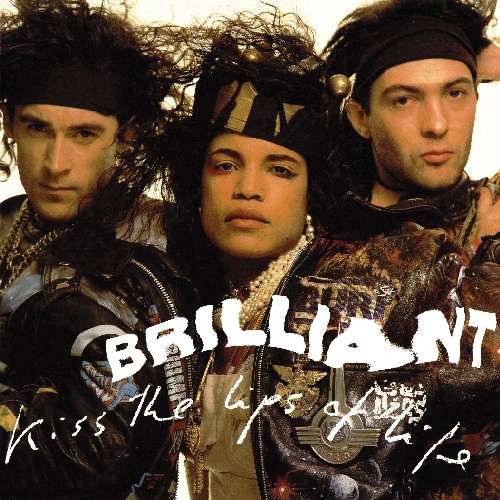

Youth, AKA Martin Glover (b 1960), is a renowned music producer and bassist in the post-punk band Killing Joke. He achieved his first success with the latter in the late Seventies and has often been at the forefront of innovation and development in British music since. Having played a key role in developing their uniquely dubby, dark sound, Youth parted ways with Killing Joke in 1982 and formed Brilliant, a band that espoused an ahead-of-its-time dance musical ethos and included the involvement of both future members of the KLF.

When the musical revolution of acid house hit the UK in 1988, Youth was all over it like a rash, DJing in the first ever chillout lounge at Land of Oz, and involved with the nascent KLF and The Orb, as well as achieving hits via his involvement with crossover acts Zoe (“Sunshine on a Rainy Day”) and Blue Pearl (“Naked in the Rain”). His series of labels, WAU! Mr Modo, Butterfly, Dragonfly, Liquid Sound Design etc, have been influential in dance music, notably in the creation of the psychedelic trance scene, but he has achieved greater renown via his production on multitudes of records, including major albums by The Verve, Embrace and Beth Orton. He has also recorded three albums with Paul McCartney as The Fireman and was recently awarded the PPL Outstanding Contribution to UK Music at the MPG Awards 2016.

We meet at his house near Wandsworth Common where, dressed down in green and black, with his trademark muss of hair now grey but still poking out everywhere, he sits in swivel chair at his desk in a large high-ceilinged room overflowing with knick-knacks and oddments from his life. The overarching tone of the space is one of free-flowing eccentricity mingled with Eastern spirituality. Ambient music plays quietly, interspersed with occasional moments of David Bowie. Youth chain smokes, not always cigarettes, and chats in the most easy-going, open and unpretentious manner.

THOMAS H GREEN: When you were awarded the PPL Outstanding Contribution to UK Music at the MPG Awards back in February, you put together a rather special band to headline the event at Park Lane's Grosvenor House Hotel – Alex Paterson of The Orb, Richard Ashcroft, Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols, Mark Stewart of the Pop Group, Jah Wobble and Pink Floyd sidesman Guy Pratt. What was that like?

YOUTH: Intense! Even though a lot of those cats were outsiders, they all know their chops. The stressful part was putting the line-up together and having to ask people – big asks – but everyone agreed. I was really amazed and honoured.

YOUTH: Intense! Even though a lot of those cats were outsiders, they all know their chops. The stressful part was putting the line-up together and having to ask people – big asks – but everyone agreed. I was really amazed and honoured.

What play did you play?

I played a Fender 6 which is actually a bass but with six strings, like a guitar tuned down an octave, as favoured by Brian Wilson, with a Fifties twang, quite Hank Marvin. I had two other bass players in Guy Pratt and Jah Wobble. I didn’t want to have to worry about carrying the rhythm – I focused on having fun.

What songs did you play?

“Bittersweet Symphony”, “The Drugs Don’t Work”, “Little Fluffy Clouds”, “Sunshine on a Rainy Day", Killing Joke’s “Pssyche”, going back to where it began with Mark Stewart [on vocals]. That one sounds most current in a weird way, so ahead of its time, a good way to finish. We finish Killing Joke shows with it – it’s so fast, it covers a lot of things I’ve been involved with, fusing disco, rock, dub, and also I sing a verse so I get up front. A great finale.

What is your earliest memory?

That’s a really good question. I’ve never been asked that. I have a vivid memory when I was a baby of being in my grandmother’s 1950s pram, being pushed round a park in Solihull, Birmingham. My grandmother lived in this Victorian terraced house. She was one of 13 kids, very working-class, a single mum. My auntie and uncle still lived at the house into their fifties. She was quite a matriarch, didn’t let them go easy. She had a lodger for 30 years who was her secret lover, an outdoor toilet, and a mangle in the back. When my mum and dad first had me and my sister, they were living in a council flat working full time. They were in London. My dad’s from Wales but grew up in Birmingham with his mum so for the first two years of my life I spent a lot of time up there with my grandma, a surrogate parent really, I remember the smell of piss and disinfectant because they had an outdoor toilet and chamber potties under the beds. I’d get into bed at night, look out of the window and see a guy come along the road with his ladder to light the gas lights in the street. They still had them in the early Sixties. I caught the end of an era. (Youth pictured below)

My granny still had a mangle in the Seventies. I hadn’t thought about that in years. Mangles really were from another era.

