theartsdesk in Moscow: The Sovremennik Theatre Visits London | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Moscow: The Sovremennik Theatre Visits London

theartsdesk in Moscow: The Sovremennik Theatre Visits London

Chekhov from the horse's mouth as Russia's flagship theatre company shows how

Twenty-odd years ago, on the eve of the break-up of the Soviet Union, the country’s cultural world was anticipating cardinal changes – anything from a series of closures to a radical alteration in which the way art would be produced under new economic circumstances. Nowhere more perhaps than in theatre, where the established universal nationwide system of repertory companies faced potential implosion.

Despite a subsequent decade of considerable uncertainty, such fears would prove largely unfounded. This month’s visit by Moscow’s Sovremennik Theatre to London offers a chance to see the very best of a Russian repertory company with two remarkable productions of Chekhov, while the gulag drama Into the Whirlwind hits audiences as viscerally today as at its premiere back in 1989.

Quite how strongly the Russian theatre world differs from its UK counterpart is something that British theatregoers may initially struggle to appreciate. London, with its flagship National Theatre and independent, rotating West End productions (including those originating from the National), couldn’t be further away from Moscow, where the main city theatres almost completely still operate on a repertory system: actors often join their companies directly at graduation from theatre schools and can remain with them for decades, in some cases whole lifetimes.

Successful productions may well remain in a venue’s repertoire for similar lengths of time, periodically reworked, with the introduction of new cast over the years. The system isn’t set in stone, though, as one theatre may borrow a star from another for a particular production, and now in parallel, albeit still on a small scale, independent producers are slowly developing an “enterprise” system, as it’s known in Russian, which would look much more recognisable to West End producers.

At its best, as at the Sovremennik (the theatre's name translates as “the contemporary”), that often means rehearsal periods of a length only to be envied elsewhere in the world, actors of national renown developing roles over years, even if they play them only a handful of times every month.

Jjuggling schedules, especially for those in parallel demand for film work, can prove tricky. (It proved even trickier with leading Sovremennik actress Marina Neelova, who plays the lead in Into the Whirlwind as well as Ranevskaya in The Cherry Orchard, in the London productions: her diplomat husband was posted to Paris in the 1990s, and Neelova would fly back to Moscow for several days every month so as not to lose contact with her company.)

Clearly there are potential downsides for such a system, too, where stagnation sets in, and theatres seem to run on inertia rather than on fresh energy; the character of the theatre’s artistic director also plays a significant part, directing the company either towards innovation, entrenched academic grandeur, or prioritising entertainment, with such questions depending as much on personality as on artistic direction. The tenures of some of these leaders – not unlike African despots - end as often as not only with their deaths, with the subsequent health of their companies depending not least on how much they have invited other younger figures in to work with the troupe and refresh the general artistic atmosphere.

Galina Volchek (pictured right) has been the undisputed “face” of the Sovremennik for nearly four decades, since she assumed the role of artistic director back in 1972 (she had been a founding member of the theatre at its creation in 1956, initially distinguished as an actress). She took on that leadership against what seemed strong odds – she was a woman (leaders of the Soviet cultural world were with very rare exceptions men), not of Russian ethnic origin (her family was Jewish), and in those years, most unusually, not a card-carrying member of the Communist Party (Volchek refused many subsequent invitations to join).

Galina Volchek (pictured right) has been the undisputed “face” of the Sovremennik for nearly four decades, since she assumed the role of artistic director back in 1972 (she had been a founding member of the theatre at its creation in 1956, initially distinguished as an actress). She took on that leadership against what seemed strong odds – she was a woman (leaders of the Soviet cultural world were with very rare exceptions men), not of Russian ethnic origin (her family was Jewish), and in those years, most unusually, not a card-carrying member of the Communist Party (Volchek refused many subsequent invitations to join).

Such historical details are of more than academic interest today, just as the story of the founding of the Sovremmenik itself 55 years ago speaks much about what it went on to become.

