We seek it here, we seek it there, we seek it everywhere - that dance work where you lose consciousness of all the hands behind it and surrender to one focus. In Russell Maliphant’s radiant AfterLight, dance, light, sound all move as one, a distilled 60-minute spell of dark, hushed beauty that touches on disturbing things: on ecstasy, madness, desire, jealousy, resignation to the void, and of course on Vaclav Nijinsky.

Maliphant made a solo last year for Sadler’s Wells on a Diaghilev tribute programme. It whirled like Nijinsky’s paintings from his hospital, where the young dancer retreated all too soon from his glittering stage career, and Charlotte MacMillan took some rapt photographs that glimpsed how it pinpointed the experience of isolation, utterly lonely and still inspiring. This solo has now been enriched by extension and development into a three-part piece deriving from Nijinsky’s L’après-midi d’un faune of a century ago, but bathed in some inexplicable new marvel of technical light projection to create a truly magical little passage of theatrical time.

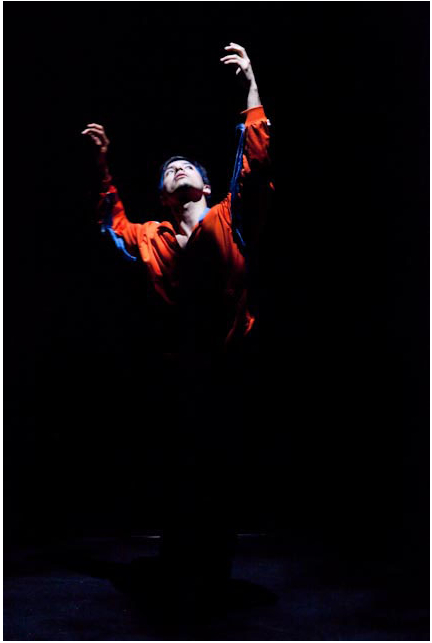

The remarkable Daniel Proietto seems to channel Nijinsky's youth and ardour, a boy off the street wearing red jacket and white hat, the colours reminiscent of the puppet Petrushka (one of Nijinsky’s signature roles). He is banged up in the dark, he arcs backwards and up into the emptiness, turning and turning while the ground beneath him seems to spin, transformed into clouds, space and waves of light by the genius of Michael Hulls and his team. The spare piano notes of EriK Satie’s Gnossiennes wind musingly through the silence (Dustin Gledhill’s recording), and one’s mind is caught up and held in quiet existential questions.

The remarkable Daniel Proietto seems to channel Nijinsky's youth and ardour, a boy off the street wearing red jacket and white hat, the colours reminiscent of the puppet Petrushka (one of Nijinsky’s signature roles). He is banged up in the dark, he arcs backwards and up into the emptiness, turning and turning while the ground beneath him seems to spin, transformed into clouds, space and waves of light by the genius of Michael Hulls and his team. The spare piano notes of EriK Satie’s Gnossiennes wind musingly through the silence (Dustin Gledhill’s recording), and one’s mind is caught up and held in quiet existential questions.

When he takes off his bomber jacket, he sheds thousands of years and is suddenly a bare-chested youth, nakedly open to the elements, spinning along a long diagonal as if pirouetting on clouds, half-seen in the dappling light, which splotches his body with the same piebald stains of Nijinsky’s Faun costume. This cunningly transmits us to a dreamy section where two girls in short, archaic white tunics and bare feet lazily frolic on the ground as if talking about their lovers. The echoes of L’après-midi d’un faune become more intense now.

The faun arrives. The two nymphs appear to recognise him in their dream and woozily play for him, their bodies as soft and easy as snakes, while the Satie notes are transformed by Andy Cowton, the aural wizard here, into a fabulous nocturnal soundscape with hints of remote gamelans, misty percussive rattles and even owl hoots. It’s potently atmospheric and Maliphant's choreography whispers with an extraordinary clarity. Not athletic, as in Broken Fall (Maliphant’s cliff-hanging trio for Sylvie Guillem and the Ballet Boyz), not tensely masculine (as in his duet Critical Mass), but alluring and earthy, all the echoes of ballet in Maliphant’s background banished, just the associations of ballet history left hanging.

To an oriental plucked instrument (possibly a dulcimer?) there is an encounter between the faun and one nymph, a delicate introductory dance, while Hulls sweeps atmospherics and clouds before and behind them with his wizard box of tricks. I have never before felt a front gauze so unobtrusive, so imperceptible - it is a curtain of air, merely, upon which Hulls paints. The two girls (Silvina Cortes, Olga Cobos, both densely sensual) have a competitive stand-off that has shades of the tennis game in Jeux, another Nijinsky vehicle, but is equally a lightly brushed insight into two women attracted to the same thing.

The entire thing is as fleeting and elusive as thought, but it is a draught of the purest essence of dance. Delicious, bittersweet, puzzling, this is an experience I feel I could become addicted to. It’s finished at Sadler’s Wells for now, but must certainly be destined for touring, and it’s worth going miles to see. Credits to Es Devlin, concept designer, Stevie Stewart for the costumes, and Jan Urbanowski and James Chorley, cooking up the graphical images. It's a pleasure to see what a large team was involved in producing such a singular focus. Diaghilev, to whom all of this is an indirect tribute, would have surely been properly astonished.

Add comment