I moved down south aged two or three, when my mum and dad got a big enough flat. We were living just outside Slough, then near Gerrards Cross, the village of Stoke Poges in the countryside. When we were in Slough they were building it, one big building site. At my second primary school we’d bunk off at lunch to play in this big building site. The other great thing about Slough was it had a great cinema, and right over the road was a joke shop run by Tommy Cooper’s twin brother. He wore a fez in the shop. That’s where we’d buy our pranks. My parents split when I was about nine. Dad moved to London, Mum moved to Reading and hooked up with my stepfather pretty quick. I was ping-ponging between the two, then my mum and stepfather moved to Paddington. I started going to secondary school in Kilburn, then my Dad moved round here. When my dad got really ill about 20 years ago, he was given six months to live. I thought I’d better hang out with him a bit so I said, “Find me a place round here.” He found me this house. He was a builder as well so he helped do it up. But then he carried on living for another 15 years. Amazing! That was great. By the time he died we were very close.

I moved down south aged two or three, when my mum and dad got a big enough flat. We were living just outside Slough, then near Gerrards Cross, the village of Stoke Poges in the countryside. When we were in Slough they were building it, one big building site. At my second primary school we’d bunk off at lunch to play in this big building site. The other great thing about Slough was it had a great cinema, and right over the road was a joke shop run by Tommy Cooper’s twin brother. He wore a fez in the shop. That’s where we’d buy our pranks. My parents split when I was about nine. Dad moved to London, Mum moved to Reading and hooked up with my stepfather pretty quick. I was ping-ponging between the two, then my mum and stepfather moved to Paddington. I started going to secondary school in Kilburn, then my Dad moved round here. When my dad got really ill about 20 years ago, he was given six months to live. I thought I’d better hang out with him a bit so I said, “Find me a place round here.” He found me this house. He was a builder as well so he helped do it up. But then he carried on living for another 15 years. Amazing! That was great. By the time he died we were very close.

Did you inherit his building skills?

I’m terrible with DIY. I do it but I get impatient and bodge it. However, it is similar to constructing music. I can see the parallels with being a builder because my dad would be organising teams of people, schedules, budgets, deliveries. He was an artist too, a great painter. I inherited that from him. I paint a lot, I’m quite tactile with my hands, but anything mathematical and precise, like a nail and hammer, well, I’m quite clumsy. I generally make it worse than it was.

Flipping the coin of the subject, in 1983 you produced the debut album by Alien Sex Fiend, Who’s Been Sleeping In My Brain?. What was that like?

They were the first band to commission me to produce them.

Does Nik Fiend [pictured below right] wear his corpse face paint all the time?

I haven’t seen him for 30 years. He didn’t wear it all the time… most of the time. There was an interesting shift, coming out of punk, going into post-punk, new romantics, Blitz Kids, then the Batcave suddenly popped up, took on where [London club] Billy’s left off. Billy’s was a Thursday night Bowie club that started to define the new romantic look and the goth look at same time. Studio 21 as well. Depeche Mode went one way, Visage and Steve Strange took it another way, [Specimen singer] Olli [Wisdom] took it another way with the Batcave, catering for the Siouxsie Sioux look. Even though the Batcave was the seminal, archetypal goth club it catered to a broad range. People went to the Blitz but went to the Batcave as well. Boy George went down the Batcave. It was important because punk-related clubs before the Batcave were all band-orientated. You’d have three bands on. The Batcave was more about the DJ and it was also later at night, on until 2am. They might have one band do a short set but it was all about the dancefloor. They’d play Soft Cell and Depeche Mode but it was also quite rock-orientated, Hamish [McDonald] from Sexbeat was the DJ and he was very good in how he picked the tunes. There’d be a Banshees one, The Cure, but then it would start to go more electronic, things like Portion Control, proto-industrial, another band I produced. It gave me ideas. I realised we’ve got to start making records that fit with this dancefloor and [Alien Sex Fiend’s debut single] “Ignore the Machine” was perfect because they had this drum machine. It gave a four-to-the-floor beat, this pulse, then they jammed guitar and vocals on top. All I did was dub it up. It immediately became a dancefloor hit and set the pace for rest of the album.

I haven’t seen him for 30 years. He didn’t wear it all the time… most of the time. There was an interesting shift, coming out of punk, going into post-punk, new romantics, Blitz Kids, then the Batcave suddenly popped up, took on where [London club] Billy’s left off. Billy’s was a Thursday night Bowie club that started to define the new romantic look and the goth look at same time. Studio 21 as well. Depeche Mode went one way, Visage and Steve Strange took it another way, [Specimen singer] Olli [Wisdom] took it another way with the Batcave, catering for the Siouxsie Sioux look. Even though the Batcave was the seminal, archetypal goth club it catered to a broad range. People went to the Blitz but went to the Batcave as well. Boy George went down the Batcave. It was important because punk-related clubs before the Batcave were all band-orientated. You’d have three bands on. The Batcave was more about the DJ and it was also later at night, on until 2am. They might have one band do a short set but it was all about the dancefloor. They’d play Soft Cell and Depeche Mode but it was also quite rock-orientated, Hamish [McDonald] from Sexbeat was the DJ and he was very good in how he picked the tunes. There’d be a Banshees one, The Cure, but then it would start to go more electronic, things like Portion Control, proto-industrial, another band I produced. It gave me ideas. I realised we’ve got to start making records that fit with this dancefloor and [Alien Sex Fiend’s debut single] “Ignore the Machine” was perfect because they had this drum machine. It gave a four-to-the-floor beat, this pulse, then they jammed guitar and vocals on top. All I did was dub it up. It immediately became a dancefloor hit and set the pace for rest of the album.