It emerged from an informal group of students graduating from the school of the Moscow Arts Theatre (the legendary creation of Konstantin Stanislavsky so closely associated with Anton Chekhov), who rebelled against the prevailing deadness of Soviet theatre, and in the circumstances of the cultural “thaw” that followed the death of Stalin, were allowed to do so. It was a group that was founded by its members rather than from “above”, by the authorities; it pursued stories and approaches that brought everyday problems and approaches to psychology in plays from contemporary writers - in short, it had a style that spoke very strongly and distinctly in the 1960s.

Its internal unity was most challenged in 1970 when the founding artistic director, Oleg Yefremov, took up the reins at the Moscow Arts Theatre, taking many of the Sovremennik’s troupe with him, and proposing that the two theatres merge. Volchek was elected as artistic director two years later, after an uneasy interim when decisions were taken on a fully collective basis, and in 1974 the theatre received the elegant classical building, a former cinema, on one side of Moscow’s Clean Ponds that remains its home today.

Conflict with censors were frequent, as each new production would only be passed after any number of viewings and subsequent requested modifications; on occasion, permission could be refused altogether (as well as the Sovremennik, Yury Lyubimov's Taganka Theatre was the other most "unofficial" such structure, culminating in that director being stripped of his Soviet citizenship in 1984 and exiled).

Volchek has written of the shock of the final preparations for the premiere of Into the Whirlwind in 1989: “I will never forget when at the submission of [that play] I arrived, sat down in the auditorium and waited for somebody to arrive. I was asked, ‘Why don’t you let the group begin the show?’ And it was only then that I realised that they – the makers of destinies [the Glavlit, or special censorship committee] - would no longer be coming. I hope not coming to anybody ever again!”

Into the Whirlwind is an adaptation of the memoirs of Yevgenia Ginzburg (published in Russia under the title The Harsh Road) telling of the story of her immersion into the hell of the Stalinist gulag. A convinced Communist, Ginzburg was a journalist and successful academic at Kazan University in the 1930s, happily married to a senior party official and with children (one of whom became the future Soviet writer, later exiled, Vasily Aksenov), until her arrest and sentence in 1937 on charges of being a counter-revolutionary. Despite protesting her innocence and continuing party loyalty against determined interrogation, she was sentenced to the labour camps after a symbolic court-hearing lasting six minutes, which would see her, still a believer in Communism, spend the next 18 years in prison and camp environments, predominantly in Kolyma in the Soviet Far East.

Released and rehabilitated in 1955, Ginzburg finished her memoirs in 1967, which were subsequently published abroad. Volchek read them in the 1970s: “I read the book fervently, I could not stop. My heart pained – not in the figurative sense, but literally. As a director I could not do anything with the text at the time – it was not even worth thinking about. And so I placed this most intense emotion, this text, into some distant corner of the mind, which you accesss not every day, but only in difficult and critical moments.”

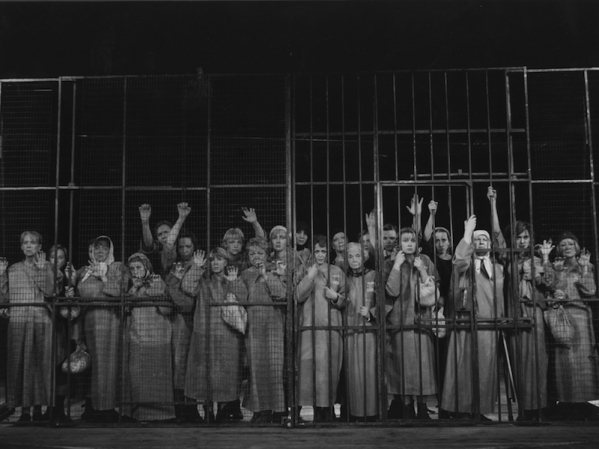

Some of its scenes, as when female prisoners approach the front of the stage (pictured above) to confront the audience from behind bars, are among the most powerful theatrical images that I remember. Neelova is almost incandescent playing Ginzburg, one of Communism’s faithful plunged into a hideous world of interrogators and other women, from simple people to criminals, subversives and the international detritus of World War II and associated ideological conflicts. It’s above all an ensemble piece, with a cast of around 60, and heavy in a purely scenic sense (Volchek can be as demanding in the sheer technical possibilities of theatrical staging as she is from her actors).

