bouzereau’s 2024 documentary Hitchcock – The Legacy of Blackmail contextualises this pivotal phase in his career, during which he sharpened his skill in manipulating images to create emotional effects, harnessed sound to the same end, and indulged the obsessions and developed the ideas that define his oeuvre.

The documentary avails itself of a paradigmatic sequence with which Hitchcock plays on the agonizing guilt of Blackmail’s Alice White (Anny Ondra). The morning after she has stabbed to death an artist (Cyril Ritchard) who was about to rape her in his studio, she sits at her family's breakfast table with a glazed expression. The repetition of the word "knife" by a visiting neighbour (Phyllis Monkman), who's gossiping about the murder, causes Alice to shock herself by mishandling a bread knife. Hitchcock had had the bread knife shone until it gleamed and winked, and he instructed his sound editor to mix down the neighbour's chatter except for the one incriminating word. The double impact is startling.

English Hitchcock (1999), Charles Barr’s authoritative study of the director’s pre-Hollywood films, debunks the notion that he was the sole creator of them. Barr’s analysis shows how dependent Hitchcock was on their source novels, plays, and stories, and the vital contributions of the screenwriters Eliot Stannard and Charles Bennett. (Pictured below: Hitchcock and Anny Ondra get used to sound on the set of Blackmail)

It became Hitchcock’s practise to cast an attractive actress – Betty Balfour in Champagne, Ondra in Blackmail and The Manxman, Isabel Jeans in Easy Virtue – and torment her character psychologically. He favoured the menacing of blondes, of course, but dark-haired women – Kathleen O'Regan in Juno and the Paycock, Phyllis Konstam in The Skin Game – weren't exempt from his retributive or murderous gaze.

It became Hitchcock’s practise to cast an attractive actress – Betty Balfour in Champagne, Ondra in Blackmail and The Manxman, Isabel Jeans in Easy Virtue – and torment her character psychologically. He favoured the menacing of blondes, of course, but dark-haired women – Kathleen O'Regan in Juno and the Paycock, Phyllis Konstam in The Skin Game – weren't exempt from his retributive or murderous gaze.

Champagne, adapted by Hitchcock and Stannard from a Walter C. Mycroft story, predated screwball comedy; Hitchcock described it as “probably the lowest ebb in my output." As slight as the film is, it harbours a disturbing Electra complex fantasy. That Balfour’s nightclub worker imagines rather than experiences a sexual assault on her by her father’s predatory-seeming watchdog (Theo van Alten) does not lessen her fear of the man or soften its effect on the viewer.

In The Manxman, Hitchcock relished the romantic agony of Ondra’s barmaid Kate. Set in the Isle of Man’s fishing community (though filmed mostly on Cornwall locations), the movie fleetingly echoes John Grierson’s herring industry documentary Drifters (also 1929) but segues quickly into a spare love-triangle melodrama that probes – and chastises – female desire.

The daughter of a repressive fisherman turned publican, Kate is loved by two men, the handsome, cheerful, and penniless fisherman Pete (Carl Brisson) and the stolid and more melancholy Philip (Malcolm Keen), an upcoming lawyer and future judge.

Aggressively wooed by Pete, Kate agrees to marry him, but falls in love with Philip in the isle’s sun-dappled countryside while Pete is overseas making money. For Kate, the man of power and substance is more alluring than the poorer man. Though Hitchcock gets close here to the Darwinian core of pre-feminist sexual politics, the film’s moralistic tone originated in Hall Caine’s 1894 novel, which Stannard had adapted. (Pictured below: Phyllis Konstam and Edward Chapman in The Skin Game)

After reluctantly marrying Pete, Kate has a baby whose paternity is in doubt. She spirals into a state of sexual anguish that borders on the holy. Hitchcock's camera savours her exquisite pain and the rapt sensuality of the actress who plays her – as it would later savour the trials of Joan Fontaine, Grace Kelly, Kim Novak, and Tippi Hedren. By 1929, Hitchcock's gazing on so much unavailable blonde beauty had become a sadomasochistic fetish. He said The Manxman was “banal,” which couldn’t be further from the truth.

After reluctantly marrying Pete, Kate has a baby whose paternity is in doubt. She spirals into a state of sexual anguish that borders on the holy. Hitchcock's camera savours her exquisite pain and the rapt sensuality of the actress who plays her – as it would later savour the trials of Joan Fontaine, Grace Kelly, Kim Novak, and Tippi Hedren. By 1929, Hitchcock's gazing on so much unavailable blonde beauty had become a sadomasochistic fetish. He said The Manxman was “banal,” which couldn’t be further from the truth.

Like Easy Virtue (adapted by Stannard from the Noel Coward play), The Skin Game traces a wealthy family’s repudiation of a woman with a compromised past who has married into it. Adapted by Hitchcock and his scenarist wife Alma Reville from John Galsworthy’s play, the film centres on a land feud between the upper-class Hillcrists and the nouveau riche family of the grasping industrialist Hornblower (Edmund Gwenn).

The Hillcrists learn they can prevail over their neighbours by threatening to expose Chloe (Phyllis Konstam), the pregnant wife of Charles Hornblower (John Longden), who once worked as a law firm’s correspondent (guaranteeing proof of errant husbands’ adultery) in divorce cases. Whereas Galsworthy has his Chloe survive her attempt to drown herself, Hitchcock allows her film equivalent no reprieve. (Pictured below: Sara Allgood and Kathleen O'Regan in Juno and the Paycock)

Only Blackmail and The Manxman among the films in the box set suggest Hitchcock would become a master, but most of them show him experimenting and refining his craft as he readied himself for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), The Lady Vanishes (1938), and success in the Hollywood studio system. His fixations, phobias, and neuroses hardened simultaneously.

Only Blackmail and The Manxman among the films in the box set suggest Hitchcock would become a master, but most of them show him experimenting and refining his craft as he readied himself for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), The 39 Steps (1935), The Lady Vanishes (1938), and success in the Hollywood studio system. His fixations, phobias, and neuroses hardened simultaneously.

Recent or newly restored films in the box set include both versions of Blackmail, Rich and Strange, and Number Seventeen. The Skin Game and Juno and the Paycock (making its Blu-ray debut) have been remastered in HD. There are new and alternative scores, audio excerpts from Hitchcock’s celebrated discussions of his films with François Truffaut; audio commentaries; and three contributions from Barr.

Add comment