Is it true you’re currently working on a project with Al Comet from [Swiss industrial rockers] the Young Gods?

Jaz [Coleman, the singer] from Killing Joke [pictured left] put me in touch with Al. He left the Young Gods about five years ago and it coincided with his marriage breaking down. He did the classic thing of going to India. He decided to stay in Benares and study sitar. He did that for four or five years – he’s got a guru-teacher there. He started to develop playing sitar with guitar pedals. He came to me with this sitar album – quite ambient – and asked if I’d be interested in mixing it up. I thought I might put it out on my label Liquid Sound Design, which is more for the Ibiza/Goa chill-out crew. I started mixing it with that in mind. Then I took him to see Michael Rother from NEU! last Friday and of course that was really inspiring. The Young Gods came out of that kosmische German scene, more Eighties but informed by the same criteria and aesthetic. Michael Rother has these really tight bass sequences, those harmonic peaks even made me think of Big Country at times. He does it with such an economy of notes. We both realised, after that gig, that Al's new music should be more for that audience, maybe not for my label, a U-turn turn.

Jaz [Coleman, the singer] from Killing Joke [pictured left] put me in touch with Al. He left the Young Gods about five years ago and it coincided with his marriage breaking down. He did the classic thing of going to India. He decided to stay in Benares and study sitar. He did that for four or five years – he’s got a guru-teacher there. He started to develop playing sitar with guitar pedals. He came to me with this sitar album – quite ambient – and asked if I’d be interested in mixing it up. I thought I might put it out on my label Liquid Sound Design, which is more for the Ibiza/Goa chill-out crew. I started mixing it with that in mind. Then I took him to see Michael Rother from NEU! last Friday and of course that was really inspiring. The Young Gods came out of that kosmische German scene, more Eighties but informed by the same criteria and aesthetic. Michael Rother has these really tight bass sequences, those harmonic peaks even made me think of Big Country at times. He does it with such an economy of notes. We both realised, after that gig, that Al's new music should be more for that audience, maybe not for my label, a U-turn turn.

I was thinning down my record collection a bit, selling off some Nineties dance vinyl and I made quite a bit of money recently selling an old Goa trance 12” single on your Dragonfly label – The Pleiadians’ “Alycone” from 1997. I got £200 for it. Why do you think it sold for that kind of money?

Because I did a good job of the label, the way it was curated. It was pioneering, the first Goa trance label. It was very, very difficult to get a release on Dragonfly. I’d tell artists to go back and remix and remix until it was perfect. I did it for seven or eight years and the scene was changing so then I stopped. We have this perfect legacy of about 50 albums and 100 12”s, all quite limited to under 500 copies, very collectable and still influential on the psy-trance scene. I wish I had a few boxes up in the loft!

Who chose Nick Launay to produce the second Killing Joke album, What's THIS for...!?

Well, he didn’t produce it, we did, although he’s a very well-established producer now [recent productions include Arcade Fire and Nick Cave]. We wanted Hugh Padgham. He did “Follow the Leaders", then he got called onto some Phil Collins album or something, but he came back to mix it with us. I mixed it with him in 48 hours on LSD. For the first album we went to Marquee Studios with the in-house engineer Phil Harding, who’s great and ended up being one of PWL’s big mixers. That was just chance, whereas the second album, we plotted it. Nick Launay was in-house at Townhouse. He hadn’t really done anything but Hugh recommended him. We’d also had an argument that involved a bit of a pizza fight so I think Phil was quite happy to make his excuses and leave. I think he might have done some sessions with Kate Bush for the Army Dreamers album and that maybe swung it for us. That was the reason we went to Townhouse, because she used the stone drum room in there, the same studio Phil Collins used for “In the Air Tonight”. Not long after that, because she was a Killing Joke fan, she asked me to play bass on The Hounds of Love, which was a great honour. Nick managed to ride through the whole process well. I do remember we had a birthday cake which had a lot of hashish in and he didn’t realise and took a slice. It was the middle of the afternoon but two hours later he disappeared. We asked at reception and they said he’d wobbled off on his bicycle about half an hour ago. We didn’t see him for two days. Luckily he forgave us. He came back and we finished the record. It’s one of my favourite Killing Joke albums. We learned a lot from Nick and Hugh.

Well, he didn’t produce it, we did, although he’s a very well-established producer now [recent productions include Arcade Fire and Nick Cave]. We wanted Hugh Padgham. He did “Follow the Leaders", then he got called onto some Phil Collins album or something, but he came back to mix it with us. I mixed it with him in 48 hours on LSD. For the first album we went to Marquee Studios with the in-house engineer Phil Harding, who’s great and ended up being one of PWL’s big mixers. That was just chance, whereas the second album, we plotted it. Nick Launay was in-house at Townhouse. He hadn’t really done anything but Hugh recommended him. We’d also had an argument that involved a bit of a pizza fight so I think Phil was quite happy to make his excuses and leave. I think he might have done some sessions with Kate Bush for the Army Dreamers album and that maybe swung it for us. That was the reason we went to Townhouse, because she used the stone drum room in there, the same studio Phil Collins used for “In the Air Tonight”. Not long after that, because she was a Killing Joke fan, she asked me to play bass on The Hounds of Love, which was a great honour. Nick managed to ride through the whole process well. I do remember we had a birthday cake which had a lot of hashish in and he didn’t realise and took a slice. It was the middle of the afternoon but two hours later he disappeared. We asked at reception and they said he’d wobbled off on his bicycle about half an hour ago. We didn’t see him for two days. Luckily he forgave us. He came back and we finished the record. It’s one of my favourite Killing Joke albums. We learned a lot from Nick and Hugh.