If until perestroika the Sovremennik was forbidden from touring to the West, the new era – “the joy of my generation is in the fact that we, after fully experiencing the nightmares and insanity of the later socialism, were able to see another, ever-changing life,” as Volchek remembers – saw it perform around the world, with Whirlwind its pièce-de-résistance. More than 20 years on, it still plays to full houses in Moscow, especially gratifying for the director. She sees the play as “primarily a warning” to future generations: “I think this play will serve as an inoculation for them. It is not just about the fact that the human ‘I’ can be defended in any situation, but also about the fact that you cannot allow yourself to humiliate another human being – be it in Stalinist camps or, and I intentionally refer to a diametrically opposite example, in a metro carriage.”

In Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard (pictured above, with Marina Neelova as Ranevskaya, front), Volchek sees a conflict between generations which ends with an old order being despatched to history, while a new order arrives – itself very relevant at the time of its 1997 premiere. It was the third time that the director had staged the play at the Sovremennik, with a cast that shows off the theatre’s senior generation of actors at its very best.

They are names familiar to the great majority of the Russian population over a certain age: stage and cinema star power in the Soviet era was proportionately higher than today, given a lack of interest in politics and the absence of the kind of glamour pop generation that has appeared – with a vengeance - in the new Russia.

Names like Igor Kvash (another co-founder of the theatre back in 1956) as Gaev and Sergei Garmash as Lopakhin may be better known today from their screen and television roles, but it’s a simple delight here to watch such professionals playing in ensemble with one another, still developing the nuances of their characters after more than a decade playing the roles.

In The Three Sisters it’s the younger generation of actors who reveal themselves, none more so than Chulpan Khamatova as middle sister Masha, dressed in black (main picture, top). The kind of attention to detail that marks great productions of Chekhov is to be found in both productions in spades; Volchek somewhat regrets that the London performances are accompanied by surtitles rather than earphone translation, potentially drawing the viewer’s attention away from the stage image itself - so bear that in mind.

“I relate to Chekhov not from a distance,” the director has said. ”With piety, but without pomp and internal trepidation – he is alive, current and contemporary.” To find a sense of the new that is nevertheless anchored in the past is a search that somewhat defines the Sovremennik itself, adapting from its Soviet-era position to the radically different society that followed and surrounds it today (the fact that its London tour is supported by Roman Abramovich somehow speaks for itself). Its future surely seems assured even beyond Volchek’s stewardship, as long as it keeps up just her dedicated process of exploration.

- The Sovremennik Theatre performs at London's Noel Coward Theatre 21-29 January

- Find Yevgenia Ginzburg's Into the Whirlwind on Amazon

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Intimate Apparel, Donmar Warehouse review - stirring story of Black survival in 1905 New York

An early Lynn Nottage work gets a superb cast and production

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Hercules, Theatre Royal Drury Lane review - new Disney stage musical is no 'Lion King'

Big West End crowdpleaser lacks punch and poignancy with join-the-dots plotting and cookie-cutter characters

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

Showmanism, Hampstead Theatre review - lip-synced investigation of words, theatricality and performance

Technically accomplished production with Dickie Beau never settles into a coherent whole

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

4.48 Psychosis, Royal Court review - powerful but déjà vu

Sarah Kane’s groundbreaking play gets a nostalgic anniversary reboot

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Joyceana around Bloomsday, Dublin review - flawless adaptations of great dramatic writing

Chapters and scenes from 'Ulysses', 'Dubliners' and a children’s story vividly done

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

Stereophonic, Duke of York's Theatre review - rich slice of creative life delivered by a 1970s rock band

David Adjmi's clever and compelling hit play gets a crack London cast

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

North by Northwest, Alexandra Palace review - Hitchcock adaptation fails to fly

Emma Rice's storytelling at fault in misconceived production

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

Hamlet Hail to the Thief, RSC, Stratford review - Radiohead mark the Bard's card

An innovative take on a familiar play succeeds far more often than it fails

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

The King of Pangea, King's Head Theatre review - grief and hope, but no connection

Heart and soul proves insufficient in world premiere of therapeutic show

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

Add comment