Two Boys, English National Opera | reviews, news & interviews

Two Boys, English National Opera

Two Boys, English National Opera

Nico Muhly's first opera is a thrilling addition to the repertoire

Saturday, 25 June 2011

Nicky Spence's Brian surrounded by a chorus of online chatterers: 'One breathtaking scene saw screen-saver geometry explode like fireworks over a veiled chorus of online chatterers, intermittently illuminating them and their computers'All images Richard Hubert Smith

Nico Muhly had one humble aim for his first opera. He wanted to create an episode of Prime Suspect, he told me last week. "A grand opera that functions as a good night's entertainment." There's no doubt he's achieved that. Two Boys, receiving its world premiere last night at the English National Opera, is as gripping an operatic thriller as any ever penned.

But is there more to the work than that?

The opera tackles the great themes of our age: the internet, youth corruptibility, sexual coming of age. And while Muhly's music deals with these with a humanity and wisdom that opens many more emotional and intellectual doors than Prime Suspect could, its most basic building blocks are those of a well-structured ITV crime drama. The plot centres on a real-life attempted murder case. One suicidal teenage internet-obsessive conjures up a fantasy world and persuades another to meet him and to kill him. The opera follows detective Anne (Susan Bickley) as she tries to figure out who did what to whom.

That many of us knew most of the ins and outs of this bizarre story and yet still were hooked to every twist and turn shows the quality of much of screenwriter Craig Lucas's plotting and Muhly's musical setting. For make no mistake, Muhly's score absolutely lives up to the media hype. Neither evading nor aping its Minimalist roots (there are carefully chosen quotes from teacher Philip Glass rather than heavy fingerprints), the score sets out on its own distinct, economical but powerful path.

Forbidding dark oceans of sound (punctuated by great booming eruptions from timpani or tuba) orbit the story like journeying whales, conjuring up the bottomless vastness of the internet, and echoing the sounds of the sea in Grimes. These give way to shallower pools of sound that allow for the music to move at a faster pace and engage in the more frenetic online activity, not least a bit of masturbation. This dramatic shape-shifting, mirrored by Lucas's energetic plotting which ping-pongs back and forth in time, is aided by a remarkably fluid (if a little drab and bitty) set from Michael Yeargan.

It's remarkable how the production and story conjure up this feeling of discombobulation without leaving you completely adrift. The glue is no doubt in the music: both in its recurring patterns and forms and its melody. Muhly writes quite beautifully for the voice. And every singer repays him handsomely. Heather Shipp and her glassy tones were mesmerising in the service of the mysterious internet intercessor Fiona. Mary Bevan was strong as the horny schoolgirl Rebecca. Jonathan McGovern delivered some exceptional singing as Jake.

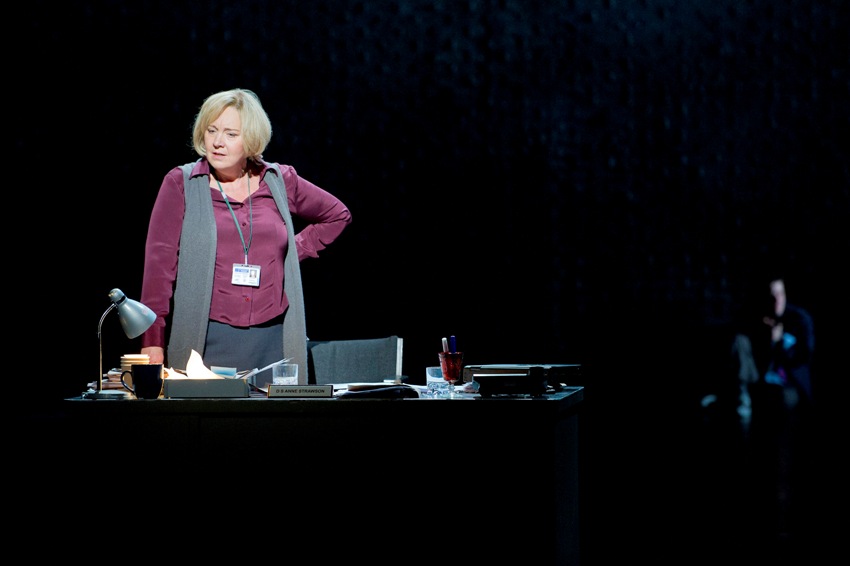

What was especially fine about the central triumvirate, however, was the acting. Susan Bickley's Detective, Anne (pictured), was like watching vintage Helen Mirren. Nicky Spence (Brian) may not have been a believable teenager to look at but more than made up for that in his irascible delivery. And then there was sweet little Joseph Beesley, the heartbreakingly damaged schoolboy mastermind of all this madness. His negotiation of the vocal and emotional terrain was simply incredible.

What was especially fine about the central triumvirate, however, was the acting. Susan Bickley's Detective, Anne (pictured), was like watching vintage Helen Mirren. Nicky Spence (Brian) may not have been a believable teenager to look at but more than made up for that in his irascible delivery. And then there was sweet little Joseph Beesley, the heartbreakingly damaged schoolboy mastermind of all this madness. His negotiation of the vocal and emotional terrain was simply incredible.Muhly's entry to the genre proves beyond doubt that he is a composer to be reckoned with. Stealing the show, however, and somewhat overshadowing the prosaics of Bartlett Sher's production and direction (a good effort but uninspirational) were the graphics from Fifty Nine Productions and the way they worked their projections out over the choral writing. One breathtaking scene saw screen-saver geometry explode like fireworks over a veiled chorus of online chatterers, intermittently illuminating them and their computers. Their unsynchronised psalmody (in chatroom speak) resembled the ravishingly ragged feel of a Russian Orthodox congregation.

Muhly's writing was full of powerfully resonant moments like these, which seemed to bore straight to an emotional core. I loved all the writing for massed voices. I loved the way he refused to end each part on a full stop. I loved the tuba-menaced quintet of the end of the first act. The heart stopped in the final passacaglia. Was there too much explanation of what the opera was about? No doubt. There were problems with the libretto (a number of weak lines here and there). But overall this was a terrific evening of opera. Muhly's first entry to this genre - a long overdue operatic assessment of one of the great game-changers of our times: the Manichaean reality that is the internet - proves beyond doubt that he is a composer to be reckoned with. Do we have an heir to John Adams? Very possibly.

These give way to shallower pools of sound that allow for the music to engage in the more frenetic online activity, not least a bit of masturbation

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

Tosca, Welsh National Opera review - a great company reduced to brilliance

The old warhorse made special by the basics

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: The Marriage of Figaro, Glyndebourne Festival review - merriment and menace

Strong Proms transfer for a robust and affecting show

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

BBC Proms: Suor Angelica, LSO, Pappano review - earthly passion, heavenly grief

A Sister to remember blesses Puccini's convent tragedy

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

Orpheus and Eurydice, Opera Queensland/SCO, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - dazzling, but distracting

Eye-popping acrobatics don’t always assist in Gluck’s quest for operatic truth

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

MARS, Irish National Opera review - silly space oddity with fun stretches

Cast, orchestra and production give Jennifer Walshe’s bold collage their all

Add comment