Blue Pearl is a strange name for a group.

[Blue Pearl singer] Durga McBroom [pictured left] grew up in LA and her ethnicity is African-American, but her parents were very progressive. Her father was one of the first black doctors in Hollywood in the Fifties, a significant pioneering professional. They were devotees of this Hindu guru. Blue Pearl is a metaphor for a state of enlightenment in a particular meditation, where you see the blue pearl.

[Blue Pearl singer] Durga McBroom [pictured left] grew up in LA and her ethnicity is African-American, but her parents were very progressive. Her father was one of the first black doctors in Hollywood in the Fifties, a significant pioneering professional. They were devotees of this Hindu guru. Blue Pearl is a metaphor for a state of enlightenment in a particular meditation, where you see the blue pearl.

When rave culture arrived, it was rapt with euphoria and fluffy positivity – did you see it as inverse to punk’s harsher, more critical values?

Killing Joke were quite radical. We came up after punk, doing things punk bands didn’t do – disco rhythms and dub basslines. The Clash did a little, but not in ’78-‘79 when we came along, and not as far as we took it. I came into punk from being a soul boy which was all about disco and funk. It was all about going to [London clubs] Crackers and Global Village and the Lacy Lady. When I was 14-15 that was the proto-punk scene in London for teenagers. A lot of the early punks were soul boys – the whole jelly sandals, Bowie pegs thing was from soul boys. By 1975 they were playing 12”s in these clubs. The soul boy scene is not very well documented but it’s very important. It had an influence on us in Killing Joke. The big influence just prior to acid house was hip hop and electro coming out of New York. Drum machines were starting to be used in indie productions – 23 Skiddoo, 400 Blows, all that became the beginnings of acid house, the indie-dance side of it. [DJ] Alfredo in Ibiza would play Thrashing Doves, early new beat, Nitzer Ebb even. Brilliant were really trying to emulate [the DJ] Tony Humphries' live New York radio mixes on WBLS and KTU, mashing stuff up. Brilliant tried to do that with two drummers and two basses. Acid house quickly filtered through to a lot of prime movers of punk. They came to the early Boys Own parties. At [DJ Paul Oakenfold’s seminal club night] Land of Oz, the first chill out room is credited to [future Orb producer] Alex Paterson, myself and [future KLF producer] Jimmy Cauty.

Tell us about Land of Oz.

It was at Heaven. I’d gone there at 14 when it was Global Village.

How did you get into these clubs at 14?

They didn’t have ID and if you looked 17, they weren’t too fussed. At Land of Oz they had a back room bar where a guy called Roger the Hippy played hippy records – Gong and stuff. We thought was incongruous but radical as well, then Oakey asked if we’d like to do it because Roger was going away for a few months. [DJ-producer Andrew] Weatherall was living above me and Alex Paterson in Battersea. We all knew each other. Oakey would come over. He said, “Play records you’d like to play at home”. Everyone was taking so much ecstasy you needed a space to chill out. He was the first to recognise that, so we brought in three or four decks and played ambient sound effects, slipping in the occasional Marshall Jefferson Chicago beat. It certainly gave us our start to navigate into the early KLF stuff.

When did you first come across ecstasy?

It was 1986, before acid house. I was seeing a girl called Josie Jones, gorgeous, a figure on the scene, a real funny spark from Liverpool. She’d been in Peter Wylie’s band Wah! Heat. Sadly she died last year. She had a great life – everybody loved her. She was good mates with all the Liverpool artists and she said, “Do you want to come to a party at [Frankie Goes To Hollywood member] Paul Rutherford’s tonight? We’re going to try a new drug. It’s called ecstasy.” So I drove her up there, no idea what to expect, get up to this penthouse flat he’d got in Wapping, right outside The Sun’s newspaper’s new factory. It was when strikers were picketing and we had to drive past riot police on horses and pickets to get there. He was in this modern Canary Wharf-type flat. The place was full of faces and names, George Michael was there, quite a camp scene, a lot of gay friends, all of us probably doing this for the first time and we didn’t know what to expect. Paul had a really big Persian rug and he said, “We’re going to turn this into a magic carpet, and everyone’s got to get into fancy dress.” He had this huge room full of fancy dress. Everybody piled in and got dressed up, then the E started kicking in. I remember being floppy, lying down having Josie and June [Montana, of Brilliant] body paint my legs, a really chilled-out, wonderful trip. A couple of years later I met Nancy Noise. She introduced me to [London’s original acid house mecca] Shoom. She said, “Come down, everybody gets on the E and dances all night – you’ll love it.” I said, “You can’t dance on E – you’ve got to lie down and have somebody body paint you.” She goes, “No, they all get up and dance.” I was saying, “There’s no way.” I went down and – wow! – yes, you can dance on Ecstasy.

It was 1986, before acid house. I was seeing a girl called Josie Jones, gorgeous, a figure on the scene, a real funny spark from Liverpool. She’d been in Peter Wylie’s band Wah! Heat. Sadly she died last year. She had a great life – everybody loved her. She was good mates with all the Liverpool artists and she said, “Do you want to come to a party at [Frankie Goes To Hollywood member] Paul Rutherford’s tonight? We’re going to try a new drug. It’s called ecstasy.” So I drove her up there, no idea what to expect, get up to this penthouse flat he’d got in Wapping, right outside The Sun’s newspaper’s new factory. It was when strikers were picketing and we had to drive past riot police on horses and pickets to get there. He was in this modern Canary Wharf-type flat. The place was full of faces and names, George Michael was there, quite a camp scene, a lot of gay friends, all of us probably doing this for the first time and we didn’t know what to expect. Paul had a really big Persian rug and he said, “We’re going to turn this into a magic carpet, and everyone’s got to get into fancy dress.” He had this huge room full of fancy dress. Everybody piled in and got dressed up, then the E started kicking in. I remember being floppy, lying down having Josie and June [Montana, of Brilliant] body paint my legs, a really chilled-out, wonderful trip. A couple of years later I met Nancy Noise. She introduced me to [London’s original acid house mecca] Shoom. She said, “Come down, everybody gets on the E and dances all night – you’ll love it.” I said, “You can’t dance on E – you’ve got to lie down and have somebody body paint you.” She goes, “No, they all get up and dance.” I was saying, “There’s no way.” I went down and – wow! – yes, you can dance on Ecstasy.

Whatever became of June Montana?

After Brilliant [pictured left] collapsed she did Disco 2000 with Jimmy [Cauty] and [his wife] Cressida. Then she had a solo deal with George Michael. He loved her and got her to sign to his label, but nothing really happened. So she ended up becoming one of the top door bitches in clubland, with the guest list. Last time I saw her she was doing Chinawhite’s. She does super-exclusive parties because she knows all those people. It’s a real waste of a great voice, but that’s what she was doing when we first met her, always working the door on clubs. We thought she was going to be the next Sade.

After Brilliant [pictured left] collapsed she did Disco 2000 with Jimmy [Cauty] and [his wife] Cressida. Then she had a solo deal with George Michael. He loved her and got her to sign to his label, but nothing really happened. So she ended up becoming one of the top door bitches in clubland, with the guest list. Last time I saw her she was doing Chinawhite’s. She does super-exclusive parties because she knows all those people. It’s a real waste of a great voice, but that’s what she was doing when we first met her, always working the door on clubs. We thought she was going to be the next Sade.

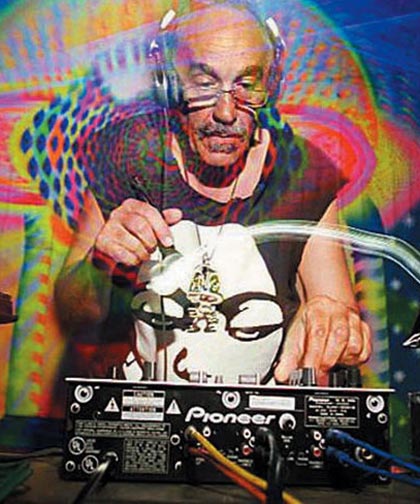

Do you know Raja Ram [pictured below right]? He’s been a major player on the psy-trance scene – and is a great interviewee.

Yeah, very well. I’ve been working with him over the past year producing an album of his flute music. Very ambient but not solo, quite different from [Ram’s roots music jam band] Shpongle. He’s in his late 70s, DJing around the world, playing with Shpongle around the world, an extraordinary character.

I spoke to him about writing his biography but eventually I think he decided to do it himself. I hope he does, he’s had an amazing life.

I’ve been encouraging him to do that for years. I think he’s in India right now doing some gigs in Goa. He was part of an Indian guru commune in London and that’s how he got the primary members of [Ram’s Seventies prog rock band] Quintessence together. He then auditioned 500 kids in Notting Hill to get the rest. They did two or three albums on Island. At their peak they sold out the Albert Hall. He felt it was his path to stop it then. It gives the work you’ve done a big resonance because you’re not exploiting or milking it. I understand why he did it but it was quite callous towards the rest of the band who were just getting used to being stars. There was a great piece on Quintessence recently in Record Collector. There’s a picture of him smiling and all the rest of the band looking like this [pulls moody face]. The caption was “Everything’s great, you’re all sacked”. He then went into the wine business for a long time, but he never stopped playing the flute. He was a really inspirational figure in the early Goa trance days.

I’ve been encouraging him to do that for years. I think he’s in India right now doing some gigs in Goa. He was part of an Indian guru commune in London and that’s how he got the primary members of [Ram’s Seventies prog rock band] Quintessence together. He then auditioned 500 kids in Notting Hill to get the rest. They did two or three albums on Island. At their peak they sold out the Albert Hall. He felt it was his path to stop it then. It gives the work you’ve done a big resonance because you’re not exploiting or milking it. I understand why he did it but it was quite callous towards the rest of the band who were just getting used to being stars. There was a great piece on Quintessence recently in Record Collector. There’s a picture of him smiling and all the rest of the band looking like this [pulls moody face]. The caption was “Everything’s great, you’re all sacked”. He then went into the wine business for a long time, but he never stopped playing the flute. He was a really inspirational figure in the early Goa trance days.

Was he there with you at the start?

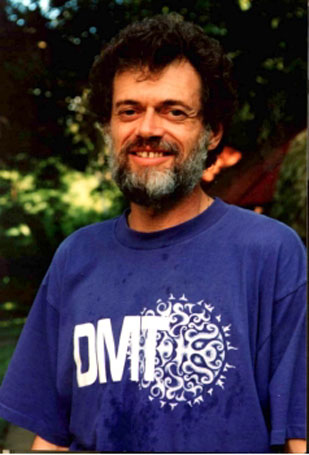

There’s a great story. I had [cosmic botanist, author and psychedelic raconteur] Terrence McKenna [pictured left] over to an event at my studios in Brixton. I used to get inspirational figures over to give a talk and we’d have a party out in the garden. [Synthesizer genius] Bob Moog did it one year. I had some really cool cats over and McKenna was one of the coolest. Afterwards he gave Raja some of this legendary pink DMT. Later me and Raj and three other people, including [British LSD evangelist] Brian Barritt, who was an associate of Timothy Leary’s. He’d never done DMT so I invited him, did it in a ceremony in the back of my garden. The story goes that out of that ceremony me and Raj invented psychedelic trance. Which in a way isn’t too far off the truth.

There’s a great story. I had [cosmic botanist, author and psychedelic raconteur] Terrence McKenna [pictured left] over to an event at my studios in Brixton. I used to get inspirational figures over to give a talk and we’d have a party out in the garden. [Synthesizer genius] Bob Moog did it one year. I had some really cool cats over and McKenna was one of the coolest. Afterwards he gave Raja some of this legendary pink DMT. Later me and Raj and three other people, including [British LSD evangelist] Brian Barritt, who was an associate of Timothy Leary’s. He’d never done DMT so I invited him, did it in a ceremony in the back of my garden. The story goes that out of that ceremony me and Raj invented psychedelic trance. Which in a way isn’t too far off the truth.

It’s a good story…

Obviously other people were doing stuff. Early prime movers of Goa trance were ex-members of Brilliant, Ben Watkins, who became Juno Reactor, and Stephane Holweck, who’d been in French experimental band Magma. They did a track in 1987 called “Sonar” that I put out on my label with Alex Paterson, WAH! Mr Modo. People cite it as the first made-for-Goa record. It was renamed “Anjuna Dawn”. But there were so many people involved in that sound and how it came about. All the artists who’d I’d signed in the first wave splintered off and set up their own labels. The whole thing exploded so we only had it for a year or two where everyone was on [Youth’s pre-Dragonfly label] Butterfly.

However unprogressive psy-trance music the music sometimes is, the parties are great and I always admire how the scene survives completely off-radar. Shpongle, who don’t even get a mention in the music press, sold out the Roundhouse!

Shpongle have become the new Grateful Dead in America, selling out arenas like Red Rocks. My theory is that because there’s absolutely zero coverage of psychedelic trance, that ensured its survival. It never became hip so it could never sell out. It also facilitated an international bohemian travel lifestyle scene that’s become bigger and bigger.

The Fireman is a project with you and Paul McCartney. It appears to have started life as a remix project for McCartney’s 1993 album Off The Ground, so how did it become an actual recording band?

Yes, it started off as a remix commission for that album. I quickly suggested that rather than remix one track I go through all his album takes and construct a new track out of all the different sounds I found. He said, “Remix it but help yourself to any sounds off the album.”

How had he heard of you?

He’d read an interview with me in Q when I’d come back from India. I cited The Beatles as being a big influence on the burgeoning British dance scene. He rang me up out of the blue, got my number through my manager, who said, “Paul McCartney’s going to ring you in a bit – keep your phone on.” He rang and said, “Would you like to pick some sounds from the multi-tracks?” I went down there and said, “Look, I can’t really pick a track, but I love the sounds and I’ve started putting them together. Maybe we can add to that…” He said, “That’s interesting.” I was thinking maybe we could get him to do some overdubs and create something cooler. He brought Linda down. I said, “We need to get Linda to do some percussion.” He said, “Do you mind if we watch you doing the mixing?” I said, “Sure, do what you like.” Normally I wouldn’t have artists there if I was doing the mixes because they’d be anxious and precious – “Turn my vocal up!” – but he said, “I won’t get in the way.” They came in one night after a photographic show, quite late, and I was still at it. They stayed until six in the morning. I was doing all these mad mixes taking drums out, putting them back in again. He later took them away. I explained my intention was to make those mixes into one remix but he wanted to put them all out under another name. He said, “I don’t care, I love it – they sound great in the car.” So that was the first Fireman album [Strawberries Oceans Ships Forest]. Then I said, “It would be good if we did that with a view to making an album rather than lots of mixes.” That became the second Fireman album [Rushes, 1998]. We did that over a year. It was great fun because there wasn’t the pressure of making an album, just, let’s have fun, let’s experiment. Punk rock, for me, is always about experimentalism.

He’d read an interview with me in Q when I’d come back from India. I cited The Beatles as being a big influence on the burgeoning British dance scene. He rang me up out of the blue, got my number through my manager, who said, “Paul McCartney’s going to ring you in a bit – keep your phone on.” He rang and said, “Would you like to pick some sounds from the multi-tracks?” I went down there and said, “Look, I can’t really pick a track, but I love the sounds and I’ve started putting them together. Maybe we can add to that…” He said, “That’s interesting.” I was thinking maybe we could get him to do some overdubs and create something cooler. He brought Linda down. I said, “We need to get Linda to do some percussion.” He said, “Do you mind if we watch you doing the mixing?” I said, “Sure, do what you like.” Normally I wouldn’t have artists there if I was doing the mixes because they’d be anxious and precious – “Turn my vocal up!” – but he said, “I won’t get in the way.” They came in one night after a photographic show, quite late, and I was still at it. They stayed until six in the morning. I was doing all these mad mixes taking drums out, putting them back in again. He later took them away. I explained my intention was to make those mixes into one remix but he wanted to put them all out under another name. He said, “I don’t care, I love it – they sound great in the car.” So that was the first Fireman album [Strawberries Oceans Ships Forest]. Then I said, “It would be good if we did that with a view to making an album rather than lots of mixes.” That became the second Fireman album [Rushes, 1998]. We did that over a year. It was great fun because there wasn’t the pressure of making an album, just, let’s have fun, let’s experiment. Punk rock, for me, is always about experimentalism.

The third album by The Fireman [Electric Arguments, 2008] really went for it, had a little bit of a “Helter Skelter”, White Album thing going on in places…

I really pushed him to do more vocals. That was the challenge, to approach it the way we’ve done before but with songs. He said, “How are we going to do that, come in with a blank sheet every day?” I said, "We’ll use the artists’ approach, Burroughs' cut-up technique, bring in loads of poetry books, pick a line or word from each of these three poems, then we’ll throw them up and see what lines come out. You have to do the vocal in 20 minutes.” He liked that. At the same time I was learning so much from him about how to remain inspired. He’d been doing a symphony one day when he came in, next time I’d see him he’d be doing a poetry book. The next time he’d been doing some painting. I remember asking him if he ever got bored and he said, “Hmmm… no.” He really utilises his time and really appreciates the position he’s in. He’s fearless about throwing himself in. I think he was quite inspired by the techniques we were employing to be creative in a way that wasn’t stressful and took him out of “What-have-I-got-to-do-today?”. He reminded me that when he’d done Sergeant Pepper’s they’d done it as another band, not The Beatles, and that allowed them to do it. It all comes back down to having fun, having that child’s mind to what you’re doing.

I really pushed him to do more vocals. That was the challenge, to approach it the way we’ve done before but with songs. He said, “How are we going to do that, come in with a blank sheet every day?” I said, "We’ll use the artists’ approach, Burroughs' cut-up technique, bring in loads of poetry books, pick a line or word from each of these three poems, then we’ll throw them up and see what lines come out. You have to do the vocal in 20 minutes.” He liked that. At the same time I was learning so much from him about how to remain inspired. He’d been doing a symphony one day when he came in, next time I’d see him he’d be doing a poetry book. The next time he’d been doing some painting. I remember asking him if he ever got bored and he said, “Hmmm… no.” He really utilises his time and really appreciates the position he’s in. He’s fearless about throwing himself in. I think he was quite inspired by the techniques we were employing to be creative in a way that wasn’t stressful and took him out of “What-have-I-got-to-do-today?”. He reminded me that when he’d done Sergeant Pepper’s they’d done it as another band, not The Beatles, and that allowed them to do it. It all comes back down to having fun, having that child’s mind to what you’re doing.

Did you work with an Icelandic band called Þeyr [pronounced “Thear”]?

No, that was Jaz. I never went to Iceland.

I thought you’d gone to Iceland…

No, no, I never went, I was the only one who didn’t go. Jaz went on his own [in 1982]. At first the band went, “What do we do?” we had to do TOTP without him. Then we read a letter in the NME that he was starting a band without us, with Icelandic musicians. We started auditioning for another singer and we had Iggy Pop ring up, Bill Drummond. But [Killing Joke guitarist] Geordie had already plotted with Jaz and slipped off one night to Iceland.

I do apologise for getting my facts wrong. I thought you went over to Iceland briefly.

That’s OK, it’s in the darker realms of mythology. That was when I started Brilliant which, initially, would have been a B-side track for Killing Joke. I started Brilliant with [Killing Joke drummer] Paul [Ferguson]. Then Geordie left and there was no point in being Killing Joke. Paul also went off to Iceland and it was very difficult for them. They ended up being beaten up, having to do a runner in the middle of the night, getting out of the country fast. But I think they came back with Þeyr material that Jaz was involved with. There was a very occult agenda at that point for Jaz and Paul.

There seemed to be an obsession with astrology, then, in Killing Joke.

Not just astrology, but Iceland has these geomantic energy lines all connected to Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth and mythology. They were very drawn to go there and it was very important they did go there. They met up with some important people. [Hilmar Örn] Hilmarsson who’s now head of the Icelandic pagan religion, their national religion [Ásatrúarfélagið]. He was one of the guys who was in that band. Others of them became The Sugarcubes as well. Of course Björk was very much involved with them. They had their own Icelandic runic tattoos. Björk’s got one on her arm, a magical Icelandic sigil.

Not just astrology, but Iceland has these geomantic energy lines all connected to Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth and mythology. They were very drawn to go there and it was very important they did go there. They met up with some important people. [Hilmar Örn] Hilmarsson who’s now head of the Icelandic pagan religion, their national religion [Ásatrúarfélagið]. He was one of the guys who was in that band. Others of them became The Sugarcubes as well. Of course Björk was very much involved with them. They had their own Icelandic runic tattoos. Björk’s got one on her arm, a magical Icelandic sigil.

You sidestepped all that and went off on your own journey.

Yeah, not out of choice. I didn’t leave the band, they left me. [Laughs uproariously]

The third Killing Joke album, Revelations, was recorded with Conny Plank?

He produced it, the first producer we’d worked with. He was the only one we could agree on. He was very cool. He came out of that German commune squat scene. He’s also worked with Stockhausen and was obviously very pivotal in the whole kosmische Krautrock scene. We worked with him just after he finished working with D.A.F. so he was a prime architect of the next wave – EBM – a seminal figure for us. We knew his track record inside out. Apart from Kraftwerk and Can he’d done a series of albums on the Sky label with [Dieter] Moebius and [Brian] Eno which we really into. We were on EG records which was the same label as Eno. We were really down with the ambient aesthetic and Plank was a prime mover in that. He’d also produced "Vienna" for Ultravox which had been a massive record. We were really impressed with what he’d done on that. Nevertheless the album isn’t a favourite of mine. It ended up sounding bizarrely conventional. But I’d also just had this massive LSD meltdown on the Kings Road where I infamously burnt money in a kimono while wearing swimming trunks. I wasn’t in a together place, I was in Syd Barret land at that point. That was one of the reasons when Jaz came back from Iceland, knocked on my door and said, “We’ve got this tour of Germany, do you want to do it?” I said, ‘No, get [Paul] Raven.” I felt I needed to take time out from touring and find out who I was. It was a shamanic initiation, that meltdown. I really needed to find my path and that was spending time in the studio and also exploring some more experimental types of music which I could only really do as a producer, with having a label. Very shortly after that I started WAU! Mr Modo with Alex.

The Verve’s “Bittersweet Symphony” sounds to my ears like a producer's record rather than a rock band record. How involved were you in its creation?

Very. I co-produced it with Chris Potter who was our engineer, but the actual track [Verve frontman] Richard [Ashcroft] had written to a loop of the Andrew Loog Oldham Orcherstra’s version of the Stones’ “The Last Time”. Just with his vocal and that loop it was there. I was, like, “Wow, that’s a hit,” but Richard wasn’t so into it at first. He was like, “Don’t do it. I don’t want to hear it.” They’d come out of being a very experimental jamming acid rock band. On the last album prior [A Northern Soul], they’d done one song, “History” that really showed the way forward. When I started their next album [Urban Hymns], the band had split up and it was a Richard Ashcroft solo album. The band were employed as session guys but they were all entirely supportive of what he was trying to do. I did have to track and build up "Bittersweet" when Richard wasn’t there, when he didn’t turn up, because he didn’t want us to work on it. I got it sounding great and I thought, well, I’ll call a playback meeting, get his label, our managers down, play them a few tracks. Often a playback meeting gets a lot of confidence in a session, a validation that you’re doing the right thing. I thought, “If it goes well I’ll drop 'Bittersweet' in at end and he’ll like it". And he did. From that point on he was fully engaged with it.

Very. I co-produced it with Chris Potter who was our engineer, but the actual track [Verve frontman] Richard [Ashcroft] had written to a loop of the Andrew Loog Oldham Orcherstra’s version of the Stones’ “The Last Time”. Just with his vocal and that loop it was there. I was, like, “Wow, that’s a hit,” but Richard wasn’t so into it at first. He was like, “Don’t do it. I don’t want to hear it.” They’d come out of being a very experimental jamming acid rock band. On the last album prior [A Northern Soul], they’d done one song, “History” that really showed the way forward. When I started their next album [Urban Hymns], the band had split up and it was a Richard Ashcroft solo album. The band were employed as session guys but they were all entirely supportive of what he was trying to do. I did have to track and build up "Bittersweet" when Richard wasn’t there, when he didn’t turn up, because he didn’t want us to work on it. I got it sounding great and I thought, well, I’ll call a playback meeting, get his label, our managers down, play them a few tracks. Often a playback meeting gets a lot of confidence in a session, a validation that you’re doing the right thing. I thought, “If it goes well I’ll drop 'Bittersweet' in at end and he’ll like it". And he did. From that point on he was fully engaged with it.

Didn’t the Stones end up making all the money?

What are you talking about? Richard Ashrcoft made millions off it. The Stones only got the publishing money. But, to be fair, if you listen to the melody it’s the same as “The Last Time”. It is. I said to my manager, “I can try and take the sample out.” He said, “It’s not the sample, the melody is the problem.” The sample we used had hardly any strings – it was the groove we were going for. We ended up getting Will Malone to do the arrangement. He’s the one who made the strings so iconic and, of course, we got James Lavelle to do the classic remix of it. It was seeped in post-ecstasy, post-acid house culture. The first rock band to do that properly was Primal Scream with Screamadelica which [Creation Records head honcho] Alan McGee put together. That came together after Weatherall and Alex remixed two tracks. “Bittersweet” is definitely in the same aesthetic as that. Also The Verve and Urban Hymns really fulfilled the artistic promise of Britpop. They came after Britpop, but they were informed by Oasis and what was happening – though Oasis never made an album as good as Urban Hymns or that travelled as far. In that respect, we caught a couple of generations beginning and ending. It did sum up the end of the Nineties.

- PPL is the UK licensing company for recorded music ppluk.com

Add comment